Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Is it enough if we just improve our game designs for the next-generation, or do we need a new design dictionary?

Thanks to the next-gen hardware of all kinds, we will change the way we design games. Not necessarily because we will want to, but simply because we will have to.

All thanks to a little devil I call sim-toy dissonance.

Imagine a song you love. The better the sound system you listen to the song on, the more pleasure you can get from listening to the song. Suddenly the song opens up, the bass is meatier, and you can hear the extra instruments or every word of the lyrics. It’s still the same song, but better.

When you can hear it exactly the way its creator heard it, it’s a sonic nirvana.

Yeah, not so much with games.

When the game mechanics (the song) stay the same, but everything else - audio, visuals, story-telling, etc. (the fidelity of the song) - gets better, the game suffers.

I call it the sim-toy dissonance. BECAUSE I CAN.

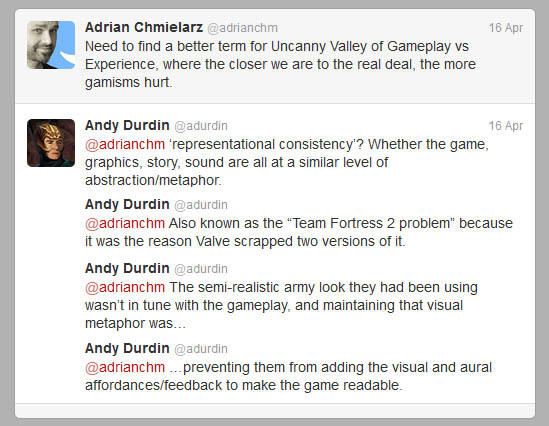

(Not that there cannot be a better term. I did ask around:)

I have finished two big games lately: Bioshock Infinite and Tomb Raider. I was surprised how much I was bothered by the gaminess aspect of these games. From that perspective, Tomb Raider was a much better experience, but still, it was not free of the gaminess pollution.

“Really, Lara? Ammo packs in old, forgotten temples don’t weird you out?”

“Really, Lara? Your skin turns bullet-proof when you’re executing finishers on barely alive enemies?”

“Really, Lara? Setting things on fire annihilates them in a manner of second?”

I enjoyed the game a lot, and to me it’s the best game of this year’s first quarter – but the gaminess did bother me a little.

I just blamed it on the fact I’ve recently got a brain rewiring, and that I cannot disable the game designer mode when I play the games of others – and I moved on.

But then a friend recommended that I played LEGO: Lord of the Rings.

I wasn’t quite sure about the idea, but he promised me it looked incredible in 3D, so I went for it.

Yes, it does look glorious in 3D, but I’ve noticed two much more important things:

1. The game is gamey like hell.

2. The game is deeply fun, engaging, immersive.

Not only I could not care less that the game was gamey, I have embraced it. I was both immersed and engaged, but I also giggled bringing plants to life with my magic little shovel, and felt immense pleasure smashing shit and collecting coins.

Let me run this by you again. I felt pleasure collecting coins. As you maybe know, I hate collecting coins.

I assume my “sim-toy dissonance” becomes clearer now. The more the game is a toy, the more we enjoy its gaminess. The more the game is a sim, the less we enjoy its gaminess.

I keep throwing “sim”, “toy”, “gamey” and “gaminess” around. What the hell?

I assume that the ultimate form of action-adventure gaming is a perfect VR simulation. Like in Matrix, just, you know, not evil. This is what I call a “sim”. We plug ourselves into a device, and other than the fact we know it’s all not real, it all feels real, like we’re living a different, more exciting life.

The "toy" is the opposite of that: an old school game that no element of which can be confused with a VR simulation, neither in gameplay nor in presentation. Toy is to sim what Rubik's Cube is to Matrix.

But hey, Matrix is not going to happen anyway for a long, long time, right?

So until that happens, we need metaphors. Every form of art uses its own set of metaphors, and gaming is no different.

For example, a death in a video game is a game metaphor for a setback. The crosshair in the middle of the screen is a game metaphor for a gunsight. Screen going red is a game metaphor for being wounded.

We use game metaphors to translate life to the language of video games. This is such a vast topic, that one more time let me say that on this here blog I am focusing exclusively on single player action-adventures, the point of which is an escapist experience of adventuring in a different reality.

Now, game metaphors can be a little bit abstract (stamina meter in games is a pretty good metaphor for a real life stamina), or heavily abstract (regenerating health in a video game can be considered a symbol of courage, hope, drive or willpower).

So by “gamey” or “gaminess” I mean game metaphors that are the result of turning life into a video game. Note that this is not exactly the same thing as game mechanics. Not having to take a leak every now and then in a shooter is not game mechanics, it’s a game metaphor for a more exciting, less cumbersome life. So game mechanics are actually just a part of the dictionary we use when translating life to a game.

With this in mind, the full description of the sim-toy dissonance is: the more abstract the game metaphors get while the rest of the game goes towards trying to be a perfect sim, the less we enjoy the experience.

And in human language?

You want your game to be full of mad happy gaminess? Make sure that it’s all cohesively abstract or anti-sim. Make your heroes out of Lego blocks (e.g. Lego game series). Use a visual style that resembles a painting (e.g. Braid, Bastion). Go for the pixel art (e.g. Kentucky Route Zero).

But if you want people to buy into your next-gen high-fi action adventure? Unless you have a darned good, plausible explanation for them, drop weapon wheels, regenerating health, and the audio logs. Because no, people don’t record their most intimate moments on thirty identical voice recorders and drop them in random places. That game metaphor of discovery and knowledge is too abstract.

Old game metaphors are dying, and we’re in a desperate need of a new dictionary.

By the end of this generation, people started to notice the sim-toy dissonance. Is Nathan Drake a mass murderer? Why is no one else but me using Vigors in Columbia? How come that Serra fell, when just one squad of Gears is able to kill thousands of Locust?

We woke the public up with our mo-capped facial animations, pixel shaders and characters they care about. The public will not go back to sleep. The power of the next-generation of both software and hardware tech combined with the crazy skills of the best studios will not allow that to happen.

And if we don’t come through with new or at least heavily improved set of game metaphors, our next-gen extravaganzas will be like that rock song that sounded great in a bar, but when we bought it and played it on our home hi-fi, it turned out that the lyrics are as silly as Justin Bieber talking about Anne Frank.

It’s time.

And it’s going to be very, very hard. Before we figure this out, we’re going to live in a world of pain and misery. We won’t really know what to do just as it took movies some time to figure out what to do with the sound.

But it will happen, and it has to happen. With the next-gen, our games are only going to get better – with better writing, better visuals, better audio – and continue their journey towards being a perfect sim, blurring the line between gameplay and narrative. If our game designs do not follow, our games will suffer.

The next-generation of game design. Whether we like it or not, it is coming.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like