Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In March 1997, Sony launched the Net Yaroze project, which put the power of the original PlayStation in the hands of amateur developers, and this feature has interviews with developers who got their start on the system, as well as academics who used it to teach.

April 26, 2012

Author: by John Szczepaniak

[In March 1997, Sony launched the Net Yaroze project, which put the power of the original PlayStation in the hands of amateur developers. For well under $1000, hobbyists could get a special PlayStation unit which hooked to PCs and allowed them to develop their own games. This look back at the system includes interviews with developers who got their start on the system, as well as academics who used it in some of the earliest hands-on game development programs in the world.]

Today, with the ease of online distribution, it's easy to forget what things were like 15 years ago. Now all consoles -- even handhelds -- have download services, and in the case of something like Xbox Live Indie Games, anyone in their pajamas can tinker with the hardware.

In the mid-to-late 1990s, though, console development was tightly controlled, requiring licensing agreements and expensive development kits. While anyone could program for open platforms such as computers, online distribution was still nascent.

Launched in 1997, Sony's Net Yaroze project aimed to allow ordinary consumers to develop games for the biggest selling console of the time: the original PlayStation. There were limitations designed to prevent cannibalization of the more expensive professional kits, but this was a landmark venture.

Later integration with university courses and the opportunity to have projects distributed via the monthly Official UK PlayStation Magazine (OPSM) demo CD made it even more significant.

Net Yaroze was reportedly the idea of PlayStation creator Ken Kutaragi, and while the project may have been Japanese, it came with a distinctly British influence. Paul Holman, current vice president of R&D at Sony Computer Entertainment Europe, was head of the UK Yaroze division.

"Although the idea would have been approved by Ken," says Holman, "I worked directly with my counterparts in Japan to discuss the practical details. The goal we shared was to allow interested consumers to create their own games on PlayStation using something similar to the professional developer environment. I'd grown up in the days of the BBC Micro, so it was for me very much providing this sort of experience to this generation."

The BBC Micro was one of several popular home computers sold in the UK during the 1980s. The open nature of the platforms and ease of development meant it was possible even for school kids to create a game. Have a parent sign a publishing contract, and then an audio cassette carrying the software would be available on store shelves across the country.

Charles Chapman, developer of Total Soccer Yaroze and co-founder of First Touch Games in the UK, also describes how coding in his youth made Net Yaroze the perfect fit: "I had been involved in making games years before on the ZX Spectrum, and Amiga/ST while I was a teenager, so I was always keen on making games. But in the late 1990s there were limited avenues into the industry, so the Yaroze arrived at a great time."

Total Soccer Yaroze

Longtime magazine editor Ryan Butt, who helmed OPSM during its final year and gave the Net Yaroze much support, explains his initial reaction: "I first heard about it when editor on Play magazine, and was intrigued by the prospect of a return to bedroom coding -- although the cost of the machine was high and I was unsure if it offered enough range and freedom for would-be coders to realize their ideas." Once given the reins to OPSM, and able to choose the demo disc content, he was impressed. "We shoehorned as many Net Yaroze games in as we could. Some of them, like TimeSlip, were actually pretty bloody good!"

With Europe, America, and Japan's developers having very different backgrounds, we asked Holman if there had been resistance from within Sony. "I didn't encounter any barriers from other departments, although the project was very much led from my department, which was focused on helping game developers get the best technically out of PlayStation. To become a Net Yaroze member, there was a basic legal agreement under which we provided the SDK, which was a slightly cut down version of the professional one, and under which members could share their work on our server."

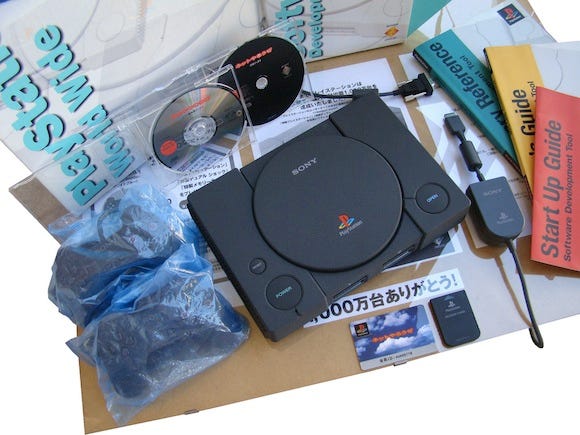

Buying into the Net Yaroze club got you a region-free black PlayStation along with serial cable for connection to a computer, two controllers, various discs, dongles, manuals and coding libraries, plus access to Sony's private forum. Although there were price drops it was still a big investment, initially costing £550 / $750.

