Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Veteran game dev Terry Cavanagh (VVVVVV, Super Hexagon) opens up about the design process of his latest game, Dicey Dungeons, and explains how he created and playtested a specific class: the Witch.

From Megacrit’s Slay the Spire to Peter Whalen’s Dream Quest, deck-building has introduced a new layer of strategic compulsion to the dungeon crawler.

As Slay the Spire’s breakout success has proved, these games’ appeal lies in the way they balance chance and planning, and in the tight relationship between the way your build comes together over a run and the intense tactical decision-making that plays out during each turn.

VVVVVV and Super Hexagon creator Terry Cavanagh has introduced a fresh new take on the genre with Dicey Dungeons, originally a browser-based game (though it's now on Steam and itch) which exemplifies the form.

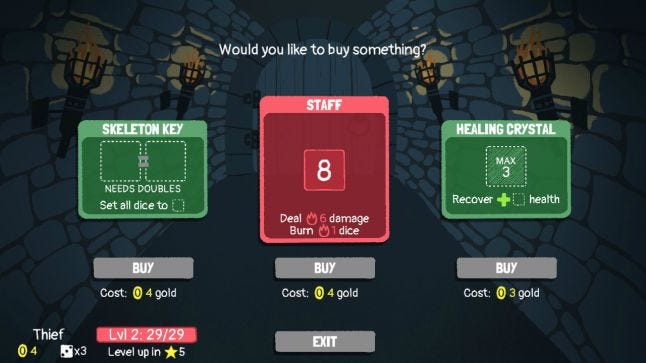

During each round of combat in Dicey Dungeons, the player rolls a number of six-sided dice, and then places the dice into different gear they’ve equipped. So for example, the Sword item takes a dice value of up to five and does that number in damage to the enemy. The Shield takes a dice value of up to four and will absorb damage equaling it, and Combat Roll re-rolls a die played into it. The turn ends when either each piece of gear has been used up, or all the usable dice have been played.

It’s a simple concept, and it amounts to playing the odds of getting certain values and using good strategy to manipulate them to your advantage. And while Dicey Dungeons is still a few months from final release, Cavanagh already thinks it’s one of the best games he’s yet made.

“Sometimes it just clicks and you know you have something,” he says. Being as incredibly modest as he is, that’s a strong statement.

"With RPG combat, that stuff really gets fun when it becomes the right mix of randomness and deliberate plans coming together."

One of Dicey Dungeon’s highlights is way its classes riff on its core rules. The Warrior is straightforward, about dealing damage and managing defense. The Thief, by contrast, is more about doing multiple hits via splitting dice into lots of lower-value dice. The Inventor destroys gear to make new gear, and the Witch, well, you haven’t played a class quite like the Witch before.

Cavanagh’s design process behind the Witch is a great illustration of why Dicey Dungeons is such an interesting progression for the genre. But it arose from a core design issue he identified with his game.

He calls it the equipment problem. In any battle, he says, you’re forced to use whatever you have equipped. This means your options and ability to deal with each challenge are limited because you face each new enemy with equipment that you unwittingly chose in the past.

“I realized very quickly that all the characters are going to struggle with that, so every character in my head I think of them as having a different way of dealing with this equipment problem.”

The Warrior gets equipment that either takes dice of any value but isn’t very powerful, or it requires low-odds dice but rewards successful rolls with powerful status effects. The Thief automatically gets to use a random piece of the enemy’s equipment each turn, a wildcard that often holds the key to defeating it. The Inventor’s equipment is constantly shifting.

“The Witch came about initially from trying to figure out, OK, what if we have a character that doesn’t have any equipment at all? What would that look like?”

So started a long series of dead ends and mild panicking, as Cavanagh found himself spending way longer finding the solution to this idea than he planned.

His initial idea was that rather than equipment, the Witch would have a complicated skill card which the player would have to learn to use and manipulate, and his first expression of it was inspired by magic squares, the math puzzle game in which you have to fill up a 3x3 grid with numbers that mean the rows and columns add up to certain totals.

“So what if you could fill in spaces in a 3x3 grid with dice and with certain totals, or you fill in a full row or column, you got to deal an effect?” The top row, for example could be a fire spell, the middle column a healing spell. And if you placed the dice just right, you could trigger more than one.

“That was what I tried to implement. It didn’t work, obviously.” Cavanagh laughs. On paper it sounds like a great idea, but in practice, he found huge problems.

First, he discovered that half the dice the players rolled were unplayable, because the grid wouldn’t take them. “Having dice left over is the worst feeling in the game,” he says. “With any class, if you get to the end of your turn and you have a bunch of dice sitting there you feel like something [has] gone wrong.”

