Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The 'serious games' phenomenon isn't just about education - it's about tackling major social issues and making players reconsider their opinions through games - and Gamasutra talks to Paolo Pedercini, Chris Swain, Ian Bogost, and Gonzalo Frasca about activist gaming today.

Think back to when you first contemplated getting into the video games industry. The ‘aha’ moment probably occurred while playing a particular game.

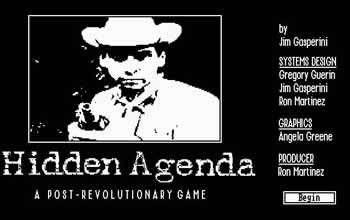

That certainly was the case for Suzanne Seggerman, co-founder and president of Games for Change, the social change/social issues branch of the Washington, D.C.-based Serious Games Initiative. While working as a documentary film producer for PBS, a co-worker slipped Seggerman a diskette containing Jim Gasperini’s government simulation game, Hidden Agenda. “I had played a little Asteroids while in college,” the New Yorker remembers, “but I definitely wasn’t a gamer.”

That all changed after she spent a weekend with her computerized present. “It was a transformative experience for me,” Seggerman says. “I sat up in the attic while a party was going on below—and I’m never one to miss a good party—and must have played the game for 10 hours straight.”

“I learned more about politics by playing Hidden Agenda than by reading 10 newspapers,” she adds.

Seggerman continued making films for a few years, but that ‘aha’ moment was never far from her thoughts. “I made a mental note that it had been something important and powerful and that I’d get back to that place at some point in my career,” she says.

That moment came in 2004 when Seggerman, who in the meantime had earned a master’s degree from New York University's Interactive Telecommunications Program, co-founded Games for Change with Global Kids’ Barry Joseph and NetAid’s Ben Stokes (now with the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation).

That moment came in 2004 when Seggerman, who in the meantime had earned a master’s degree from New York University's Interactive Telecommunications Program, co-founded Games for Change with Global Kids’ Barry Joseph and NetAid’s Ben Stokes (now with the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation).

“We act as the primary community of practice for the people making activist games, documentary games, persuasive games, political games, serious games, social-issue games—whatever you want to call them,” Seggerman explains.

Games for Change fills a void Seggerman discovered when she attended her first Game Developers Conference in 1996. “I went there to find people working on what I called ‘meaningful’ games,” she says. “Much to my surprise, I couldn’t find anyone.”

“That made me realize what an aberration Hidden Agenda was at that point,” Seggerman adds. “I’m amazed it made it into my hands when it did, because I don’t think any other game would have impacted me the way that one did.”

Serious Attention

Serious games are no longer an aberration, of course. Countless examples created by the likes of Ian Bogost, Gonzalo Frasca, Paolo Pedercini, Chris Swain and more have caught the attention of the press and the public in the years since Seggerman’s first trip to GDC. They’ve also caught the attention of the mainstream game development community, though not often in a positive way.

“There’s a lot of hatred toward serious games right now,” Seggerman says, adding that the lack of love could be due to any number of reasons. “It could be because of the name or it could be because they think—and rightfully so—that many educational games have been terrible,” she adds. “Bad educational software has done us a lot of harm.”

Another knock against so-called serious games is that they simply don’t stack up to more mainstream offerings.

“Most people are less generous with their words; they’d say that most activist/political/serious games just plain suck” says Bogost, Ph.D., founding partner of Atlanta-based Persuasive Games, LLC, makers of Presidential Pong, Disaffected! and Airport Insecurity. “And that might be true, in part. The level of craft in serious games often leaves much to be desired.”

Powerful Robot Games' September 12th

Powerful Robot Games' September 12th

Of course, mainstream titles generally garner bigger budgets than their “serious” brethren. "I think the main problem is that it is very expensive to make any kind of game," offers Frasca, co-founder of Powerful Robot Games, a Uruguay-based studio that has crafted such titles as September 12th and the Howard Dean for Iowa Game. “Political games generally do not have a financial return, and that makes it particularly hard to produce them with the same quality as commercial work.”

Swain, an assistant professor in the USC School of Cinematic Arts’ Interactive Media Division and a co-director of the school’s Electronic Arts Game Innovation Lab, also cites miniscule budgets and less access to experienced talent as reasons for the discrepancy between mainstream and serious games.

That said, Swain—who designed The Redistricting Game and acted as a faculty advisor for the PlayStation3 game, fl0w—suggests “the field of political/activist games is very young. We need some success stories to prove our value because right now political games mostly grab headlines and have little real impact.”

Pushing Forward

Swain hopes The Redistricting Game, which launched at the recent Games for Change Festival in New York, is one of the success stories that helps push the genre forward.

Such a notion may seem a bit pie in the sky, especially considering The Redistricting Game’s content. According to a press release that preceded the game’s launch, “the game exposes how redistricting works, how it is abused and how it adversely affects democracy. It provides hands-on understanding of the real redistricting process, including drawing district maps and interacting with party bosses, congresspeople, citizen groups and courts. Players directly experience how crafty manipulations of lines can yield skewed victories for either party—effectively allowing politicians to choose their voters instead of voters choosing their politicians.”

Why did Swain make a game about gerrymandering, and why would anyone want to play it? Telling someone how redistricting works and what it means can be cumbersome and hard to grasp, Swain replies. “However, if she could gain an understanding of redistricting by experiencing it via a fact-based interactive system, then she may come to her own conclusions about its ramifications.