Amusingly, SCEE were pretty relaxed about depositing checks, as revealed by David Johnston, who developed TimeSlip and went on to form Smudged Cat Games. "I remember it being a big decision buying a Net Yaroze, because I was at school at the time, and they were pretty expensive. I never paid for it, though! Sony just never took the money. I guess it's been long enough now they can't chase me for it!"

TimeSlip

The community spirit which formed on the private forums was an important part of the experience, as Holman and other SCEE staff provided technical assistance for the aspiring developers, while they encouraged each other with jovial banter and attempts at one-upmanship.

"Someone made a game called Down, where the character dropped down the screen. I saw it and decided to make a game called Up, for a laugh," says Johnston. "A bit of light-hearted rib jabbing. At first he didn't see it that way though, and posted on the forums how outraged he was, and that he was planning to make a game called Up -- oops! We got in touch and he realized no harm was intended."

Down

Everyone contacted for this article had only fond recollections. James Rutherford, who later worked on Stuntman and developed tools for Driv3r, describes the excitement of visiting the forums. "It wasn't perfect, but Sony provided a great base and the community spirit made up for any shortfalls. Paul Holman (and team) provided some top technical support. There was usually something new every day from the SCEE site, and digging through the FTP there were some excellent games."

"I expect most other students were out being social, while I was spending far too much time in the evenings tinkering."

Robert Swan, developer of Adventure Game, who went on to work for SCEE and later founded indie studio Aah Games, has similar recollections. "It directly related to me failing my degree -- I spent so much time having fun mucking about that [my university] course became mundane and I 'accidentally' missed lectures and exams! I have almost nothing but great memories of the Yaroze -- it gave me a focus for games development and started the career I love."

Of course Net Yaroze wasn't the first instance of officially-sanctioned bedroom coding on consoles (for one, starting in 1984, Nintendo developed several versions of Family BASIC for its Famicom). Nor was Sony the first to integrate itself with academia, since in Japan there were already game development schools. But the Net Yaroze still broke new ground when the University of Abertay Dundee in Scotland started its Master of Science course in Computer Games Technology in 1998, helped by developers such as DMA Design (later Rockstar North).

Abertay professor Ian Marshall explains. "It generated worldwide media attention. We made contact with Sony through Scottish games companies such as DMA Design and the course was designed with the help of former students -- such as David Jones of Lemmings and GTA fame. They approached Abertay because we'd provided most of the founding staff for DMA. When they were looking for new staff I said I could deliver the graduates if they could help design the course and support its delivery."

Other universities followed, including Middlesex and Hull Universities. Rob Miles, lecturer in computer science at Hull, describes its start: "We constantly updated our course content and had an opportunity to get hold of some Net Yaroze systems. They were used in our postgraduate graphics course, and also as the basis of final year projects for undergraduate students. Then after a while new things came along and we threw them out -- but I still kept one in my office."

As Swan reveals, however, not all universities delivered on their promises. "Middlesex University was loaned units by SCEE for their games programming course, which unfortunately never materialized. Despite the cancellation I still tracked down the lecturer while on my replacement course. I borrowed a Yaroze for home and later got my own when the addiction kicked in."

Sony proved a keen supporter of British universities, as further detailed by Professor Marshall from Abertay: "I think having many UK games developers as supporters, and the media attention, encouraged Sony to help us. SCEE donated something like 40 Yaroze and gave us substantial discounts on other equipment. We were also given excellent support by Holman."

Professor Marshall also elaborates on the situation in Japan: "We knew about a number of Yaroze courses offered by universities in Japan. At the time we had a very good relationship with Gifu University, and routinely had staff based there for several months doing VR research."

Although the Japanese side of Net Yaroze produced some technical marvels, cross-communication between regions was limited. "Everyone had access to all the territories' newsgroups, although they were separately listed," says Swan. "The Japanese groups were quiet -- we couldn't talk to them because of the language. Occasionally there was a new game, like Terra Incognita, and they'd blow us away!"

This sentiment is echoed by former triple-A developer Matt James of Hermit Games. "The language barrier kept the Japanese scene separate, but they did the most -- running competitions and incubating the best Yaroze teams as Sony teams."

