Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

“This is sort of a solution to the discoverability problem, right?" Zach Barth said of his new puzzle game Shenzhen I/O. "To make something that is really unique and that you have an audience for."

Last month, Zachtronics launched the Early Access version of Shenzhen I/O, a game about running away to China to join an electronics company, design circuits, and write code.

It's a spiritual successor to TIS-100, the coder puzzle game that Zachtronics quietly launched last year. That title was the definition of niche -- it describes itself as "the assembly language programming game you never asked for" -- and it was virtually invisible to everyone outside of the specific audience it was aimed at: programmers.

"Niches are big nowadays,” developer Zachary Barth told me last year. “There's a lot of programmers, it's easy to reach them because they're all playing computer games for the most part, and they all have money! So it's not a bad niche.”

When I interviewed Barth and fellow developer Matthew Burns last month, they confirmed that TIS-100 went on to outsell Zachtronics' far more approachable 2015 puzzle game Infinifactory by a factor of roughly 2 to 1. However, since TIS-100 is currently $7 on Steam compared to Infinifactory's $25, Barth says it was "kind of too cheap to be super-successful."

Shenzhen I/O is Zachtronics' attempt to build on the success of TIS. The game is aimed squarely at the same niche coder audience, but it has a more approachable interface, a cast of characters, and a higher price tag (Shenzhen is currently $15).

Shenzen I/O invites players to "Read the manual, which includes over 30 pages of original datasheets, reference guides, and technical diagrams"

The two devs seem excited about the prospect of building up a core audience of people who yearn for games about solving puzzles through programming. Barth compared it to the "Spiderweb Software model," referencing developer Jeff Vogel's knack for surviving and thriving by making games for a niche audience (in Vogel's case, isometric RPGs).

"I guess this is sort of a solution to the discoverability problem, right? To make something that is really unique and that you have an audience for."

“I guess this is sort of a solution to the discoverability problem, right? To make something that is really unique and that you have an audience for,” said Barth. “I can put out the word and it only takes a couple weeks for a lot of people to return and come back and be engaged and excited about it.”

By many accounts we’re living in the wake of an indiepocalypse, so any insight into how small studios survive and thrive in 2016 is worth chasing. But there’s more to learn from the story of Shenzhen I/O's development, I think -- lessons about how people tell stories about themselves through the things they create.

“How we tell the story is the puzzles themselves,” said Burns. “The puzzles themselves are the products. And then the products themselves illuminate the world that you live in.”

More on that in a moment. First, let's talk about sales: Barth says Shenzhen has been seeling faster than its predecessor (and just about any Zachtronics game, apparently), reinforcing the notion that it's possible for game developers to carve out careers making the sorts of games they love for the people who love them too -- even if those games happen to be about working at fictional Chinese electronics firms designing fake security cameras and light-up vape pens.

The game tasks you with coding and engineering products for clients. Sometimes, those are games and game accessories. Other times, they're fake traffic cameras or sandwich makers.

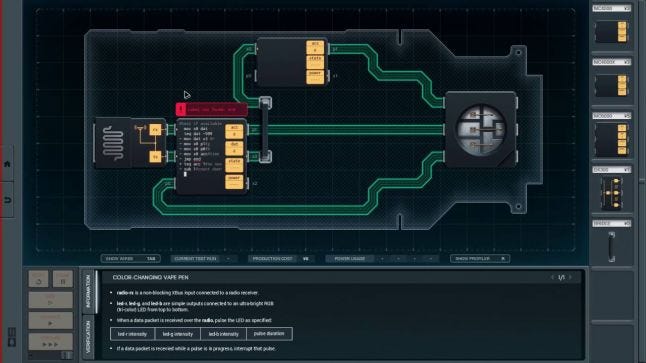

At one point Shenzhen I/O challenges players to create radio-controlled LED vape pens for a musician Barth calls “Cool Dad”, and it turns out if you want to know where Shenzhen came from, Cool Dad is key.

Cool Dad links Shenzhen I/O to The Second Golden Age, the ideal open-world programming game Barth dreamed up years ago and then took a shot at creating during a lull in Infinifactory’s development.

