Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Simply put, narrative structure is the organizational framework of a story, Setting refers to the time and place over which the story unfolds.

"To achieve in life is A hard story, But that shouldn't scare you."

- Auliq Ice

Introduction

In the last article of the series, we learned what "narrative design" actually is in the first place, how it is different from writing or other design specializations, how it relates to those, and why it is so hard to find at the current time.

If you are reading this, it means you are already familiar with the concept and want to make your move towards this specialization, or are already working in a related field (congrats!) and want to expand your theoretical knowledge. So let's jump straight into it, and start with: Part 2, Setting and tools.

Simply put, narrative structure is the organizational framework of a story (MasterClass, 2021). With the oldest known records in ancient Greece, to Hollywood, many have attempted to define ideal structures.

Setting refers to the time and place over which the story unfolds. Elements of the setting can include things like era, time of the year, time elapsed over the storytime, mood and atmosphere, location, geographic elements, and many more.

But as described by the references in part 1, it is important to take a step away and contemplate story as not only the written word, but as anything perceived by the spectator. We refer to those visual and auditive elements as "narrative tools".

A narrative tool is some device to form a piece of a story in a player's mind. Our narrative tools divide roughly into three main classes: scripted story, world narrative, and emergent story (Sylvester, 2013).

While often used interchangeably, for clarity we will differentiate between mechanical tools or devices, described below, and literary or style devices, described in part four of the series.

Let's have a look at each of the tool categories described by Sylvester.

Scripted Story

Scripted story is the events that are encoded directly into the game so they play out the same way (Sylvester, 2013). Examples of scripted story can therefore be: Authored dialogue, cutscenes, and every single element in which those cutscenes can be broken down. In this case, a direct synonym to screenwriting can be drawn, evoking topics such as camera angle and movement, environment art, dialogue, and so on. Things like quests could be seen as scripted story tools to some degree as they consist of pre-made tasks for the player to follow, however the form in which the player/protagonist carries out those tasks are variable.

For example in Far Cry, the story is guided through a quest system, however most of the story results from player action, such as the order in which quests get carried out, whether an enemy camp gets silently infiltrated or the protagonist runs in guns blazing, a location is reached by foot, car, or plane, etc. World of Warcraft is a more restrictive open-world setting, however here too, it depends on the player how the story of each quest unfolds: whether it was a single hero that defeated the enemy or the effort of a large group, a collaboration between friends or an economic effort to pay for aid, and so on.

I would therefore categorize "quests" as semi-scripted while the tools they consist of on a microlevel, such as the authored dialogue, remain fully scripted.

Soft Scripting

With soft scripting, the player maintains some degree of interactivity even as the scripted sequence plays out. For example, a player may be walking his character down an alley and witness a murder. Every scream and stab in the murder sequence is prerecorded and pre-animated, so the murder will always play out the same way as the player walks down that alley for the first time. The actions of the player character witnessing the murder, however, are not scripted at all. The player may walk past, stand and watch, or turn and run as the murder proceeds. [...] Every scripted sequence must balance player influence with designer control. (Sylvester, 2013)

During the opening tramcar ride in Half-Life, the story unfolds in scenes outside of the tram while a recorded voice reads off details of facility life. The player has the choice of walking around inside the tram and looking out the different windows, but can’t otherwise affect anything.

In Dead Space 2, the player walks down the aisle of a subway car that hangs from a track in the ceiling. As the car speeds down the tunnel, a link to the track gives way and the car drops into a steep angle. The protagonist slides unstoppably down the aisle, and the player’s normal movement controls are disabled. However, the player retains his shooting controls. As he slides through several train cars, monsters crash through doors and windows and the player must shoot them in time to survive. This sequence is an explosive break from the game's usual deliberate pacing. It takes away part of the player’s movement controls to create a special, authored experience, but sustains flow by leaving most of the interface intact.

Halo: Reach has a system that encodes predefined tactical hints for the computer-controlled characters. These scripted hints make enemies tend toward certain tactical moves, but still allow them to respond on a lower level to attacks by the player. [...] Designers use these hints to author higher-level strategic movements, while the AI handles moment-by-moment tactical responses to player behavior. (Sylvester, 2013)

Another example of such guided soft scripting can be found in Bioshock Infinite's companion AI, Elizabeth. The engine uses interest points and smart terrains to guide Elizabeth's actions. Interest points can be placed in different quantity throughout the level in order to define, with a certain degree of randomness, where Elizabeth will move to or look at (Robertson, 2014). Where Elizabeth looks at, the player will most certainly perceive a point of interest as well, due to the drawing power of stimulus crowds(Milgram, 1969).

