Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

“The industry sees source material as a trade secret,” Video Game History Foundation founder Frank Cifaldi said at GDC today. “We think it’s an educational tool."

Today at GDC Digital Eclipse's Frank Cifaldi, founder of the Video Game History Foundation, hopped onstage to talk a bit about the challenges facing game historians -- and how devs can continue helping to preserve game history.

It was something of a follow-up to his GDC 2016 talk, in which he pointed out (among other things) that the game industry is far worse than others when it comes to preserving and understanding its own history.

“Very very few of our notable games from the past are available commercially,” he said today, reminding attendees that when you look at two big works of the late ‘80s, the DuckTales video game and the John Candy film Uncle Buck, only the latter is readily (and legally) available today.

"I think for a lot of games, it's just too late now"

This despite the fact that according to Cifaldi, “no video game emulator challenged in court has ever been ruled illegal."

"But because we demonized it, instead of embracing it...I think two things happened," he continued. "Old games became the domain of the pirates...and we also, I think, by not getting ahead of it and getting these games back into print through emulation, I think for a lot of games, it’s just too late now.”

“I do think we can stop the bleeding a little bit of we embrace the emulator loudly,” he said. “Emulation is king.”

In a quick recap of the highs and lows of game preservation over the past three years, Cifaldi shouted out Sony specifically for using an open-source emulator, PCSX ReARMed, in its PlayStation Classic mini-console.

“For me this was huge,” he said. “This was Sony saying an emulator written by the community was good enough.”

Over the last few years Digital Eclipse has also put out some of its own remasters, The Disney Afternoon Collection and The SNK 40th Anniversary Collection, and Cifaldi says that’s spurred the studio to think more deeply about who buys these remastered old games and why.

He suggests there are three very broad, over-generalized categories of customers for old games: parents who want to show their kids what they grew up with, collectors, and hardcore retronauts.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

“The hardcore play hard,” said Cifaldi. “We can do so many things without the industry interacting with us at all. We can download every game ever; it’s so easy to go download a MAME set and have every arcade game ever made playable in front of you.”

An entire industry has sprung up around these hardcore fans, ensuring that there are now a ton of ways to load stacks and stacks of games onto a cartridge to play on original hardware, or hack old CRTs to play games in the most vibrant way possible.

“Nobody’s died yet, but god please be careful,” Cifaldi cautioned.

“We don’t even need the commercial games,” he added. “We can translate games that nobody did, and damn well should have,” like Mother 3.

Cifaldi also gave a shoutout to Roll-Chan, a ROM hack of the original Mega Man which swaps in Roll as the main character, and noted that while he tried to contact the author to get the game included in the Mega Man Legacy Collection, it didn’t work out; “probably because he didn’t believe me.”

If releasing, re-releasing, remastering, or doing anything commercial with old games is part of your business, Cifaldi argues that you should be thinking about how to do it in the best way possible. You’re part of preserving game history, and you’re making money doing it.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

And hey, if you happen to be working on a game like this and have access to anyone who worked on the original game, talk to them! They can give you valuable insight into where it came from, how it was made, and how to preserve and showcase it for future generations.

"It's what I like to call a playable documentary"

As an example he brought the SNK 40th collection back up, highlighting how it's less of a straight pack of remasters and more of a "playable documentary".

“It’s what I like to call a playable documentary of what I think is a little strange and wonderful developer from the ‘80s,” said Cifaldi. “Instead of remastering the game, we approached things a little bit differently.”

To give fellow devs some insight into how these kinds of decisions happen, Cifaldi broke down why Digital Eclipse took on the SNK project.

“We're kind of known for our extra material on these games,” said Cifaldi. “In SNK’s case, they made like 60 games in the ‘80s, and we’d still be working on this project if we did all 60 games.”

So while there are less than 60 playable in the package, Cifaldi says the team worked extremely hard to track down all sorts of promotional materials, screenshots, and more assets from all of SNK’s games. They also put in some historical notes, sourced in part from folks who worked on the original games.

“This was important because a lot of this history hasn’t been talked about, even by SNK,” said Cifaldi. “A lot of these guys aren’t getting any younger, so we wanted to educate consumers about who they are.”

He called special attention to the game’s special “jump in and play” feature, which lets players watch a well-played run of every game and then pause at any time to jump in and take control.

“It’s all pixel-perfect because this isn’t video; it’s actually button playback of the game,” said Cifaldi. “That’s how we’re able to scrub through it….and you can just start playing, because that’s the save state.”

Cifaldi suggests this is almost like flipping through a book, pitching it as a great way to let players who maybe aren’t very good at an old game check out high-level play and later levels for themselves.

He went through a few other tricks Digital Eclipse pulled to get classic games like Ikari Warriors playable on modern controllers before seguing into a conversation about how much devs can learn from the good work going into projects like MAME.

“Three years ago I said we should maybe start using MAME,” said Cifaldi. “I don’t think any studios have done that, including us. But here's the thing...we’re all using MAME.”

What he means is, devs can and are learning a ton about how to best emulate old games and adapt them to modern hardware by studying the work that's being done on emulators, even as the work itself is actively unacknowldged by most of the public.

