Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

There's no escaping J.K. Rowling's bigoted views and the shadow they cast on Hogwarts Legacy.

The marketing and release of Hogwarts Legacy have left fans and journalists who support trans rights in an uncomfortable position. Though the game's creators aimed for inclusiveness in their character creator and the inclusion of a transgender woman in the cast of NPCs—doesn't purchasing the game fund Rowling's recent turn towards anti-transgender activism?

Many players and developers have said "yes, absolutely. Purchasing this game and supporting Harry Potter is a win for Rowling's hateful cause."

But others among the development and media community have pushed back—even those who support trans rights. A common argument among this crowd is this: though Rowling herself is bigoted, a large number of Harry Potter fans are not (in fact many in the Harry Potter community have been pining for queer and trans characters for years).

The argument goes on to say that Rowling may legally own Harry Potter, but she doesn't own its cultural impact or our relationship to the Wizarding World.

I have a different question: does that argument stand up to scrutiny?

First, some table-setting. In case you aren't aware, Harry Potter creator J.K. Rowling has loudly and proudly expressed her opposition to transgender activism, particularly when it relates to transgender women in the United Kingdom.

The root of her bigotry seems to stem from transphobic talking points that transgender women are not women (she leans on the phrase "identify as a woman" quite a lot), and that women's organizations providing social services to them endanger cisgender victims of sexual and domestic abuse, despite data showing that trans women are disproportionately quite likely to be victims of abuse.

Not content to just have incorrect and bigoted opinions, Rowling has gone on social media to mock trans activism and express support for vocal transphobes.

Her opinions are not merely a question of personal beliefs. In 2022, Rowling began funding a women's shelter that denies access to victimized trans women. She has openly praised the founders of the UK group LGB Alliance—a same-sex rights organization that was founded in opposition to LGBT advocacy organization Stonewall for its support of transgender rights.

She performs this anti-transgender activism not just in a global context of right-wing scapegoating of trans people, but in a local one. She has voiced opposition for Scotland's Gender Recognition Act, saying that it will "harm the most vulnerable women in society: those seeking help after male violence/rape and incarcerated women."

After the law passed Scotland's parliament, the ruling Tory party in the United Kingdom exercised a rarely-used power to overrule the newly-passed legislation.

Rowling's behavior extends to her interactions on social media, often with former fans. She has responded to criticism of her and Avalanche Software's Hogwarts Legacy with extreme vitirol, exposing critics' accounts to waves of attacks by transphobic trolls.

Though Avalanche has stated that she did not work on the game, her direct intervention against those calling for a boycott is a strong reminder that though Rowling is not on the immediate financial food chain, her relationship with Warner Bros. Games owner Warner Bros. Discovery is one that gives her incredible control over how it adapts her books.

If you are familiar with Rowling's public descent into anti-transgender activism, none of this is new to you.

So why are players and developers still interested in playing a Harry Potter-themed game? Well there is plenty of precedent for continuing to play games/read books/watch films made by creators with morally fallible or bigoted views.

In the world of video games, players have had to wrangle with how Minecraft creator Markus "Notch" Persson became a transphobic online crank before selling Mojang to Microsoft. The release of Shadow Complex in 2009 raised questions about the involvement of author Orson Scott Card, who has been publicly homophobic over the years.

This is in addition to the many public game development figures that have played key roles in major franchises before facing sexual harassment or assault accusations.

How we respond to the works of those creators today is an ongoing conversation. Just like with Rowling, plenty of players find comfort in enjoying the work but condemning the artist—they make an effort to reclaim these creations and rid them of their awful baggage.

But Rowling's activism presents a new challenge for the video game industry—because she has worked very hard to make sure such reclamation isn't possible.

As mentioned, Rowling is not the first creative force who has made world-altering work while espousing vile beliefs.

She's also not the first multimedia creator whose work has spawned an international fandom with a parasocial relationship to the source material. Though video games are more popular than ever, we need to look back to the worlds of literature, film, and television to make worthwhile comparisons.