That effort didn't pan out, but it did lead to the development of TIS-100, which Barth described last year as a sort of standalone version of what he’d originally envisioned to be a discrete set of puzzles in Golden Age. A key element of this massive puzzle game he’d envisioned was that players were expats in a strange land, often solving puzzles to build things at others’ behest. Those things were artifacts that would then tell the player something about the world they were exploring, and the characters they were serving.

“In Second Golden Age most of the things that you were doing, they were artifacts. Maybe you'd do some chemical synthesis, but you're designing a designer drug for a person to use,” Barth said. “Even Cool Dad; we created this character called Cool Dad who's like a musician, but like a dubstep Kid Rock. He's really popular; nobody really likes him, but he's really popular.”

Now, in Shenzhen I/O, the player steps into the shoes of an engineer who moves to a near-future China in order to make things. It is, as Barth puts it, “straight up the story from The Second Golden Age,” and Cool Dad also makes his presence known in Shenzhen by putting in an order for a truckload of light-up vape pens.

“You know when you go to a concert and they give you the glowsticks that light up with the music?” Barth said. “Cool Dad did that except they're all vape pens, so it's just like an audience full with a thick haze of vape smoke and everybody is vaping, but then the vape pens are flashing to the music. It's very -- People pay a lot of money for that shit in 2026.”

Since Shenzhen I/O players learn about the game's world through email conversations with coworkers, they never meet Cool Dad. They never communicate directly with him; the only way they learn about him (if they care too at all) is by putting together the thing he wants, and thinking about why he wants it.

This is, incidentally, the same approach Zachtronics took in designing the puzzle.

“You just kind of work backwards, right?” Barth said. “We came up with the idea for the vape pen first. Right, we're like, ‘What would Cool Dad give away at a concert that proves how awful he is?’”

There’s something worth highlighting here, this notion that game designers can turn even seemingly banal items like disposable concert tchotchkes into intriguing puzzles. According to Barth, Zachtronics often designs such puzzles by working backwards -- figuring out what makes sense for the world, then stepping backwards through the puzzle-solving process.

“So we had this idea, and we say, ‘Okay, so it's like a vape pen. What can you do?’” Barth said. "I think specifically for this one it was like, ‘How can you make a vape pen more interesting than just a vape pen?’ You (Burns) had just been to that concert….”

“Yeah, I went to the Hatsune Miku concert,” Burns chimed in.

“They gave you light-up things that go with the music or whatever. So I thought, ‘Oh, that's electronics,’” Barth continued. “ So if this were a real thing in this real universe of being at the Cool Dad concert, they'd need to be able to turn the LED to a certain color and flash it and do all this stuff. So from there [our puzzle design process is] pretty straightforward: Let's design this product for real. What would you do if you were actually designing this product? You'd have a radio that turns it on and off -- Then we just built the puzzle to be that.”

That also means that when a Shenzhen I/O player solves a puzzle, they’ve also designed something that approximates the functionality of a real product in the real world. They get an intimate understanding of what that thing is, how it fits into the fictional world of the game, and what the characters in that game think about it. That inin turn sheds light on who those characters are and how they feel about spending their lives building things for others, like a light-up vape pen to be mass-produced and used for effect at a Cool Dad concert.

"To sort of be involved in this peripheral way with something larger like that, to me that echoes experiences I've had working on AAA games," says Burns, who has credits on multiple Halo and Call of Duty games. "Like you've played this really small part in this weird thing that's this cultural phenomenon somewhere else and you did this thing for it. Making a vape pen for some famous concert, that kind of thing. For someone who works on a big AAA game it's like, 'I did the sound effects.'"

"Yeah," chimes in Barth, with a laugh. "Like 'I modeled all the bushes in Mass Effect 3.'"

Both acknowledge that game developers who have worked in large companies may find Shenzhen I/O's in-game email chains and exchanges eerily familiar. The game's characters are all tech company employee archetypes, but Burns says they're pretty much all inspired in some way by previous real-world experiences.

"There's a moment in Shenzhen I/O where the email thread turns into Chinese for a little bit. It's not a big moment or anything, but they just start talking to each other in Chinese without caring if you can read it or not," said Burns. "That's kind of directly inspired by Zach's experience working with HTC at Valve."

