Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Religion occasionally gets some lip service when games attempt to flesh out a world, but the deeper issues that guide people to their faith are rarely explored in games. churches, heroes, and gods within are treated in a purely utilitarian manner.

The banner stretched over the entrance to Bioshock’s Rapture, “No Gods or Kings, only Man,” makes for a good descriptor of most modern games. Games are spaces where any “Gods” that show up are just a name, a boss fight, or a battery for the player’s magic. Protagonists aren’t accountable to any “King” either, nor are they really subject to the rules of any kingdom. There is only “Man” and his unlimited influence in the world. In the real world, religion and politics permeate every layer of society. Every human interaction is touched by spirituality or by a social power structure. More importantly, religious and social institutions are responsible for shaping morality. While the approach of games to politics is sometimes shallow (Mark Filipowich, “Existing Above the Law in Video Games”, PopMatters, 4 September 2012) or sometimes deep (Sean Sands, “A Narrative of Crusader Kings”, Gamers With Jobs, 27 June 2013.), they still most often remain trepidatious when approaching religion.

Jordan Rivas doesn’t mince words in his article “The depiction of religion in games is awful for non-religious and religious alike” (Nightmare Mode, 19 November 2012). Rivas argues that most religion in games is reduced to watered down, insubstantial kitsch to maximize profit and minimize thoughtful but potentially offensive content. Games based in the real world keep mentions of God or religion to a minimum or abstracted enough that their representations can only be vaguely associated with real world religious organizations or beliefs. In fearing spiritual content, games ignore what is for many people a major factor in developing a sense of right and wrong. By neglecting these institutions, games fail even to critique religion or spirituality—that would require interacting with the subject matter.

This omission isn’t just a missed opportunity to speak to how people relate to the divine (or how they reconcile a lack thereof), it makes it harder to relate to a game world. Religion and faith attempt to address the anxieties that exist in the human ability to plan and the knowledge of death. The conflict between planning for and fearing the future is central to the human condition and for eons faith has both succeeded and failed in addressing it. When games fear these ideas, they deprive players of potentially meaningful experiences. When players die, resurrection is no more than a button tap away, any gods that exist have no power over the player.

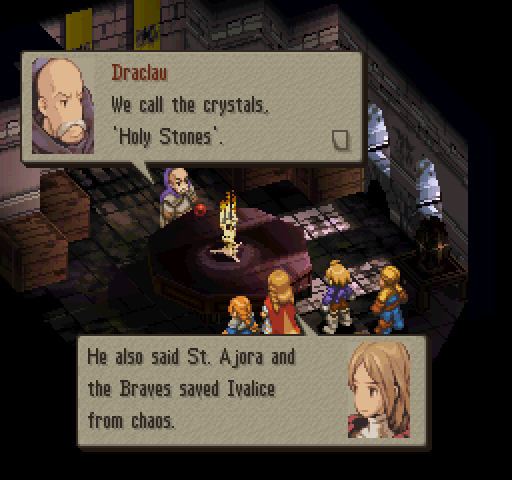

Video game characters don’t ever worry about their immortal souls, and they never seek or struggle against their religious heritage. Apathy is a default condition, and it isn’t even an active choice. Games are more than capable of inventing interesting worlds. In fact, their structure often necessitates it (Nick Dinicola,“To Build a World or Tell a Story?”, PopMatters, 21 May 2012). Religion occasionally gets some lip service when games attempt to flesh out a world, but the deeper issues that guide people to their faith—the quest for meaning in the universe—are rarely explored in games, nor do games explore the ways that religious figures and institutions are able to harness their influence for good or for evil. Game worlds operate in systems of miracles, but churches, heroes, and gods within them are treated in a purely utilitarian manner.

Even in games in which religious figures are supposed to be significant to certain characters and worlds, these figures are robbed of their spirituality. Gods in God of War are just bags of meat waiting to be skewered. The Maker’s existence in Dragon Age is self-evident. His avatar in Thedas, Andraste, is indisputably real. Her remains can (in fact, they must) be located by the player’s party, and they have observably holy effects. These kinds of Gods aren’t any different than people in the universe. They don’t exist outside of it, and they’re subjects to its rules. There’s no mention of faith. Deities aren’t even really deities because they have a material existence and a direct influence on the world. The focus on these kinds of fantasy gods is on how they directly impact different people’s living conditions. Games don’t have anything to say about the purpose of existence or where humans fit in the universe. The existential questions and answers posed by religion and belief rarely make their way into games. Gods and churches are just obstacles or assets.

It’s a problem that’s inherent in power fantasies. Most games create a space where the player has ultimate influence on the world without being accountable to anyone else in it. While I don’t mean to call for the abolition of power fantasies, it becomes a problem when almost the entire medium is based on a fantasy that the isolated, agnostic, spiritually indifferent hero is the ultimate moral authority. If nothing else, religion has a very real impact on people’s lives on both personal and sociological levels. It’s pretty unrealistic for games to avoid addressing those influences so adamantly.

Originally posted on PopMatters.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like