Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Quick review to the best of my ability the current state of small- and medium-size publishers and publishing deals across the game industry, including terms and advice about how to launch your new indie game.

(note: as always, this sort of business-y writeup is only possible with the help of Finji’s CEO who is the one in charge of all this stuff, including editing this post for me - except for the bit about the “advice yogurt”)

Hello friends! GDC is done finally. Didn’t get sick or exhausted. Learned a lot, as usual. Was lucky to get to see so many friends, especially after the last wild year. I gripe a lot but dream job doesn’t even come close to describing what we get to do here and who we get to work with. It’s absurd how good we have it. And then Night in the Woods won the Seamus McNally Grand Prize. A little on the nose you know.

Anyways, the entire industry continues to change rapidly, especially on the platforms and publishing side of things, where we’re in a particularly chameleonic state at the moment. Which is why I’ve timestamped the actual title of this post. Consider this a sell-by date on this big carton of advice milk. Things are moving quick and you don’t want to accidentally dump a bunch of chunky advice yogurt on your studio froot loops amirite?

Oh and as my wonderful friend George would remind me to state: I am not a lawyer, and nothing in this post can be interpreted as or understood to be legal advice under any circumstances. I’m a idiot dad who makes vidja gams and is two beers down at the time of writing this post already. Not a lawyer.

this.lawyer = false;

Not a lawyer. Not legal advice. Ok. So! Notes on indie publishing! We’ve got a two parter here: terms, and “should I?” Let’s go over terms first so you have a little context for the “should I?” part.

Also, while I help run an indie publisher myself, our docket is full as heck and we are not currently looking to take on any new projects.

Ok!

The terms of your publishing deal are basically your rules of engagement, and while a lot of terms are shared between platforms and publishers in this glorious era, there’s still a few things to keep a close eye on as you get down to business.

Revenue Share

70/30 seems to be the standard pretty much across the board. This means the developer keeps 70% of the revenue, and the publisher keeps 30% of the revenue. This is usually calculated after whatever platform takes their standard 70/30 cut - so you get 70% of 70%. So if you are selling your game through a publisher on Steam for $19.99, you will earn about $9.80 per copy sold, or 49% of whatever your list price is basically. That’s a big slice of the pie, but even if you were self-publishing you would barely even be getting $14 from every major digital storefront, and it’s a heck of noisy market, so yeah maybe it’s worth it to collaborate with the right publisher.

DISCLAIMER: I currently help run an indie publisher, and at the time of writing we’ve never retained more than 15%. This is sustainable but not particularly sexy. We’re weirdos and literally no one else does it this way. That we know of. God it would be fun to be wrong about this one though. Ok let’s keep going.

IP Entanglement

This is an umbrella term that can encapsulate a lot of different legal concepts. The most common one is the nebulous “right of first refusal” on related projects to the one you are signing, which can mean anything from “hey we want first dibs on the sequel” to “you literally can’t even tell anyone else about your future projects until we say you can”. There’s another “right of first something” that sucks either more or less I can’t remember but also watch out for that one.

And then there’s full-on studio-level versions of this, like whatever you make next, sequel or not, it’s ours, deal with it. And the idea behind this is when someone invests a lot of time and money in you, the developer, they want maybe a little edge when you inevitably have this huge shared success together, just in case. Which is pretty understandable, since these investments can get pretty huge. But the downside to this for the developer can be weeks or months of bitter uncertainty and lopsided negotiations that can be destructive to a creative team.

The thing is, if it’s a good collaboration between a good dev and a good publisher, working together on the next thing should happen organically. If it’s not a good collaboration, and people would rather work with other people next time, what, are you actually going to force a deal to happen? Are you out of your mind? Do you enjoy suffering?

On the other other hand, when funding crosses that magic $1m line, investors and publishers tend to want a little bit of insurance on such a big bet. Maybe this is one of the things that can be carefully negotiated in that high-investment case. Otherwise it should get in the sea.

DISCLAIMER: I currently help run an indie publisher, and we have never and will never do IP entanglement because it is dumb.