He also couldn’t quite see how the class would level up. Perhaps with larger grids that granted access to more abilities? But since the dice were getting wasted, Cavanagh realized that he needed to give the player more control over what the rows and columns added up to, and yet spells had to have static values in order to be triggered. And that meant that they wouldn’t be able to do the variable effects that other classes’ gear would deal.

In a second implementation he tried a design where the player would apply different actions they found to the columns and rows, a way for them to develop a build. “But that didn’t quite work because the core idea of the magic squares, rolling certain numbers and filling blanks, wasn’t working. I thought about having random numbers every turn so you could have a little bit of unpredictability, but it wasn’t fun.”

At this point in Dicey Dungeons’ development, Cavanagh was releasing a new build every other week or so, and he was well into his second week of developing the Witch. Worried he was getting nowhere, he ditched the magic squares concept in favor of a spell book.

It would work a little like a deck of cards: you’d pick spells up from the dungeon and only be able to see the top five, and each would trigger on certain dice conditions: even values, a double, a six. Whenever you played dice, they’d cast any of the spells that matched. So you might have a fire spell that required even rolls and a spear spell that required a six, and both would trigger on playing a six.

“I was really sure about it this time, but it wasn’t fun either!”

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

The problem was that spells would fire off at once, and you couldn’t tell what was happening and why. “It felt a random avalanche of status effects and damage and new dice appearing, just totally random. So at that point I was kind of a bit worried, I think because I’d tried all these ideas and the character wasn’t coming together.”

But in this idea lay the kernel of the Witch’s salvation. One of the spells Cavanagh tried out summoned equipment that would lie alongside the spell book to give extra options. “I think this was the critical discovery for the character and it immediately fixed so many problems. I could tell right away.”

Summoning equipment felt more deliberate, giving a sense of building up a set of options that players could plan around, rather than relying on base luck. “It was no longer a random avalanche of events, it was a sequence you were planning,” says Cavanagh. “It worked so well that I thought, what if every spell summoned equipment? And that’s how I got to where the game is now.”

And yet by re-introducing equipment it rather flew in the face of what he’d intended the Witch to avoid, and wasn’t summoning just an extra level of faff for players to go through? “I thought it would be disaster,” he admits, but he’d overlooked the importance of allowing the player to make plans. “It stopped feeling random because it was this deliberate thing of deciding what equipment you wanted to come out.”

From here, the Witch evolved through a lot of simplification. Rather than a deck of spells, the spellbook became six slots, one for each face of a die. As you go around the dungeon you get more spells which you can choose to include in the book. Roll a slot during a battle and the spell becomes one of your four actions; you can have more than one of the same spell and swap them in and out during the battle. And you can throw your leftover dice at the enemy for one damage if they’re otherwise useless. Every action feels positive.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

“There are still problems,” says Cavanagh. The Witch is still prone to get stuck, failing to roll the number she needs for a critical spell. So he added Cauldron, a spell that rerolls the die played into it, doing one damage to save it feeling wasteful.

"The core thing in Dicey Dungeons is...you have a static planned set of equipment and every time you face an enemy they always do the same things, but then there’s this random element [dice rolls] that feels very fair...There’s something that’s really fundamentally correct about that approach to RPG combat, I think."

“Any kind of dice manipulation that’s predictable was pretty fun, like Lockpick.” This ability splits a die into two random dice, so put a five in and you might get a two and a three or a one and a four. “That ended up to being a really powerful card for the Witch so you always find it in the first shop now.”

Another problem was that the first public appearance of the Witch, in early June’s version 0.8, started out with six useful spells already loaded into her book, and Cavanagh noticed that players tended not to replace them with those they found in the dungeon. So the second public iteration gave the Witch just two starting spells and boosted the power of subsequent pick-up spells.

That’s where the Witch stands now. Before Dicey Dungeons’ final release in late fall or so, Cavanagh intends to overhaul all the classes and he wants to give her better counters to enemy elemental magic, and the first few rounds of each battle to be more dynamic and respond to the enemy type, because at the moment the best start is to simply invest in Hall of Mirrors, a spell which gives you more dice each round.

At it's core, though, the Witch is already very rewarding -- striking the heart of Dicey Dungeons’ formula.

“With RPG combat, that stuff really gets fun when it becomes the right mix of randomness and deliberate plans coming together,” Cavanagh concludes.

“The core thing in Dicey Dungeons is that you have a static planned set of equipment and every time you face an enemy they always do the same things, but then there’s this random element that feels very fair, which is that all your actions are dictated by dice rolls. There’s something that’s really fundamentally correct about that approach to RPG combat, I think.”

You May Also Like