Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Devin Wilson sees the (apparent) failure of Sportsfriends as a larger trend in antisocial gaming, including Zynga's latest effort on Facebook, The Friend Game.

Hipster Shit

“I've always thought that Joust thing looks like boring non-game hipster shit.”

That was someone’s comment on a forum thread created to promote Sportsfriends, a collection of games (including J.S. Joust) that has an active Kickstarter campaign as of this writing. The thread was started not by someone involved in Sportsfriends, but by a user of the website who was baffled by the lack of funding being sent the project’s way. I know about this thread because I was ready to start one of my own. I’m not affiliated with any of the Sportsfriends folks, but I’m compelled to support their work.

J.S. Joust has been an incredible phenomenon, but also an oddly inaccessible one. As someone who has yet to have the opportunity to experience it myself, I’m among the many people who have spent vastly more time reading and hearing about J.S. Joust than playing it. It’s probably the most popular game that the fewest people have played, but now that there is a viable path to playing it (along with some other fascinating games), the interest level is disturbingly low.

As is to be expected from the internet, the aforementioned forum thread has produced a number of unreasonable responses. However, alongside these responses are different, more intelligible objections to backing Sportsfriends, the most notable of which is that people simply don’t play local multiplayer games anymore.

I think it could be a wise decision for some of those games involved in Sportsfriends to offer online play or computer-controlled opponents. The games other than J.S. Joust could realistically have these features implemented (given the necessary resources), but I completely understand why these games are presented as featuring local multiplayer only.

The Sportsfriends crew wants to bring people together through video games. I think what we’re discovering, however, is that the market isn’t interested in that. It may be that the average gamer and perhaps even the average internet user are both interested in the opposite. I think the Sportsfriends crew and I would agree that this is a tragedy, and I don’t consider that an exaggeration given the history of play.

The spirit that the Sportsfriends package is trying to highlight is the one that defined gameplay for all but the past 30 years or so. Yes, there have been non-digital single-player experiences throughout history, but games–by and large–were collaborative, social experiences (even at their most competitive). It seems like people just don’t want that anymore from their games, though.

It appears that Sportsfriends may have been fighting an uphill battle from the outset. In its very title are two concepts that the gamer is averse to: sports and friends, and I don’t mean this as a cheap insult.

Non-Gamer Shit

If you enjoy sports video games, you’re not considered a real “gamer”. Only obsessively killing animated characters counts as playing games in our culture. Nevermind the dexterity, strategy, and focus required for mastery of a game like NHL 13, it just doesn’t have enough killing to count as a game. There’s too much emphasis on teamwork (even if it’s virtual teamwork) and not enough emphasis on fighting (not that it’s entirely absent). We can consider winning the Stanley Cup “beating” NHL 13, and this climax is followed by an animation of the customary handshake line between opponents. One side is very disappointed and the other is elated, but overall it’s a civil resolution. Compare this to beating most other video games, in which an uncompromisingly evil being (the likes of which has no real-world analogue in the slightest) has been destroyed and hundreds (if not thousands) of corpses lie in the hero’s wake. Which one of these do we typically celebrate, again?

Finally, the “paid roster update” economic argument that is commonly levelled against sports games holds no water when compared to the actual games in question or, more importantly, “legitimate” gamer pastimes. Buying a new EA Sports game once a year is cheaper than a 180-day Game Time pass for World of Warcraft, but it would be anathema to gamer culture to suggest that World of Warcraft is a waste of money, lining the pockets of exploitative game developers.

Speaking personally: one of my favorite things to do in games is to try and put a virtual puck past a virtual goaltender. It’s offensive to me that this is considered a lesser gaming activity than dismembering zombies, eradicating entire civilizations, obsessively collecting equipment and money, shooting “terrorists” in the head, or even jumping on Goombas. There is a serious lack of critique of violence in games, even though non-violent games like Tetris have historically been very successful.

Furthermore, if the sort of episodic arcs of game narrative that emerge from sessions of sports games, traditional games (including sports themselves), and the titles featured in Sportsfriends continue to be ignored in favor of progressive, plot-driven structures, we will (or already have) found ourselves in a poverty of true play. Too often, play in modern games feels like work. As has been lamented by Steven Conway, we’re simply not given permission to lose in games anymore. The paradigm of contemporary single-player computer game progression is “win, or win later” and the reward is not a “well-played game” (to borrow the title of Bernie DeKoven’s book), but an immutable experience handed down from the game developers. It is this kind of game that is a “boring non-game” if anything is to be attacked as such.