Funding

One thing we ran into multiple times this month is developer budgets that are too high. Or rather, they will take care of the team that wants to make the game, and they’re very carefully thought out in that regard, but the sales thresholds that the game would have to hit after release are extremely ambitious in the current market.

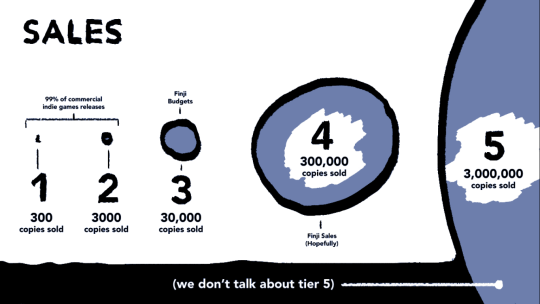

This is a slide we produced for a talk up in Winnipeg on February 2nd, 2018. This is our understanding of the indie games market right now, in terms of relatively full-price-ish, non-bundled, non-mobile, premium games. There’s a bit of elasticity across other markets and models but we’re not gonna go there for now. The point is, most commercial games released this year will never meaningfully breach the 3000 copies barrier.

A spare few will hit 30,000 copies. If you’re selling $20 games, then moving 30,000 copies at full price, which is extremely rare, means break-even cash budgets of $500k USD or smaller. We all hope to get into that 300,000 copies ballpark, but planning your budget around that even more rare tier of sales is a very risky move.

For mobile the math is even more complex - if you don’t get strong featuring in the digital storefronts, cracking that 30,000 copies sales figure is mostly out of your control for a premium game, and the retail prices are much lower.

These are all just things to keep in mind when you’re pitching publishers on your budget. If you ask for $1m USD, not only is it the kind of budget that will likely come with IP entanglement, but they have to do the math - do they think they can hit those tier 4 sales or better? Otherwise it’s a pretty risky move for them.

Recoup

This is a little mini 3-parter, hopefully this doesn’t get too confusing.

Recoup is basically the thing where investors earn their investment back before devs start earning their full revenue share. This can be in the form of a different temporary split (e.g. developer earns 10% and publisher earns 90% until they have earned back their funding investment, then it flips back to standard 70/30) or it can be structured more like a loan, where it doesn’t come off the top but earns higher interest, or it can just be that the investors recoup their funds and bail out (these are particularly nice angels), and so on. There’s a lot of options here.

Recoup on initial investment: the standard model for this by my understanding is that it’s 100% up-front. If the publisher funds your development to the tune of $100,000, they earn that full amount back out of 100% of the sales before they start doing the standard 70/30 split. Maybe not all publishers have to do this because their 30% is worth so much, and I know some other publishers do more of a split during this phase so they recoup quickly but devs have access to some revenue still. There’s a range of things here, but basically it is standard practice for investors to get something like up-front recoup.

Recoup on large expenses: at Finji this basically amounts to things like console ports. Maybe this could be like a ... really nice trailer? Or a tremendous specific merch thing? But since ports run in the low five-figures, they’re pretty substantial expenses, and they contribute to the game’s overall revenue, so we treat these as essentially additional recoupable investments in the project. Everybody chips in and everybody benefits, and it’s treated like extended dev costs basically.

Recoup on marketing expenses: a lot of contracts still have carve-outs for this and historically this has been the place where publishers kind of intensely screw over developers. The idea used to be that publishers would say “well marketing expenses are like ports, they benefit the project, so we treat it like additional investment.” Sounds like a good deal!

Except that every time a developer would check in to see when they were getting their rev share, somehow the publisher still hadn’t quite paid back that marketing expense yet. Just... there were just a lot of marketing expenses, ok? A lot. No, we can’t say exactly what we spent it all on (IT WAS CHAMPAGNE BTW) but there was a lot of those. Expenses I mean.

Soooo the modern version of this is not as bad, but still pretty dangerous. The modern version of this is “itemized marketing expenses”. So the publisher spends a bunch of money making you a huge trailer or doing something else, and then they itemize out your share of those expenses, and only those things can be treated as recoupable. Sounds like a good deal!