For instance, the fan relationship with the TV franchise Star Trek defies any easy categorization. If it weren't for fans falling in love with the series and passionately pushing for its renewal, it would have been a fascinating artifact of Desilu productions. We'd be writing articles like "hey remember that time Lucille Ball produced a science fiction show?"

For over fifty years, Star Trek fans have written fanfiction, made fan films, dressed up in cosplay, and dreamed about their lives in Starfleet or the Federation. The philosophical question of "who owns Star Trek?" is vague because though Paramount has the legal rights to the series, creator Gene Roddenberry has passed away.

Even when he was alive, the influence of other creative minds shaped the franchise in so many different ways that you can now make self-referential comedies about all the weird directions the series has taken.

Author Anne Rice reinvigorated the vampire genre in the 1990s with her book Interview with the Vampire and spawned a diverse, international fanbase. Rice is a fascinating case study in how fans relate to a work and world, because she was one of the few creators who fought against this parasocial paradigm. She fought fanfiction at every turn and was a notoriously difficult creative partner when the critically acclaimed film starring Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt was in production. (But to contrast Rowling's behavior, she was incredibly supportive of her LGBTQ readers.)

And then of course, there's Star Wars. I am one of millions of Star Wars fans who built my own relationship to George Lucas' world thanks to the neverending parade of books and games that filled the gap between the original trilogy and the prequels.

Lucas and the metaphysical ownership of Star Wars have faced many different kinds of scrutiny over the years—especially after the creative choices he made when directing the prequel trilogy and remastering the original films. I remember going out of my way to volunteer at a film festival in 2010 to see The People vs. George Lucas—a comedy documentary that grappled with the philosophical question of "who does Star Wars belong to?"

For many of us, these were the real Skywalker successors.

None of these stories are morally perfect works made by morally perfect people. Roddenberry, Rice, and Lucas all made huge creative and inclusive strides when telling their stories, but they also made some fundamental mistakes too.

Star Trek's big progressive swings often ran parallel to some awful, retrograde misses. Lucas found himself stuck in the swamp of racial stereotypes when creating new alien creatures in the Star Wars prequels. Anne Rice faced more criticism for the quality of her writing than any of her portrayals, but her litigious response to earnest fanfic writers may have stepped over the line.

Of the three, Lucas is the one who exerted the greatest creative assertiveness over what was "true" and not true about his stories. He has a fascinatingly complicated relationship with the "Extended Universe" that I was so attached to, and until he sold Lucasfilm Ltd. to the Walt Disney Company in 2012, he aggressively fought to maintain ownership of the Star Wars copyright while negotiating with distributors like Fox.

In a modern world with imperfect copyright laws, his push to keep legal control of the films is a huge win for the individual filmmaker.

These are major franchises (hate the word but it's the best I've got) where questions about "who do stories belong to?" make plenty of sense. Even ignoring the death or legal unshackling of these creators from their works, there are decades of push and pull between them and their stories, and each of their shifting relationships with said stories has given way to new status quos.

When talking about these stories, and the flaws they embody, saying "the fans own the story in the creators don't" is an argument with grounding.

But again, that's not true with Rowling.

For the solid decade of publishing Harry Potter books, Rowling had it pretty good. She wrote the books, signed away the film rights (with a healthy degree of creative oversight), and became so rich she managed to downgrade her wealth status by dumping tons of money into charity.

Things started getting weird after the series wrapped up. Fans eager for gay representation in the series wanted to know if anyone was gay. "Yes," Rowling proclaimed one day in 2007. "Albus Dumbledore was a gay man."

This revelation felt more groundbreaking in 2007, when we were coming out of the deeply homophobic pop culture era that was the 2000s. But critics also noted this felt off—if Rowling was so insistent Dumbledore was gay, why is this hidden in the books? Why do none of the students appear to be attracted to classmates of the same gender? The romantic interests of Harry, Ron, and Hermione dominate books 4-7, but they never speak of any same-sex attraction among them or their friends.