Social Shit

As to the aversion of gamers to friends, this is something that I don’t even need to prove myself. Gamers’ assertions that local multiplayer is dead is an endorsement of such an argument, but it’s not that gamers don’t prefer to have friends.

What seems more correct to say is that gamers like to “have” friends. They like to possess friends as objects, particularly objects in a database. This isn’t exclusive to the kind of “gamer” illustrated in my previous argument, either; this extends itself to many more people than the stereotypical gamer. While we can definitely see this trend in “hardcore” gamers’ tendencies to want friends primarily as cannon fodder or leaderboard entries to surpass, the “casual” gaming space is no stranger to such a phenomenon, and what better way to discuss friends in games in 2012 than by way of the 2012 Facebook game, The Friend Game?

The Friend Game (currently in beta) is the first game from Zynga New York, and–much like its reviled cousins–it essentially asks you to treat your friends like resources. Strictly speaking, any multiplayer game can be criticized for this, but traditional games make clear demarcations where the game-self begins and ends. That’s part of the beauty of even a violent first-person shooter: we can sincerely want to kill each other in one moment, and then feel something completely different once the round is over. We may understand that the first feeling was wholly dependent on certain conditions, and it has no foundation without these conditions. The conditions in question are the rules and fiction of the game that we were playing together, and these conditions can hopefully evaporate gracefully to allow for healthy social relationships when we’re done attacking one another with deadly weapons.

The Friend Game offers no such demarcation. The game is about the actual people that you have relationships with. When The Friend Game asks you a question, it is not about an avatar, but a human being. That is, a human being insofar as The Friend Game can acknowledge one’s humanity.

There isn’t a whole lot to playing The Friend Game. The primary mode of interaction is answering questions, and there are basically two types of questions in the game: questions about you and your friends, and questions about pictures. Neither of these escape striking me as completely poisonous.

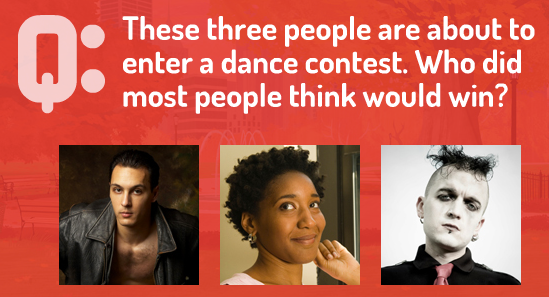

The questions about pictures gleefully perpetuate the worst kinds of judgements: ones based on appearance that are not solely concerning appearance. These picture-questions have two separate components: one aspect is asking players for their opinions and the other asking a single player what he or she thinks the popular opinion among other players is. Depicted below is the latter.

Dancing skill is a relatively innocuous conclusion to draw from a set of photographs, but it is not without harm. These three people exhibit very different visual characteristics, and–unlike similar sociological studies that can be done responsibly–there is no space afforded for critical reflection on one’s adherence or nonadherence to superficial cultural biases. If you answer this question correctly, you are unflinchingly rewarded by the system for your mastery of and subscription to stereotypes.

It goes without saying that the best way to judge who would win a dance contest is to see the contestants dance. Anything else is presumptive, and all we need to do to highlight the offensive nature of The Friend Game is to retain the same structure while offering a different question. Who of these three is most likely to kill someone? Who is most likely to be unemployed? Who is most likely to be HIV positive? Who would you trust most with your children? It’s the same jumping to conclusions, just with different stakes.

The game’s effort to define the personalities of you and your friends is also incredibly disconcerting. Having only gotten to Level 3 myself, I’m still being teased with the “Unlock your Personality Type at LEVEL 5” message, which obviously acts as the carrot-on-a-stick for an unsuspecting user, who is being preyed on for their insecurity regarding their identity.

The game constructs a personality based on a number of characteristics, and gathers information for such a construction through its questions regarding specific people. Many of the game’s questions are about your own preferences, or what you judge your friends’ habits to be, and–based on your answers to these questions–certain characteristics may increase for the person in question.