There are also ways of scripting events which are naturally immune to interference. Mail can arrive in the player character’s mailbox at a certain time. Objects or characters can appear or disappear while the player is in another room. Radio messages and loudspeaker broadcasts can play. These methods are popular because they are powerful, cheap, and don’t require the careful bespoke design of a custom semi-interactive scripted sequence. (Sylvester, 2013)

I see a broken shell and I remind myself that something might have needed setting free.

See, broken things always have a story, don't they?

-Sara Pennypacker

World Narrative

WORLD NARRATIVE is the story of a place, its past, and its people. It is told through the construction of a place and the objects within it. World narrative is not limited to cold historical data. Like any other narrative tools, it can convey both information and feeling. Prisons, palaces, family homes, rolling countryside—all of these places carry both emotional and informational charges. They work through empathy—What was it like to live here?—and raw environmental emotion—lonely, desolate tundra. (Sylvester, 2013)

Richard Rouse III (2016) refers to Sylvester's world narrative as explorative story space. The important thing for this "side content", according to Rouse, is that it has to be completely optional. This allows for different players to find different pieces, and come up with their own version based on that pieces – and when they compare stories later, they will narrate a different experience to each other, increasing their engagement in the work.

figure 1: Rouse, R. (2016). Dynamic Stories for Dynamic Games: Six Ways to Give Each Player a Unique Narrative [Screenshot from Gone Home]. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SsSh62mSPZE

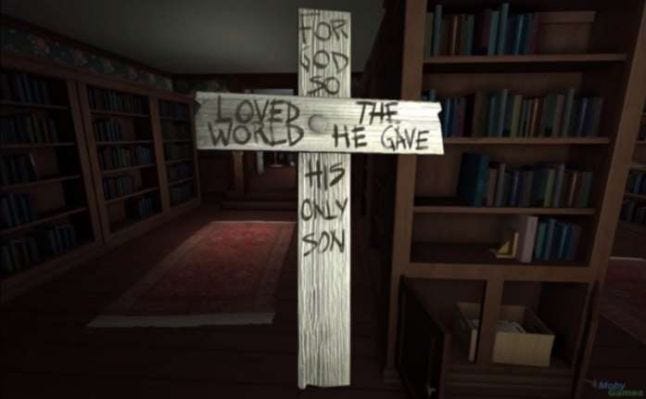

World narrative can leverage cultural symbols to communicate by association. What kind of person do you think of when you picture graffiti on brick walls? Or an igloo? Or a tiny monastery atop a mountain? (Sylvester, 2013)

Just like in the real world, everything in the game world requires a reason to be there, a history. As Behnam Mehrafrooz (n.d.) argues, "The very world of your game itself needs to produce that kind of stuff. A destroyed palace? It can’t just be any ruined palace. It’s got to have a past and a justification to be in ruins, and your level design should reflect that. Have an old knightly order suit of armor? It must have their symbol on it. And also everything else that comes from that order. "

According to Sylvester(2013), "world narrative can also be expressed through documents". He mentions Deux Ex for the use of PDAs, although this method has been exhaustively used throughout the genre, for example in Bioshock Infinite or Borderlands 2. Those PDAs are a very clean and non-intrusive way to include the optional side content described by Rouse(2016), as players can either stop to listen, continue their way without paying attention to the spoken content and opt out entirely, or rehear them whenever it feels comfortable to them.

"One particularly interesting set of PDAs follows the life of a new recruit in a terrorist organization as he travels through the world one step ahead of the player character, on the other side of the law. As the player finds each PDA seemingly minutes or hours after it was left, he comes to know the young terrorist recruit without ever interacting with him." (Sylvester, 2013)

According to Sylvester(2013), "video logs take the concept one obvious step further". They might run in a loop on a screen, or be found ready to be played. World narrative can be transmitted through TV programs, news, propaganda, home videos, camera footage, and so on.

Another mood-setting world narrative can be found in the radios of GTA (or saints row for that matter), or racing games. The feeling transmitted by music and broadcaster tells us about the specific culture of the area that we are located in.

Of course as designer we are never alone, as there is a whole team of specialists, and regardless of the type of project, it will always be essential that everyone on the team understands the "feel" we want to transmit. Take these sets of decorations from GoodGame Empire.

"Lover's Fall", a reward from the 2018/19 valentine's event, creates a strong narrative with just two words describing one asset. Symbolism used here include the pink-purple color, culturally associated to romance, intimacy, passion. Two heart shapes, one forming the trees canopy and the other formed by the twist in the trunk. Roses are a symbol of love in various cultures around the world. Swings evoke distant memories from a children playground and can stand for innocence. Maybe it was a first innocent love? But the strongest sense lies in the story the spectator makes in the mind: Why are there two swings above an abyss? Why are they empty? What came first, did the abyss open from below and took the lives of those two lovers, or was it there from the beginning and represents trust, in other words, holding each other above the abyss? In a more abstract sense, did they fall victims of their own naivety, an innocent first love dragged down by the claws of time?