Some of the most impressive Net Yaroze games came from Japan, including the Resident Evil-inspired Yakata (aka Super Mansion), Wipeout-style Hover Racing, and perhaps the most popular, the action-RPG Terra Incognita. Terra Incognita recalls cult classic isometric Sega Genesis action RPG Landstalker, and came close to the level of a commercial release. It was later ported to iOS.

Hover Racing

Now working for Square Enix in Japan, Terra Incognita lead programmer Mitsuru Kamiyama explains that game development started as a hobby for him "I found out about Net Yaroze while I was a student and saw an advertisement in a game magazine. I remember I had no savings at that time and yet paid 120,000 yen (around $1,500) which then resulted in getting my electricity pulled. At that time in Japan, the internet was not very common, but its community was active and we were able to gather various works for contests."

Terra Incognita

In contrast, the U.S. side of things appeared less active, at least from the perspective of those interviewed. According to Matt James, "There were a few U.S. people who came on the European newsgroups, but there didn't seem to be any scene over there. SCEA seemed to do the least to encourage it."

Swan concurs. "The U.S. lists were a bit quieter than the European ones, although there was occasional cross-chat. I think we were lucky in that our members were very interested in community talk and action, and the SCEE support seemed more tangible."

When asked why SCEA seemed very cold to the Net Yaroze, especially given the lack of coverage in U.S. magazines, Holman was keen to state this was not the case. "I don't think SCEA was 'very cold'. Indeed, they had comparable numbers of Net Yaroze members to SCEE. Certainly, all the regions worked with universities, and perhaps we were simply luckier in Europe to have a more fertile ground in terms of interest from universities and magazines. Which again might be due to the culture of the BBC Micro."

The international success of Net Yaroze raises an interesting point, since Sarah Bennett, product manager for Net Yaroze in the UK, was quoted as saying there were "several thousand" users worldwide. This would imply there were thousands of projects in development -- far more than were revealed to the public on the OPSM demo discs.

Holman expands on this. "Sarah was right; we certainly sold around 1,000 Net Yarozes [in Europe], with more being sold in Japan. U.S. was similar to our numbers. Although they were as cheap as we could make them, they were relatively expensive, and so people bought them specifically to work on projects -- so probably thousands of projects!"

Dr Henry Fortuna, one of those involved with the Net Yaroze course at Abertay, reveals how little the public actually saw. "There were some impressive demos produced but these were mainly internal to Abertay." Professor Marshal added: "We didn't start making them more widely available until we launched the Dare to be Digital competition for student teams to develop prototype games."

"I don't think we'll ever know exactly how many Net Yaroze games there were," says Smudged Cat's Johnston. "There were so many made that never saw the light of day because they could only be played by the Yaroze community -- decent games that never made it to OPSM cover discs."

Sony produced various promotional discs with Net Yaroze games, but in Europe the monthly demo on OPSM was the only regular way for non-members to access the games. Between issues 26 and 108 of OPSM there were at least 37 different games given out. While there were lengthy periods without Net Yaroze games on the demos, this was down to the whim of changing editors.

Ryan Butt explains that, as editor, he had access to everything. "We had full control of what went on the disc. We had a database of Net Yaroze titles and provided Sony with a list of what we wanted. Later in OPSM's life, the new demos dried up so we chose from the existing. Yaroze games were small and acted as good space fillers, bumping up the 'number flash' of featured games. It made sense to pack as much on as possible."

Even with the database, though, what was available to OPSM's editors was limited by the suitability of certain games. Johnston has an amusing anecdote: "There was certainly a bit of discussion, and some changes had to be made before the game was actually deemed ready for a cover disc. They didn't just go ahead without asking. I remember putting a picture of my face on the title screen of TimeSlip because I thought I'd try to grab a bit of fame. I was politely told that wasn't really suitable!"

The difficulty of getting a completed game noticed outside the boundaries of the community was mentioned by all those interviewed. When asked about the Net Yaroze's main shortcoming, Matt James sums it up neatly: "Distribution. Once you made a game there wasn't a way to get it to players without a Yaroze. In the UK there was a chance you could get the game on the OPSM disc, but it wasn't guaranteed."

