Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A discussion of the legal issues that come up when portraying a real person in your game.

Whether for humor, social commentary, or just the heck of it, many indie developers like the idea of using a real person's likeness in their game. What they may not realize is that by doing so, they are treading into the contentious legal area called the right of publicity. It is a relatively recent development in the law and evolving quickly, but something every developer should understand before they start modeling real faces for their game.

Imprisoned former Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega unsuccessfully sued Activision over his portrayal in Call of Duty.

Imprisoned former Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega unsuccessfully sued Activision over his portrayal in Call of Duty.

What is the right of publicity?

The right of publicity is a legal right that lets a person control how his or her likeness is portrayed in the media and to profit from that use. Legal nerds like myself categorize it as a hybrid of privacy and intellectual property.

Anyone attempting to sue under the right of publicity must show four elements: (1) use of the plaintiff's identity, (2) appropriation of plaintiff's name or likeness to the defendant's advantage, commercial or otherwise, (3) lack of consent, and (4) specific injury that resulted. In addition, California has a law codified as Civil Code Section 3344 allowing for minimum damages of $750 per violation. Whichever state you operate in, the right of publicity is serious business. How then can you portray a real person in your game while minimizing your risk of a lawsuit?

Licensing

The first and easiest way to handle the right of publicity is with a license. That is to say, you pay for it. Like other forms of intellectual property, the right of publicity can be controlled by a contract, called a license. In a right of publicity license one party grants the rights to use his or her likeness in exchange for something of value (usually money). Most appearances by people, famous or otherwise, are handled this way with little incident.

However, not all licenses are perfect. Sometimes they leave gaps that lead to lawsuits, or sometimes negotiations break down and the licensor (person selling their likeness) decides not to sign the contract. Or perhaps a license is just too expensive for a small independent studio. If you were to go ahead an use the likeness anyway, you run the risk of a lawsuit. However, a lawsuit is not necessarily the end of the world. In such cases, courts have developed a couple of rules for when using a person's likeness violates their right of publicity and when it does not.

Transformative test

One prominent test for the right of publicity is the "transformative" test articulated in Comedy III v. Gary Sanderup. In that case, the California Supreme Court said that if the use of a likeness is "transformative," then it does not violate the subject's right of publicity. A use is transformative if the subject's likeness is merely the "raw material" of the work, which the artist then uses to create something new. However, if the likeness is the "sum and substance," then it is not transformative and the artist loses.

Another important factor is whether the work's economic value derives primarily from the subject's fame; if not then the work is probably transformative, and the artist wins.

Rogers test

The other method that courts use is called the Rogers test after a case called Rogers v. Grimaldi. The test has somewhat fallen out of favor, in part because it is actually a trademark case, but is still relevant especially in the Second Circuit (which includes New York).

The Rogers test asks two questions: whether use of the likeness is artistically relevant and whether the use explicitly misleads the public to think the subject endorses or is the source of the work. If the answer to both questions is "no," then the use does not violate the right of publicity.

The First Amendment and "Anti-SLAPP" Motions

Because these issues involve art and expression, there are some tricky First Amendment issues that come up. When someone sues you over something you express in a video game, they are trying to use the government (in the form of the courts) to suppress speech. That is where anti-SLAPP (SLAPP: strategic lawsuit against public participation) statutes come in. These laws offer protection for First Amendment protected activities by creating a higher burden for plaintiffs to clear in their lawsuits. If the defendant can demonstrate that the lawsuit has no possibility of success in an anti-SLAPP motion, then the court will dismiss the lawsuit and may award damages. In California a successful anti-SLAPP motion will grant attorney's fees as well.

Case Studies

These concepts are easiest to understand by examining specific cases. Fortunately, many of the important right of publicity cases in recent memory involve video games.

Comedy III v. Gary Sanderup

Although it is not a video game case, Comedy III established the "transformative" test for right of publicity. The offending party was selling T-shirt prints with images of the Three Stooges, such as the image above. The California Supreme Court held that the prints were not transformative and relied on the fame of the subjects for their economic value. The defendant had not used Three Stooges' likeness to create anything new.

Kirby v. Sega of Am., Inc.

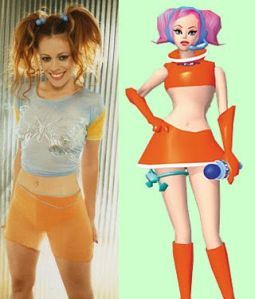

Gamers of my generation will remember the protagonist of Space Channel 5, a young woman named Ulala. They may or may not also remember a real life singer known as Lady Miss Kier who bore a striking resemblance to the Dreamcast heroine. Lady Miss Kier was a 90s pop star known for her catch phrase "ulala" and principally famous for the annoyingly catchy "Groove is in the Heart." She certainly saw the resemblance and sued Sega for using her likeness. However the California Court of Appeal held that Ulala was sufficiently transformative and more than a mere digital recreation of the plaintiff.

No Doubt v. Activision

This case is important because it involved a dispute even though the parties had licensed the right of publicity. In the Rock Band games, Activision had licensed the right of publicity from No Doubt to be in the game, but only to have the digital band members play their own songs. Activision apparently decided that it did not need permission to depict Gwen and friends playing songs by other bads as well and included that in the game.

The court in No Doubt held that simply depicting the band members doing what made them famous was not transformative, and therefore ruled against Activision's anti-SLAPP motion (remember what that is?).

The Football Cases

There have been several high profile cases involving former football players in the NCAA and Madden franchises. It isn't necessary to cover them each in detail, but the interesting thing is how the transformative test and the Rogers test have yielded different results. Generally, courts that applied the transformative test have held in favor of the players, while courts that applied the Rogers test favored the developers. For this reason, the choice of venue and jurisdiction can be extremely important.

Takeaway

While all this law is useful to know, at the end of the day game developers just need to understand where they can draw the line. One takeaway is if you want to avoid a headache, simply avoiding a real person's likeness may be the best course of action. However, if you must create a character based on a real person, do not just copy that person wholesale. The more you change transform the person into a character of your own devising, the better off you will be. So let your creative talents flow and make something new and interesting.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like