“Our goal with The Redistricting Game is to provide an objective look at the phenomenon and let people come to their own conclusions,” he adds. “We don’t side with one political party and we don’t push an agenda. We just want the game to demystify redistricting in a credible way and we want people to have a good time while playing it.”

Another game that hopes to demystify complex issues, impact society and promote change is PeaceMaker, released by Pittsburgh-based ImpactGames in 2006. Started by Eric Brown and Asi Burak while they were students at Carnegie Mellon University, PeaceMaker allows users to play the part of an Israeli prime minister or a Palestinian president and make diplomatic, security and economic decisions for their virtual country of choice.

Although Brown and Burak hoped their game would make an impression on the general public, they also hoped it would influence their peers in the mainstream game development community. “We really wanted to drive the industry,” says Brown, the founder and former co-manager of Issue Design Build in Seattle. “We wanted to make something that compares to the role documentaries play in the movie industry.”

“The demographic of gamers historically is 12- to 18-year-old boys,” he adds, “which has grown as that generation got older. In our minds, there is a group within that community that is interested in something with a bit more meaning, a little more depth. We wanted to show them you can produce a game that is just as engaging as anything out there, but also has a positive message and influence.”

Brown says he and Burak chose to make a video game about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict because “games are really good at putting people in the shoes of someone else—something you can’t always do with something like a news article. Games can empower people to interact with an environment, and they can contextualize events in time.”

Seggerman agrees. “Games can help people put themselves in perspectives otherwise unavailable to them. They can let people exhibit behaviors or try roles they’ve never tried before.”

Likewise, she says, “games are fantastic at allowing players to explore complex, interrelated issues and fiddle with those issues to see how they affect each other.” Global conflicts and even environmental issues are especially worthwhile topics for serious games, Seggerman adds, “because you can’t really look at one aspect of global warming, for instance, without looking at a myriad of other aspects.”

Alternative Topics

Headline-grabbing subjects like global warming or third-world poverty (as seen in the popular Ayiti: The Cost of Life) aren’t the only ones tackled in serious games. Some of the genre’s most captivating offerings take on topics that are a bit further from the limelight.

Take Persuasive Games’ Disaffected!, which puts players “in the role of employees forced to service customers under the particular incompetences common to a Kinko’s store.” Bogost says he made the game because “Kinko’s is a place I both frequent and abhor and I felt that a satire of it had the opportunity to speak to a whole range of people.”

“Getting crappy service at Kinko’s is a mundane, everyday experience that all of us have had,” he adds. “Why does it happen? We don’t answer that question in the game, but we offer players the chance to step behind the counter and imagine what forces might be driving these dissatisfied workers. Is it simple incompetence? Sedition? Labor issues?”

Similar questions are addressed in another of Persuasive Games’ offerings: Airport Insecurity. “It’s another everyday experience that I hoped players could start to ask questions about,” Bogost says. “I’m really much more interested in the mundane than the serious. It’s just that our work often breaks a lot of unspoken rules about what can be represented in a video game.”

The same can be said for the products of the Italian video game collective La Molleindustria, headed up by Paolo Pedercini. One of studio’s best-known releases is The McDonald’s Video Game, which puts players behind the counter (and into the back office) of the world’s most famous (and infamous) fast-food chain. The lesser-known Tamatipico, on the other hand, focuses on the often-ignored world of flexworkers, while another La Molleindustria offering, Queer Power: Welcome to Queerland, turns a curious eye toward “queer theory.”

“I see a lot of cartoons and movies that deal with gender issues, but video games too often spread homophobic messages,” Pedercini says of the thought process behind Queer Power, which inverts the fighting game archetypes created by arcade-style beat ‘em ups like Capcom’s seminal Street Fighter II.

“Game conventions are strongly biased by cultural and ideological values,” the developer says. Overturning those clichés “is a way to play with players’ expectations and push them to reflect on the stereotypes in commercial games.”

Offering gamers “alternative points of view” is a goal Pedercini and his crew set for each of La Molleindustria’s releases. “We believe that if we want to have an impact on society we must influence mainstream pop culture,” Pedercini says. “The progressive forces always ignore the importance of pop culture in the opinion-making process.” Conservatives, he adds, have the practice down pat. “Just look at TV shows like Dallas.”

Who Needs Fun?

Play a few rounds of Queer Power and you’ll quickly realize that “having fun” isn’t the point. Nor is it the point of any of Pedercini’s games, it seems. "Fun is never our main

goal-or, at least, not the common concept of fun," he says.

Other developers of serious games share Pedercini’s opinion that video games don’t have to be fun to be worthwhile. “I’m all for escapism,” Frasca says, “but I think that games that deal with serious topics can be more engaging to certain people.”

“For 30 years now we’ve focused on making games produce fun,” adds Bogost. “Isn’t it about time we started working toward other kinds of emotional responses?”

Bogost believes that will happen eventually. “I know that comparisons to the film industry have grown tired and overused,” he says, “but indulge me in this one: When you watch the Academy Awards this year, how many films in the running for awards are about big explosions and other forms of immediate gratification, and how many are about the more complex subtleties of human experience?

“Someday, hopefully someday soon, we'll look back at video games and laugh at how unsophisticated we are today,” Bogost adds. “It's like going to the cineplex and every screen is showing a Michael Bay flick.”

Seggerman offers up a similar comparison to the movie industry when forecasting the future of the serious games movement. “It took a while for film to start taking a look at serious issues,” she says. “We didn’t see documentaries come to the fore until the late 60s or early 70s. So it’s going to be a little while before serious games hit their stride and gain mainstream attention.

“It will get there,” Seggerman adds. “It has to—it’s such a natural fit.”

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like