The questions tend to be very consumeristic in nature, which is reflected in the absurd progression structure of the game. At level 1, you and your friends are standing around in a public park. Levels 2 and 3 are a café and restaurant respectively. Clearly, better friendship (or friend-gaming) is tied to more expensive habits.

Once you’ve upgraded yourself to level 5 (which I can only assume is accompanied by an Apple Store or country club setting), you can finally understand your personality. Judging from the questions I answered, I expect my personality will largely be based on my willingness to precisely calculate tips, follow the rules, get a date, be a strict parent, win on Survivor, watch TV, send text messages on an iOS device, watch The Avengers, be professional, and–of course–be prepared for a zombie apocalypse. This final example earned my friend a point under “practical” when I answered that, yes, he would probably fare decently well in a zombie apocalypse.

Other than the absurdity of zombie preparedness being labeled as “practical”, the most impressive thing about this system is its eagerness to define people by means that only serve to alienate us from each other. The Friend Game largely becomes an exercise in promoting marketing rhetoric and an introverted critique of your friends’ mundane tendencies. What’s worse is that the game presents your friends as loving this dehumanization, giving them an on-screen presence that reacts with ecstasy when the game says “You changed your friend’s personality!”

Peoples’ personalities are determined by the game’s algorithm, and there is no buffer given between the game-self and the real self. We’re taught to understand ourselves by means of Facebook logic and the parameters of The Friend Game, and our on-screen representations seem to love it. The bribes of in-game currency and Skinnerian progression certainly don’t do anything to dissuade us from defining ourselves through such unhealthy trivia, either. And, of course, The Friend Game utilizes the tried-and-true method of “social games... destroy[ing] the time we spend away from them” as Ian Bogost correctly argues.

The genre identifiable as “social games” mostly includes games that are, in fact, antisocial (a quality shared by the video games most “gamers” approve of). In a recent Kotaku piece about the game, Creative Director Frank Lantz reported that the game is “testing how good you are at putting yourself in the shoes of another human and knowing who they are and what their likes and dislikes are.” This statement is dishonest, at least in its first half. The game asked me about my opinion of my friends, not how my friends feel. The Friend Game does not put you in the shoes of another human, but rather asks you to inhabit something more akin to the algorithms of Facebook’s advertising apparatus. Everyone’s personality becomes determined by consumeristic likes and dislikes, rather than something more fundamentally human.

“Does your friend suffer from fears of old age, disease, and death?” is a question that The Friend Game would never dare ask, because the answer unites us rather than divides us. The Friend Game is far less a game than it is a social anxiety generator. It will mostly serve to make us (continue to) worry about what our friends secretly think about us and our patterns of consumption. It aspires–as a perfect microcosm of Facebook–to manage not just our relationships but our very sense of self.

Tough Shit

Sportsfriends is offering a number of truly social experiences, and the general gaming community seems not to be supporting it. The projected failure of Sportsfriends (according to Kicktraq.com and my own suspicions) is a confirmation of the historical transformation of the gaming experience. Grandmothers playing cards around a kitchen table are not considered “gamers” and, to the delight of gamer culture, they will be dead sooner than later.

Playing games is now an individual, consumeristic pastime. There is a lot of potential in the single-player experience and there exist a number of triumphs of that form, but Sportsfriends, which is easily identifiable as an earnest attempt to advance the local multiplayer experience, looks to be rejected by gaming culture. J.S. Joust is apparently just a cute novelty to be remembered fondly as an accessory to certain events; it’s a little too meaningfully social for people who play games in the 21st Century to feel comfortable investing in.

“I've always thought that Joust thing looks like boring non-game hipster shit.”

J.S. Joust is nothing if not a game. It is the complete opposite of a non-game, but a perversion of terms in the past decade or so has made the above sentiment less surprising. J.S. Joust is revolutionary by being conservative: it is a pure game, devoid of fiction or spectacle (other than the admittedly impressive glow of PlayStation Move controllers at night). It offers no screenshots, no pre-order bonus weapons, and no sexy women or tough men in its packaging. It lacks all of the signifiers that gamers crave in their consumption routines.

Ultimately, Sportsfriends is a radical, prosocial gesture, and we can now see that gamers aren’t interested in true games or real people any longer.

Feel free to prove me wrong.

Edit: Thankfully, I've been proven wrong (to some extent)! Sportsfriends got a surge in funding in its last few days.

You May Also Like