Things got even weirder when Rowling got on Twitter. Fans wanted to know if there were any Jewish characters at Hogwarts during Harry's time there. "Anthony Goldstein, Ravenclaw, Jewish Wizard," she replied.

That name is...well, very stereotypically Jewish. And just like Dumbledore's sexuality, it's not a form of representation from the text—it's from the word of the author. Critics have also gone back and forth over whether this name and others like Seamus Finnigan and Cho Chang are stereotypical for their respective ethnic backgrounds.

Outside of the names, Critic Gita Jackson recently catalogued on Twitter that Rowling's broader decisions in Harry Potter worldbuilding have baffling and insensitive real-world implications (Ireland is governed by the British Ministry of Magic? There's only two magical schools across the entire continent of Africa???)

Side note: if you pore over Rowling's work in her post-Potter detective books called The Cormoran Strike series, you'll notice that she really does have a weird habit of shoving characters from non-white or non-British backgrounds in stereotypical boxes (seriously Rowling why are you doing this it's so painful to read).

But before Cormoran Strike, Rowling built out her Potter Empire with both of Universal's theme parks and a new prequel film series from Warner Bros: the Fantastic Beasts franchise. She's even got a screenwriting credit on these projects—not an unusual thing to see for authors whose works are adapted, but it's another stamp of her creative authority, and was even a marketing point back when the first film came out.

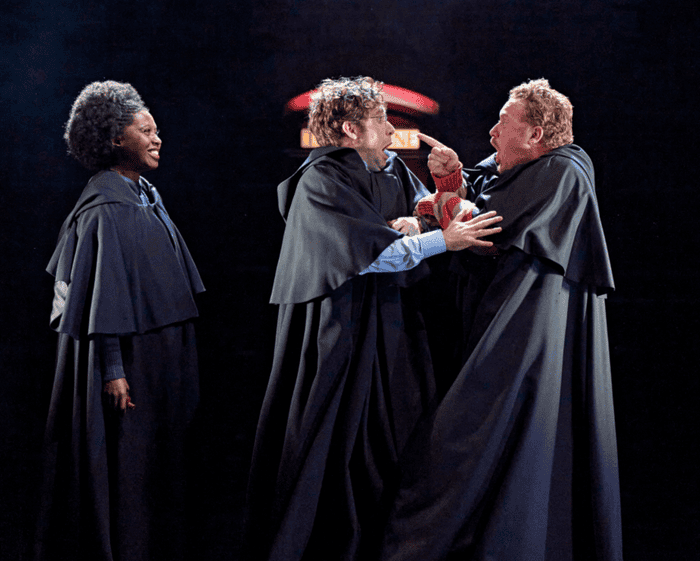

She also spearheaded the production of a major West End production of a "sequel" to the Harry Potter books: Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. Again, her creative blessing was a selling point, and her authority a key one when Noma Dumezweni actress was cast as Hermione Granger. Racist fans got weird and began hurling abuse for casting a black woman in a role previously played by Emma Watson, who is white.

Harry, Ron, and Hermione in the current London production of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. Image via HarryPotterThePlay.com

In an interview with The Guardian, Rowling praised Dumezweni as being "the best actress" for the part, but also went out of her way to explain that the text of the books supports the idea that Hermione could be black. (The character's skin color is barely mentioned in Rowling's books.)

But even in that (progressive? open-minded? I don't know what adjective to use here) decision, there's something weird about her logic. These are creative adaptations—loads of changes are already being made, and for better or worse you could radically alter the backgrounds of anyone from Voldemort to Potter himself.

Rowling's logic isn't "it's an adaptation, I liked the creative direction they went with it." It's "the actress is the best one for the part, and this version of the story fits into my vision of the world." It's a subtle distinction.

For all parties involved, there are huge business benefits to her making this part of the play's press blitz. To get the attention of Harry Potter's global audience, you want to sell the authenticity of the experience as hard as you can.