“I think we should stop doing this nudge-wink thing in the industry that we’ve been doing forever,” he said. “This is volunteer work that we’ve been exploiting for decades, in secrecy, like we’re ashamed of it. But we shouldn’t be ashamed of the MAME project."

“I think we should be proud,” he added. “I think we should be shouting out MAME in the credits, and I’m calling myself out and everyone else on that.”

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

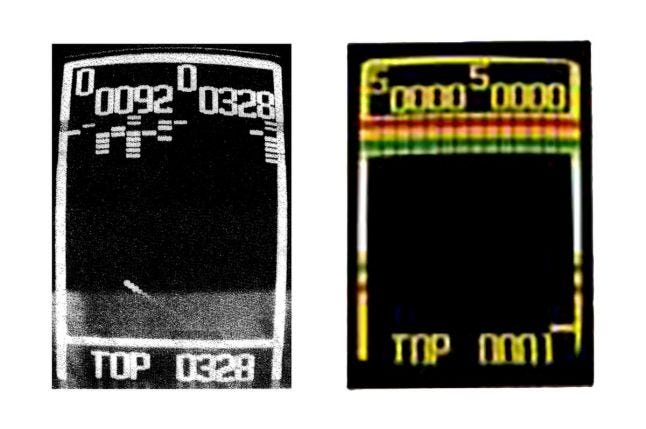

However, “sometimes MAME is wrong,” he admitted. The team at Digital Eclipse discovered a few mistakes in MAME’s code while building out the SNK 40th collection (see slide above), and they also found that even when MAME runs a game without any issues, it doesn't always display it in the best possible light for modern screens.

In closing, Cifaldi encouraged devs to think about rereleasing old games as an educational effort, one that can and should sit alongside work like documentaries and historical works.

“W emake documentaries you play with a controller,” said Cifalidi. “Or if you prefer, we make coffee table books you play on a video game platform.”

And there’s so much more the game industry can be doing, argues Cifaldi, to revitalize old games and present them to the world with well-established vectors for selling and distributing critical deconstruction of creative work.

“We can make a game about making the game,” he added. Referencing Scott McCloud’s comic book about the art of comic books, “Understanding Comics”, he suggests devs should be thinking about ways not just to bring back old games, but to showcase the history and art of game development within the games themselves.

“Usually when we talk about game preservation,I think the notion people have is taking the binary data and making sure its online, safe, or accessible,” said Cifaldi. “Usually what I say to that is: no, the pirates took care of that, we’re fine. But actually, we’ve already lost some games.”

He calls out SNK’s first game Micon Kit as a great example. Released in the late '70s, it’s the game that gave the SNK 40th Anniversary Collection its name, in a sense, but despite loads of work Digital Eclipse couldn’t find a copy of the game’s code.

A shot of Micon Kit 1, SNK's first game (courtesy of Cifaldi's Twitter account)

“Even with the commercial support to make this historical document about this company’s roots, we don’t have its actual roots,” he said. “They seem to be gone.”

He added that Digital Eclipse sent someone to scour Japan for the game code and other SNK historical artifacts, and its only because of the dedicated efforts of collectors and preservationists that the game was able to include so much historical material.

“SNK actually paid him to work with us,” said Cifaldi at one point, referring to a dedicated Japanese collector who helped scan portions of his collection for inclusion in the game. “That should be a standing ovation, but we’re running out of time, so thank you SNK.”

"Steal from work and put it in a box"

“But scariest of all, to me, is source [code],” said Cifaldi. “I’m not shaming companies when I say it’s just the reality: we didn’t hang on to a lot of the source code, and that’s terrifying.”

Cifaldi doesn't have a lot of new advice on this front: he suggested everyone go back and watch the game preservation talks given by Laine Nooney and Jason Scott at prior GDCs, then get busy taking game preservation into their own ahnds.

“Steal from work and put it in a box," he shouted. "I don’t care if you put the box at work or you bring the stuff you stole home and put it in a box, but do it.”

Cifaldi called on devs to not just steal from work and save it, but to ship it to video game preservationists at places like The Strong Museum of Play, the National Videogame Museum, the Internet Archive, and (of course) the Video Game History Foundation.

Also, “the Library of Congress we don’t normally talk about, but they do have an archive in Culpeper,” he added “It’s actually for film, but they also accept code...I’ve talked to them about it and they’re like ‘yeah we’ll take source code, we’ll keep it safe.’”

Also, he added that the Video Game History Foundation will be opening a video game history reference library in the near future. “It may be the first library dedicated to that, but if I’m wrong, if there’s another library dedicated to referencing this stuff, let me know -- I’d like to visit.”

“I think one of our best functions in the world is to provide an impartial voice for efforts like this,” said Cifaldi. “So if you have some video game material and you don’t know what to do with it, I’ll help you go through it and talk through your options.”

“The industry sees source material as a trade secret,” he concluded. “We think it’s an educational tool...it’s kind of a new concept, source code as an educational resource. We’re trying to figure it out, but it’s all brand new and we’re figuring out how to do it as we go."

Read more about:

event-gdcYou May Also Like