Burns says he initially came up with a few different character concepts while designing the narrative for Shenzhen, and as he was writing out their messages Barth began to recognize in them aspects of real people he'd worked with in various jobs.

"Oh, I recognize these characters," said Barth. "I worked with this guy at Valve."

"Or Microsoft, or wherever else," added Burns.

"God, yeah," responded Barth. "They're all real people, whether we knew them or not."

Barth worked with Valve for roughly ten months, and he says that while he never went to China during that time (in fact, he's never been to China period) he would occasionally meet with HTC representatives over from Taiwan. Some of the email exchanges in Shenzhen I/O are very similar to the exchanges he'd have while working at Valve, and both devs acknowledge that a core piece of Shenzhen's appeal is the way it presents a sort of ideal version of work.

"It takes out the stuff that's unfun about real work," said Burns. "In your real job there's so much more corporate politics and bullshit and probably stuff that you don't want to do. Like [Shenzhen I/O] is like work, like it evokes that, but it's also the funnest version of work possible."

Take a break from coding to playtest a game-within-the-game version of solitaire.

Take a break from coding to playtest a game-within-the-game version of solitaire.

This, then, is perhaps the most interesting thing about Zachtronics' games: they seek to offer a fantasy of perfect employment. In Shenzhen I/O, that means you work for a big tech company but you don't have to write a bunch of email. You don't have to go to a ton of meetings with people you don't like, or don't want to listen to. You don't have to worry about whether your product will sell, or whether your company will founder -- because it's a game. What players do in games like this and TIS-100 can look like drudgery, but Burns and Barth believe the games are successful because they distill the day-to-day work of engineering down to what makes it satisfying: solving puzzles.

"I think people tend to actually like work and find it to be very purposeful until we ruin it. We ruin it by adding politics and we ruin it by just making it demoralizing," said Barth. "These games are very much about work, but...it's the fun part of work! This is what everybody wishes all life could be, right? This is what I wish all life could be like."

"And like I said, you never have to go to a company all-hands meeting for two hours..." began Burns.

"Unless you want to!" Barth interjected.

"Well..." Burns continued.

"In the game you certainly can't," added Barth, laughing.

"We didn't...we didn't build that in," said Burns. "Maybe next time."

Despite it's near-future setting, the pair also see Shenzhen as a way to offer perspective on what life can be like in modern-day China. This is something they suggest more Western devs should be doing: looking at China as more than either a far-away land riddled with either mystical mumbo-jumbo or nebulous threats.

"I actually can't think of another Western developed-game that is set in China that isn't like, kung fu and dragons and stuff, or about like the Triads and mob stuff. What about normal, everyday life in China?" Burns asked. "What about Chinese characters who are kind of like everyday characters, characters who are just living their lives? I can't think of another game that really just has normal everyday life. China's always this very exotic thing, one way or another."

In Shenzhen, China is the place you go when you want to make things, because that doesn't happen in America anymore. Barth says it turned out to be a way for him to examine the anxiety-inducing way China is often portrayed in Western media, and to try and paint a picture of China as a place people don't need to be afraid of: a place where good, normal people work and play and deal with ridiculously long email chains while they try to build a better vape pen.

All of this, of course, is still wrapped up in an engineering puzzle game with a 30+ page manual that's meant to be printed out, ensconced in a binder and referred to during play (one of the game's selling points is to "read the fucking manual.)

Barth and Burns are proud of that manual, and Barth admits Zachtronics has a real wheelhouse going when it comes to making puzzle games about abstract engineering challenges, but he's quick to push back on the notion that the studio's niche is just those kinds of games. It's more about a process, he says, a way of approaching game design and creating "novel gameplay experiences" by looking at the world through the eyes of an engineer. That, he hopes, is the edge that will help Zachtronics carve out its own niche in the game industry.

“I think that's sort of literally the best you can hope for is you can that you can keep doing it,” said Barth. “That's definitely what TIS, surprisingly, ended up being and that's what Shenzhen I/O has been so far.”

You May Also Like