Figure 2: Lover's Fall. GoodGame Empire. GoodGame Studios.

Few years later, introduce two new versions of the same asset for singles day 2020: on the left the "well of solitude" and on the right the "well of treachery" – but again, the names are the least telling aspect (and definite names are usually defined after the asset is made anyway). In both assets, and even more considering they are usually offered together, we can notice a strong use of symbolism in both shape and color. The first difference that the eye catches is of course the color. The main theme can be found in the color of the well: deep purple for loneliness and desperation, dark red for rage and revenge. The accompanying foliage color is simply due to visual ease (purple and green are part of a triage, red and turquois are complementary). Furthermore, there are at least two heart shapes (one forming the leaves of the twisted tree and another in the trunks shape), reinforcing the notion of an emotional topic. Above of the well, we move from the principal theme to an actual story, told by the artist solely through the visuals of the reworked asset. On the left, a single large swing over the dark abyss. On the right, two swings, one of which hangs from a broken string... the inner string, the one that would be accessible from the other, unbroken swing. Is it the same well that we found years ago? Past the years, memories of innocence have transformed into silent melancholy or even rage against the ever fraying external world in the process of growing up. Maybe even a metaphor for the slow decay of naively absentminded relationships into lonesomeness then anger? The similarity and opposition of love and hate as two sides of the same coin?

I have probably missed further narrative, like eventually the color difference of the trunks, the elements of the tree growing from the top of a rock and leaves of grass encircled by stones, the roses that still climb the trunk, or the weathered path. In the end, every individual will attribute their own unconscious interpretation and sentiments to the same piece of art, and this is precisely what makes world narrative so powerful.

Figure 3: Well of Solitude and Well of Treachery. GoodGame Empire. GoodGame Studios.

At the end of the day, the artist (wether it be graphics, sound, writer, etc) will always know best how to transmit the given narrative.

Citing one artist at GoodGameStudios, the team "would get requests from different departments. Mostly just saying we need a decoration, skin(for a specific building) or a character in halloween theme. Since we already created a styleguide for the visual appearance of this theme we know exactly how it should look like stylewise (some themes are based on a short background story provided by game design). For decorations it is mostly up to the art team to find a interesting narrative. There is always a dialogue with the department who requested the asset to ensure it fulfills its purpose. But there are also a few other cases in which the requests are very specific. For example that the character has to visually look stealthily or sneaky because it has a specific function within the story.

Regarding the arrangement there are different ways to create focal points. The size of the elements/symbol is one way. But also very important is the use of contrast (values, color, saturation, etc.). In our specific case of empire silhouette is an important factor. If a shape looks interesting it immediately catches attention."

Emergent Story

The third and last of Sylvester's(2013) tools is emergent story. Emergent story is the one generated during play, by the interaction of game mechanics and players.

Designers indirectly author a game's emergent story when they design game mechanics. According to Sylvester(2013), "players of Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood have experienced millions of unique emergent stories about medieval battles, daring assassinations, and harrowing rooftop escapes. But none of these players has ever experienced the story of a medieval assassin brushing his teeth in the morning. Tooth brushing isn’t a game mechanic in Brotherhood, so stories about it cannot emerge from that game. By setting up Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood’s mechanics in a specific way, its designers determined which kinds of stories it is capable of generating. In this way, they indirectly authored the emergent stories it generates, even if they didn’t script individual events."

Kaufman(2019) sees the relationship of scripted and emergent story as a virtuous cycle, rather than a straight line: user stories are generated from authored content, which, in turn, can be scripted for reactivity.

Figure 4: Kaufman, R. (2019). Narrative Nuances in Free-To-Play Mobile Games. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ILFzKNLAwVQ

Governance

An iterated game is one that is replayed several times(Shor, 2005). Reciprocity is a term coined by Robert Cialdini(1984), describing the tendency of giving back after receiving.

Based on those two terms, Daniel Cook (2014) evokes "governance", which can be seen as a type of emergent narrative, describing the concept as the political and social structures that emerge beyond the mechanical rules, as seen in Realm of the Mad God and Eve.

Realm of the Mad God is a non-zero-sum game, therein encouraging co-operative play. "Loot stealing" and "free riding" is not an issue here, and in any case the group will be more effective than the individual, thanks to that non-zero-sum nature.(Cook, 2014)

According to Cook, for governance to emerge, the group needs to be more efficient than the individual.

Furthermore, the speaker describes relationships as an iterated game based on reciprocity loops. According to Cook, we can recognize four main factors that contribute to the building of reciprocity loops: proximity, similarity, repeated encounters, and the share of feelings and ideas.

