Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"Of the many elements that helped establish what we describe as a “folktale adventure,” three contributed most to our design: length, tone, and moral." - Brooke Condolora, co-founder of Brain&Brain

Game Design Deep Dive is an ongoing Gamasutra series with the goal of shedding light on specific design features or mechanics within a video game, in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Check out earlier installments, including the action-based RPG battles in Undertale, using a real human skull for the audio of Inside, and the challenge of creating a VR FPS in Space Pirate Trainer.

I’m Brooke Condolora of husband-and-wife team Brain&Brain, and I acted as artist, writer, and designer on our latest project, Burly Men at Sea.

Before games, I was a freelance graphic designer and web developer. My husband David and I did occasional creative projects together, like short films, until we finally stumbled onto the idea of making a game. We started developing our first, a tiny point-and-click adventure called Doggins, in 2012.

While working on Doggins, we gradually began to realize just how young and still undiscovered this medium is, and that through it storytelling could be pushed in so many new ways. That excitement carried us into a second project, Burly Men at Sea, which we released just over a month ago.

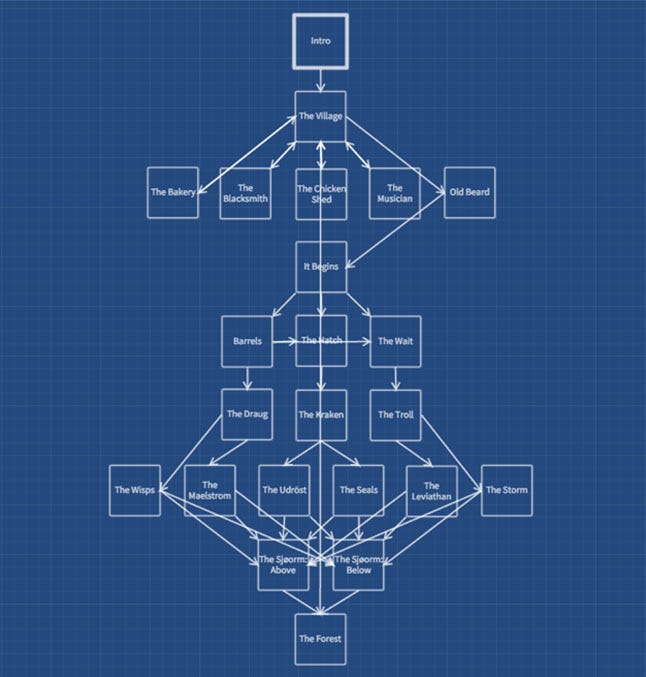

Burly Men at Sea is constructed as a story-building game. In it, branching scenes combine to form a variable tale with a single, overarching theme. With each session, the player returns from one journey to set sail again, uncovering new paths for a series of kindred but distinct adventures.

Of the many elements of folklore that helped to establish what we describe as a “folktale adventure,” three contributed most to the design of Burly Men at Sea: length, tone, and moral. Designing for folktale length gave us a branching narrative with a short play cycle. Designing for folktale tone put the player in the role of storyteller, one step removed from our protagonists. But here we ran into a complication: how could the game present a cohesive moral tale when the tale itself is of the player’s choosing?

Our solution was to structure the story in a way that both beginning and end were consistent, with the player’s influence shaping all events in the middle of the story in a way that developed a single theme.

Burly Men at Sea was always a game about adventure, but it took us about a year and a large-scale adventure of our own to learn what exactly we wanted to say about it—or, ultimately, what it wanted to say to us. One of my earliest notes on the game, dated a full year before we even began development, describes it as “a type of interactive adventure with a moral, drawing from Scandinavian folklore.” While this is a perfectly accurate description of the game in its final state, we continued to explore what form that would take for the next two years.

We began with a far more traditional branching narrative in mind. Dialogue choices would carry the player through a series of trials and back, culminating in a lesson about choices made along the way. But we soon abandoned this direction, drawn more to the idea of using playful interaction to advance the narrative, with a sort of Windosill-like aspect of discovery that would set events into motion. With this in mind, we began to view the player character as another of the folkloric creatures in the game: an unseen being with limited influence. As such, a player could direct the protagonists' attention by interacting with the environment or changing their perspective. The characters might then react to this situational change in a way that moves the story forward.

Once we’d established this framework, we began to work out what sort of story we wanted to tell within it. We had chosen early on to set the story in early 20th-century Scandinavia, so I began to research the folklore of that region and consider what sort of moral tale we wanted to tell.

But I soon learned that each time I held too rigidly to a chosen theme, the resulting narrative felt forced. I tried to write a story to change minds, in which the player was always wrong. I tried to write a story that pretended to be what it wasn’t. And finally, it occurred to me that it’s actually not fun to be “taught a lesson.”