Robert Swan agrees. "Progress was far slower than with things like XBLIG today. Not being able to release our games for others to play was a frequent frustration." He also highlights problems regarding some people's expectations: "It was common that people bought one and posted on the newsgroups disappointed they needed to program. While SCEE helped where they could, we generally weren't very good programmers and didn't even ask for help constructively!"

James Rutherford, meanwhile, mentions other limitations. "I was disheartened to find that some stuff I wanted to do just wasn't possible with the Yaroze libraries, particularly multitap support -- I wanted to write four-player games!"

The technical limitations of the Net Yaroze kit are well documented. Data couldn't be continuously streamed from the host computer or CD, meaning the entire game had to fit into roughly 3.5mb. "The connection with the PC was the biggest slowdown," says Charles Chapman. "It was over a serial cable, so was very slow. The other limitation was that your entire game had to fit into main memory. This wasn't so bad, as the type of games people were making were pretty small, but it did mean that the scope was limited."

Professor Marshall talks of other limitations, detailing in one example how it encouraged students to question whether simulated realism was actually preferable to faking something, which required less system resources and would be good enough for games.

"The Yaroze was a compromise," he says, "but it was close enough to the experience of console development. It didn't have the luxury of vast memory like in a PC environment. If students wanted to do something spectacular they had to work [within] the constraints of processor speed and it forced them to optimize code. Yaroze was also great for learning about host and target programming. In terms of preparing them for jobs, it was the only way to get console experience."

In spite of the steep learning curve, technical limitations, and difficulty of getting a good game out there, the tangible benefits of being an active Net Yaroze member outweighed everything else. For those who got involved, having a completed project proved invaluable on a resume. Landing a spot on the OPSM demo was even better, since it could be taken to interviews as part of a portfolio.

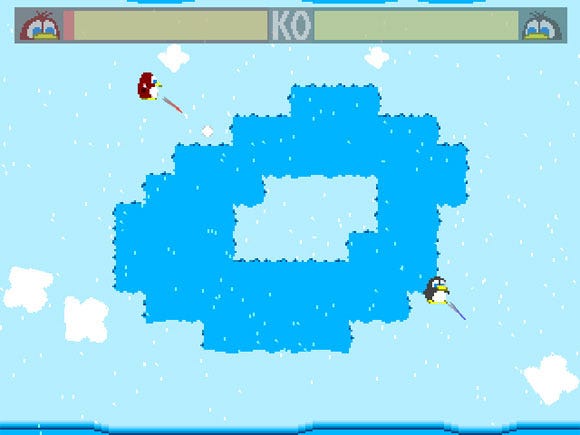

In cases where a project wasn't on the demo, Rutherford devised a workaround. "I'm sure my job placement was [due to] my experience with Yaroze. I went to my friend Nick Ferguson's flat to make a VHS demo tape of my stuff -- him simultaneously pressing record on the video recorder and CD player, with me playing the game. I also had the first version of Snowball Fight on a CD that could be played in a consumer PlayStation. SCEE burnt some as promo items, which helped a lot."

Snowball Fight

Nick Ferguson was also a prolific contributor to the Net Yaroze scene, getting involved after seeing Rutherford's work. "Hardcore programming was never going to be my strength, but the experience of working with Yaroze definitely helped me get my first job," explains Ferguson, who later went on to work for Electronic Arts and is now at Microsoft Studios.

According to Matt James, Net Yaroze also helped build contacts. "I basically walked into PlayStation contracting by knowing enough from a year or so Yaroze work. The private community had a few professional games coders active on the newsgroups. It was an entry into a closed professional world -- who to contact and how."

"At the time there were nearly zero courses teaching games development and information on homebrew for consoles was minimal, so we were pretty appealing to games companies," says Swan.

Like everyone else, he also says it landed him employment. "On the newsgroups the most vocal and productive consisted of roughly 10, all of which are now in games. I got my first job at SCEE directly through the staff I met via Net Yaroze. My first job was working on the PocketStation, which I was saved from by its non-release! I stayed there until The Getaway debacle four years later, which turned me off the 'large team and the sky's the limit' mentality."

In Japan Net Yaroze experience also helped with jobs -- the three-man team on Terra Incognita all landed placements at T&E Soft, while Kamiyama later moved on to Square Enix. He feels you can see the connections. "I've always thought that I'd like to create a game like Terra Incognita for work, and not just as a hobby. As the Square Enix director and programmer who led projects like Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles: Ring of Fates and Echoes of Time, I can say that the game systems are very similar to that of Terra Incognita."

Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles: Echoes of Time

There was even a Yaroze game which went commercial -- sort of. "Total Soccer wasn't really a Yaroze game which became commercial, but it was a game and engine which led to commercial success as a result of the Yaroze," explains Chapman.

"Originally developed as a PC game, it was the Yaroze version which had the most impact. It was shown at [trade show] ECTS in 1998, and through that I met Dave Hawkins, who encouraged me to look into creating a Game Boy Color version. This was released by Ubisoft in 1999 and really changed my career."

Chapman and Hawkins later founded Exient, where things really took off: "The code which built Total Soccer Yaroze evolved into the basis of multiple FIFA games on the GBA and NDS for EA, and also our self-published games, including Dream League Soccer, released in December 2011. What started life as a fairly crude 2D sprite driven game is now a full 3D game with motion captured animation, and a whole host of other tech."

Today he's head of First Touch Games, and continues to develop his soccer engine.

In 2009, Sony's Net Yaroze servers closed, roughly 12 years after the project started. Given how profoundly it affected the lives of everyone involved, each was keen to share their memories and where they see the future of both education and home-made games.

Mitsuru Kamiyama remembers the hard work he and a friend put into Terra Incognita: "When I look back at the game now, it's a bit embarrassing, as it's quite different from modern games. However, looking back, my fondest memory was working so hard with a friend, who helped with the illustration and polygon creation, that we had to carve out time to sleep -- but nevertheless, it was an enjoyable experience."

James Rutherford remembers feeling like a king. "Competitions! SCEE ran a game dev competition and brought about 10 of us down to their London office as a prize. Absolutely brilliant of them, and I felt royally treated. They also hooked up with Scottish Games Alliance for another competition with an awards bash in Stirling Castle."

Robert Swan also recalls the fame and fortune which were (almost) his. "Programming my entry Adventure Game in three weeks for the GDUK competition, getting to the finals in a cool ceremony in Scotland, and then losing to the vastly more polished Blitter Boy by Chris Chadwick. He won £6,000. I was only a bit bitter!"

Blitter Boy

Like many we spoke to, Nick Ferguson agrees that XNA is a successor: "Most people who stuck with it later went on to have success in the industry. I look back on the Yaroze era with a lot of fondness and probably nostalgia. I like to think that if I was 21 these days, I would be doing the same thing with XNA."

Rob Miles even describes how today students at Hull University are submitting XBLIG titles as part of their coursework, adding: "Net Yaroze was definitely a first step to bringing back the 'bedroom coder'. It was an interesting halfway house for those who wanted to make games for a mainstream device without spending loads of cash. XNA and XBLIG are definitely successors to Yaroze, as are the app stores for mobile devices."

Dr. Henry Fortuna of Abertay thinks back to the students he taught. "Yaroze was an inspiring platform. Many students spent long hours in the laboratory developing code. There were a few occasions, particularly close to coursework deadlines, where the cleaners came to the laboratory at around 6 a.m. to find students sleeping on the floor after a busy night coding!" T

Ian Marshall, also of Abertay, also looks back fondly. "The era was exciting; we were breaking new ground in a teaching and research discipline that now everyone has taken up. The industry support was great -- we could not have done it without them."

Today the Net Yaroze servers are gone and the communities disbanded, the University equipment sold off or binned, while the games exist only on scattered demos or in people's memories. Several compilation demos appeared on OPSM, featuring a selection of the best games (notably Euro Demo 42, 77 and 108), though these can fetch high prices on auction. With other projects replacing Net Yaroze, its enduring legacy is now its games. Of the thousands of projects started on Net Yaroze, over 100 have found their way into the wild. Some have even been ported to Windows, XBLIG, and iOS.

In the effort of preservation someone has taken the files and hacked them into a single, mostly functional disc ISO, available online if you look. This is a good place to start for those curious, though as with XBLIG there are plenty of duds and even incomplete projects.

Anything mentioned on these pages is worth looking into; in addition titles such as Haunted Maze, which makes sublime use of the PlayStation analogue joystick; Samsaric Asymptote, with its distinct retro neon graphics; Hover Car Racing, which is different to Hover Racing and more like Micro Machines; or Decaying Orbit, which is an inventive evolution on the idea of planetary landings.

---

Net Yaroze photo taken from Robert Sebo's Flickr. Used and under the Creative Commons license.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like