Proximity can be translated as the likeliness of "bumping into each other". Games do this by providing social spaces, where no combat happens and players gather. An example would be in Stormwind's Trade District and Orgrimmar's Valley of Strength in World of Warcraft, or Nosville in Nostale, to name a purer socialite-oriented MMORPG.

Similarity describes the phenomena of friendships emerging from similar groups, which according to the speaker has excessively been researched in children of different social or racial groups. According to the speaker, similarity is an interesting aspect, as we want to force groups to "cross-pollinate", but at the same time, one of the strongest ways of getting people to form groups in the first place is to create similarities.

Cook uses "mafia-esque" to describe the organizations of power that tend to emerge in MMOs. He gives the example of World of Tanks, where players created a huge Skype "Counsel" to sort out issues between clans. According to Cook, we can seed the physics for players to create their societies, but we can continuously tweak this reality to guide society. As Richard Bartle(2006) puts it, designers create the physical reality for players to operate in; "designers need to be considered gods, not governments". Cook concludes his talk recalling his statement from the beginning: "the utopia of the empowered individual is a negative one if we want to create this kind of [autonomous] system."

Following this line of thought, "We can also consider emergent narrative as a technology for generating stories because it creates original content. The designer authors the boundaries and tendencies of the game mechanics, but it’s the interplay among mechanics, player choices, and chance that determines the actual plot of each emergent story." (Sylvester, 2013)

Figure 5: Cook, D. (2014). Governance in F2P Multiplayer Games. [Screenshot from Knights Online]. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8VIlfTtypg

Apophenia

is the human tendency to see imaginary patterns in complex data. We see patterns everywhere, even when there are none. (Sylvester, 2013)

The term Apophenia was coined in 1958 by Klaus Conrad in the book Beginning schizophrenia as the tendency to perceive meaningful connections between unrelated things, referencing Skinner's(1947) term of accidental association.

Matt Brown(2018) talks about projection methods in The Sims. Sims communicate through speechbubbles with mostly random icons and the fictional language "simlish", both of which are abstract enough for players to project any meaning onto it. Another (experimental, not shipped) method he discusses is the placement of censor grids. All those techniques boil down to ambiguity as a capacitor for projected narrative in the spectators mind.

Figure 6:Mullen, L. (year unknown). Simlish: When language and music transcend translation [Screenshot from Stephanie Rose, Youtube]. The California Aggie. https://theaggie.org/2020/11/30/simlish-when-language-and-music-transcend-translation/

Suspension of Disbelief

According to Tynan Sylvester(2013), designers can strengthen emergent stories by labeling existing game mechanics with fiction.

In Medieval: Total War, Every playable character is named and endowed with a unique characterization. Instead of tracking numerical stats, Medieval assigns personality characteristics to nobles and generals. After events such as getting married or winning a battle, nobles can get labels like “Drunkard,” “Fearless,” or “Coward,” which give special bonuses and weaknesses. In another game, a player might lose a battle because his general has a low Leadership stat. In Medieval, he loses because his general had a daughter and decided that he loves his family too much to die in battle. Labeling works because of apophenia. In each example, the emergent story in the player’s mind did not actually happen in the game systems. (Sylvester, 2013)

Abstraction is a higher order type of thinking in which common features are identified (or abstracted) (Alleydog.com, retrieved 2022). Words in a novel can create images in the mind more powerful than any photograph because they only suggest an image, leaving the mind to fill in the details. (Sylvester, 2013)

Abstraction furthermore helps reduce development cost, as in the example of Civilization: Revolution's dancing bears: The player doesn't need to see the bear dancing, the label alone is enough to imagine it, and probably the imagined dance is by far better than anything animated as it is the player's own representation. This way, resources can be better allocated into content that the player is less willing to believe (Meier, 2010)

Jurie Hornemann(2015) borrows the musical term of "diegesis" to describe the balancing of the fictional and mechanical side. According to the speaker, world building is responsible to explain how the fictional world works, physically.

Recordkeeping is a way for games to emphasize emergent stories by keeping records of game events for the player to review afterwards. Civilization IV records borders of each nation at the end of every turn, and when the game ends, the player gets to watch a time-lapsed world map of shifting political boundaries from prehistory to the end of the game. As the map retells world history, it reminds the player of the faced challenges and earned victories. (Sylvester, 2013)

Another prominent example of recordkeeping that at the same time serves a strategical use as diegesis can be seen in many first-person shooter, such as Call of Duty, when after being killed the last seconds replay from the opponents camera perspective.

It's also important to remember it's not about the setting, anyway -

it's about the story, and it's always about the story.

-Stephen King

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like