What makes an ending satisfying is that it neatly puts into words something nameless you’d already begun to discover for yourself. So I began to write instead with the loose idea to explore the nature of adventure myself, rather than approach it as the knowledgeable party. Looking back, this does seem the obvious route for a story about the unknown, but letting go of intent is a scary to do.

Having set theme aside for the moment, I soon had the rough concept for a journey involving encounters with various creatures from Scandinavian folklore, all taking place at sea. My attention returned to gameplay. How would this journey unfold for the player? I began to develop the village where our characters would set out on their adventure, working from a Norwegian museum’s historical account of life in a local fishing village. As I worked and reworked the location and its inhabitants, it slowly dawned on me that this was not Burly Men at Sea. I hadn’t even begun to develop the setting that made up half of the game’s title—and worse: I dreaded it. Reflecting, I realized that in every seafaring game I’ve played, the least interesting aspect of sea travel is the sea travel. Discovery is interesting. Islands are interesting. Even battles and races are interesting. But endless water and sky quickly become tedious.

The best way to keep our journey engaging, I felt, would be to focus on the encounters as self-contained nodes, with only brief moments of actual travel between. Each node would involve a new creature encounter and, for visual interest, a change in environment (time of day, weather, surface or underwater, island or cave).

Another early choice we made while designing the narrative: there would no wrong answers to choices made in the game. We felt that any story about adventure would be best supported by a world that encouraged exploration and a willingness to take chances, and to that end, no path in the game should leave the player feeling that they should’ve taken a different route.

While we did look to a few other games for reference, the strongest influences on the design of Burly Men at Sea actually came from more traditional media. One that ultimately became the best reference for a branching story with a single ending was O. Henry’s short story “Roads of Destiny.” This was an old favorite of mine that tells the story of a man who comes to a literal fork in the road and chooses one of three ways: right, left, or to return the way he’d come. The story goes on to follow each of these branches to their conclusion, each of which result in different combinations of the same events with ultimately the same fate. It was this method of weaving the same elements into wildly different variations of a single story that guided the shape of our narrative.

After working my way through nearly forty branching variations, I settled on what became the final structure of our story. We’d begin with an intro location that would also serve as a return point (the fishing village), and the story would branch three times during the course of a single journey before meeting again at the end. Each play through would take place over the course of a day and would be designed to be completed in a single sitting.

It was then that I stumbled onto what became the most pivotal piece of the game’s design: the viewport. Inspired equally by the masking ability of fog and by vignette illustrations found in old books, this viewport could be dragged or stretched by the player to direct the characters’ attention and so affect their movement. I immediately began to brainstorm variations on shape and usage: a house shape for building interiors, a flickering ring of firelight, an arched room. These began to combine with a secondary idea of using vignettes to style our narrative scenes like the pages of a book, further pushing the game’s folktale feel. And from this new direction, a more complete narrative theme began to emerge. Our story and gameplay had begun to feel like a cohesive experience.

But the change wasn’t entirely seamless. We had, after all, just attached an entirely new mechanic nearly a year into development. I now had a structural tangle to work through, worried that the game’s use of interaction had become extraneous. Of even greater concern was the possibility that when the viewport mechanic’s novelty wore off, it would become tedious. Somehow, we had to push it further, continue to surprise the player. I sketched out a rough idea for how the viewport might evolve in later scenes, but this only further scrambled my grasp of the structure.

Then, I came across an interview with Nintendo’s Koichi Hayashida, discussing their use of the concept of kishōtenketsu, or four-act structure. In it, an idea is developed over the first two stages, then suddenly goes an unexpected direction before leading into the conclusion. That was it! I hadn’t broken the game: I’d simply lacked the framework needed to contain it.

Equipped with this new lens, I could see how each stage of the game might make the best use of both mechanics, developing gameplay alongside theme. We would use the third act to alter the player’s perception of the viewport and their relationship to the story. Finally, I was able to begin designing the third stage of encounters that would offer that twist, probably one of the most difficult and enjoyable parts of the process. Balance was the first challenge: did the branches in each stage match up in encounter type, level of interaction, use of mechanic, and length? How would each branch connect to the next stage? And ultimately, was it possible for all branches with their player-determined outcomes to join up again at our return point? Would we achieve that elusive through line?

Final narrative structure for Burly Men at Sea, as prototyped in Twine.

As I tackled these challenges over the following year and saw the narrative gradually take a final form, I took a fresh look at the design and story as a whole to see what themes had emerged. To my surprise and enormous relief, I found that what the game itself had to say about adventure was better than anything I had thought I wanted to say. It was about adventure for adventure’s sake, about following impulse down an unknown path. Incredibly, or maybe not, even our development process had reflected this discovered theme. We tried a lot of strange ideas that managed to bind together into an honest little tale that taught us how to both tell and live a better story.

You May Also Like