Except that things that seem like a great idea during development (a huge booth, a really slick promo campaign, a crazy trailer), sometimes seem like not so great an idea later, especially if you’re not keeping the modern sales market in mind.

So the thing here is two-fold: first, whatever math you’re doing for figuring out that initial investment, do that same math for your marketing expenses because chances are they’re going to be treated like additional investment. And these things can add up fast - don’t be afraid to talk about the details up front.

Second, consider that if a potential publisher is recouping their marketing expenses up-front, then they’re drastically reducing the risk they’re taking on your project. They break even before you do, and then start collecting 30% of your revenue.

Something about that seems off to me.

Track Record

This is a simple one: if you’re talking to an outfit, ask for a breakdown of what percentage of their titles get close to Tier 3 (30k copies) at full price in the first 12 months, and what percentage of their titles get close to Tier 4 (300k copies) at full price in the first 12 months. This should give you a sense of their ability to effectively market a game.

The Machine

Last but not least, if you’re talking to an outfit, ask for a breakdown of their internal PR, production, marketing, and show staff. Who’s writing the press releases? Who’s staffing the booth? Who’s going to be checking in on your schedule? Do they have designers on staff to help kick ideas around? Do they have pinch technical staff who can help get those last couple bugs done before launch?

Find out who you’re working with.

Well maybe after reading all that stuff you already made up your mind, but just in case, here’s some other ways of looking at this problem.

One way of looking at this problem is that we started our own publisher because we wanted to do something that nobody else is doing right now. We have hangups. We have weird ideas about how to approach this thing. So, if you’re us, maybe the answer is no, you shouldn’t get a publisher.

BUT

BUUUUTTTTT

The other way of looking at it is that it took us like ten years to figure out how to do this and not everybody has ten years to fumble around making a weird publishing company for themselves. And our company does a lot of stuff that we consider to be integral to shipping games in the current market: show presence, community management, PR, design mentorship, managing press & platform relationships, development funding, producing console ports, and so on. If you simply don’t do those things, then you may find yourself taking more risks than is strictly necessary. If you delegate your developers to do these things, then in our experience, you get unhappy, burned out devs who are spending more time doing weird publisher stuff than they are doing the thing they’re good at which is making games.

In other words, if you want to mitigate some risks around your commercial game dev, somebody needs to do this junk. Somebody needs to figure out funding. Somebody needs to figure out ports. Somebody needs to say hi to that journalist that loves your game even though it’s not even a prototype yet. And if you make the devs do it, they will crash eventually.

So what are your options? Well, publishers are one option, obviously! But you can also break up these responsibilities. Maybe your art director has a huge following and is a kind of a natural at the whole PR thing in terms of strategy / vibe, so really you don’t even need a publisher or even a PR firm, you need someone to send a bunch of emails around shows and launches. Or maybe you do need a PR firm. Or maybe you have a savvy business half in your studio already, you just need funding - you can hit up banks, angel investors, dev grants, and so on. Maybe you just need a community manager while you’re in Early Access and the rest of your issues will kind of fix themselves. Maybe you need a design mentor. Maybe you just need a porting studio. Maybe you need two of these things and one other thing I forgot.

The point is you can roll your own thing. That in and of itself also takes time, but it’s closer to how I operate as part of a developer and self-publisher: we use a mix of in-house staff, freelancers, and out-sourced work. But maybe even trying to think about how you would start to plan something like this sounds like such a nightmare that a publisher would be a relief just to take on that load.

Different developers need different things, and I can’t end this with some kind of “well, thankfully, all devs can just do ____________ and then everything is good” ultimatum. Just be aware that publishers are there to solve some problems, and they’re not the only way to solve it anymore, even though they are a convenient way of doing that. And should you find a publisher you like, hopefully the terms section above will come in handy as you navigate these weird and unpredictable seas.

Best of luck, and somehow, despite this ludicrous volume of text, this is actually only part 1 of my GDC wrap-up. Part 2 hopefully will be up by the weekend, and is a lot more focused on design, marketing, and pitching.

Hope this helps somehow!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like