Rowling's made a business of that authenticity and succeeded in a way that surely has made Lucas somewhat jealous with envy. She signed legally savvy deals, constructed creative partnerships, and even when the product was critically panned, she could at least go home saying "that's true to what's in my head."

I praised Lucas for keeping control of Star Wars, and I suppose I should praise Rowling again for achieving a similar feat.

But Lucas did not go out on a campaign against transgender people. Rowling did. And now their paths diverge.

Rowling's behavior has made things quite clear: it is her stamp of approval that determines if something is "Harry Potter" or not. And the marketing for Hogwarts Legacy sure seems to imply it's got the Rowling blessing.

How much was Rowling involved in the making of Hogwarts Legacy? Allegedly, not that involved. But it's built on the bones of all the other work she's already done. The brand recognition heavily builds on the visual language of the films. The story points draw on her worldbuilding and assertions about where the Wizarding World comes from.

How much money will Rowling make from the game? The terms of her licensing agreement with Warner Bros. and Portkey Games are not public, so we don't know. But she will make money as long as the Harry Potter brand remains visible in the public eye. Warner Bros. Discovery is already publicly stating its intent to cash in on the brand at the blockbuster level, even if the Fantastic Beast films have puttered to a slow stop.

And how might the Harry Potter brand remain visible? Well...try a big blockbuster video game laser-aimed at a generation of fans who once fantasized about receiving an acceptance letter to Hogwarts.

This is a dream moment for many people my age.

The link between the game and Rowling's financials have been spotlighted by plenty of other savvy critics. In response, there have been calls for boycotts of the game, and some outlets like Gamespot have downplayed traditional review coverage in favor of spotlighting Rowling's bigotry (and donations to trans-supporting causes).

I find the release of Hogwarts Legacy to be something like a thunderstorm. Millions of dollars in marketing have been spent on this game. Its development has been fully funded and the developers who worked on it paid. It is an event, not a moment that can be stopped by individual action.

The impact of the boycott is more likely to be a longer-lasting affair, with snowballing consequences for the Potter brand as time goes on. The game's success or failure is largely not in the hands of those abstaining from playing it, but choosing not to purchase it out of protest is a strong moral stance.

What remains then is how any of us as organizations or individuals grapple with this reality. I'm personally not buying or playing the game. My disgust for Rowling's behavior casts a long shadow over any enjoyment I might have on the grounds of Hogwarts.

Some who share my disgust are trying to navigate it by thinking of the Wizarding World as something Rowling doesn't own. And given other examples of how we navigate art and the views of artists over the centuries, I understand how they've reached that conclusion.

But I fear to do so is to play right into the calculus Rowling has repeatedly made. She has worked to control her fictional world. She has shared her views and activism publicly while knowing the risks it could do to her brand. She's written that while she faces public criticism for her views, she's received an unending wave of emails in private thanking her for her statements.

Rowling's universe does not belong to us, even if our memories and nostalgia do. That's true in more than a legal sense. In the creative pull between artists and audiences, Rowling might be the only one who's managed to stake such a position.

I don't write this with any sense of glee. My memories of loving Harry Potter aren't just tied to the books, they're linked in with the time I spent playing with friends, being blown away by the seventh film, and dancing at a "Yuletide Ball" in my senior year at college.

I would never throw out those memories, but I have literally thrown out what little Harry Potter-linked ephemera I've collected over the years. If anyone hopes to escape Rowling's control by leaning on those memories—I regret to tell you she will still happily take your money, and use it to support causes that exclude and contribute to the harm of transgender women.

Fan reclamation of fictional worlds is a wonderful theoretical exercise to let us muse about our connection to art. Here, it's a paper-thin shield Rowling can use to rake in cash from fans who dislike her personal politics.

There are lessons here for developers, critics, and players alike. I still find there to be one fixed point in all of this: transgender women are women, and the transgender community deserves 100 percent of our support.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like