Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Would Steam would succeed as a subscription service? You know, monthly payment, access to any games you wanted on Steam, that kind of thing. Would be profitable for the company? For the players? What are the ups and downs of that kind of thing?

[Reposted from my blog - the original post can be found here.]

Preface: this isn’t my idea. It’s not original. It’s been discussed before, by better minds than mine, but I have stuff to say about it. So, here we go:

Today over lunch I was talking with my buddy Shawn about Steam, the social network/storefront for titles by Valve and other games, too. Shawn and I use Steam to play all sorts of games, and consider the Steam interface vastly superior to Windows Live, which does the same sort of thing, but uses that annoying fake currency that so many companies use to psychologically distance you from your money (after all, you’re not spending money, you’re spending Microsoft points! Except, your points cost you money. It’s stupid and works stupidly well, especially on children).

But Steam is useful: it offers a great service for free, and brings me the only targeted advertising I actually appreciate: their weekly video game specials. I don’t mind seeing them, because the deals are so good, and I’ve bought games through their weekend specials more than once.

But as Shawn and I mulled over lunch, we wondered how Steam would succeed as a subscription service. You know, monthly payment, access to any games you wanted on Steam, that kind of thing. Would be profitable for the company? For the players? What were the ups and downs of that kind of thing? How would developers be compensated, especially independent developers?

We got to thinking about it. Obviously, we don’t know the hard numbers, so like all the ideas on this blog, discussion is encouraged, but please, no flames over the hard numbers. Hard numbers are put up to aid in discussion, not to be the singular point of contention.

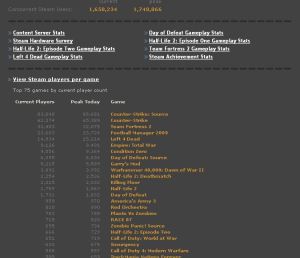

The reason we chose to discuss Steam, instead of Windows Live, or the new (and not yet launched) Battle.net, or even something like XFire, was because Steam already has built into it the core feature that would be needed to properly make a subscription fee work for both players and developers: playtime tracking. Steam tracks how long games are played, both by player and total game time. This information would be key to determining how much a developer made for including their game in this theoretical monthly subscription service. You can see the stats from Steam’s play tracking system here.

Basically, it works like this: Say you have 100,000 users all paying 10 bucks a month for a Steam subscription. Say you also have 4 entities: Steam (Valve), Developer A, B, and C. Steam’s gross take per month is a cool million for all those subscribers. Obviously, these numbers are contrived, don’t reflect taxes, and other costs, I know, we’re just talking, so chill. They take their cut for running the service, 30 percent, let’s say, just like Apple and their App Store, and that leaves 70 percent of that million, or 700,000 to distribute between Developer A, B, and C.

Now, say that Developer A’s game is a First Person Shooter. It kicks ass, and all the kids are playing it, which is great, because Developer A spent a truckload of money making it. Luckily, they made a good game and people want to play it.

Developer B, on the other hand, spent about three days slapping together a crappy puzzle game. It’s awful and no one wants to play. Who cares, right? They spent three days on it.

Developer C created a simple Real-Time Strategy game that has a hard learning curve, so it’s slow to learn, but once players learn it, they have a blast and play it for hours.

So what happens? We take the 700,000 left over after Steam’s cut and split it between the three developers, based on percentage of total playtime. If those 100,000 players spent 700,000 hours (a number we’re picking because the math is easy) playing the three games in the month, then that equals to about a dollar an hour for the Developers. But not all three games were played at the same percentages.

Developer A’s FPS did great in the beginning of the month, then evened out as the month went on. Their Total playtime was 78% of the total game hours spent on Steam that month.

Developer B’s crappy game sucked, so hardly anyone played it. 3%

Developer C’s game wasn’t very popular at first, but as word of mouth that the game was fun and worth a play spread, the percentage rose. 19%

Based on these percentages, the three developers earn for the month in question:

Developer A: $546,000

Developer B: $21,000

Developer C: $133,000

Okay, so these are just throwaway numbers, you say. Fine. Let’s try it with some real numbers, taken from Steam’s website. Also, to make the math easier on me, let’s make some assumptions:

Assumption 1: Let’s use one day, instead of a month, since I don’t wanna do the math for a whole month. This means that instead of 10 bucks to split up per player per month, we have 33 cents per player per day.

Assumption 2: Also, for ease of use, let’s say that each player only plays one game in their playtime in one day, instead of splitting their playtime between games.

Assumption 3: Let’s assume that all users spend an equal amount of time for any game they play, so 1 user = 1 hour. This makes the percentages easier to calculate, and saves me math.

Assumption 4: Let’s limit it to a few games, since I don’t want to do more math than I have to do.

So, here is a screenshot of Steam’s stats page that I took when I was getting ready to do these calculations:

screenshot

This screenshot says that the highest unique users on Steam, at the time I took the screenshot, was 1,748,066. Now, based on our assumptions, that would mean Steam would take in 33 cents per user, so the total take would be 576,861.78 for today for a subscription service.

Less Steam’s 30 percent cut, we have 403,803.25 to distribute between the developers today.

Counter-Strike: Source, 89681 users, 0.051% of the total Steam usage time, or $20593.97

Counter-Strike, 65389 users, 0.037% of the total Steam usage time, or $14940.72

Empire: Total War, 9491 users, 0.005% of the total Steam usage time, or $2019.01

Killing Floor, 2032 users, 0.001% of the total Steam usage time, or $403.80

Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, 597 users, 0.0003% of total Steam usage time, or $121.14

Obviously, these numbers are very rough estimates (due to rounding percentages, and all that noise), and they are also based of playtime on a random Tuesday. Steam numbers probably fluctuate quite a bit, especially over weekends. However, they can give us a few other ideas:

Here are the current prices for these five games on Steam:

Counter-Strike Source – 19.99

Counter-Strike – 9.99

Empire: Total War – 49.99

Killing Floor –17.99

Call of Duty 4 –39.99

We can use these prices to determine the break even number for these games, based on playtime, if we pretend these numbers are good. If developers cannot move this many copies of the game per day, they are losing money by not going with the subscription model.

Counter-Strike: Source needs to sell 1030.21 copies per day in order to break even with what the game would be making via this subscription model. I doubt they are selling that many copies a day.

Counter-Strike – 1495.56 copies per day. I really doubt they are selling that many copies a day, especially for an old game.

Empire: Total War – 40.38 copies per day

Killing Floor – 22 copies per day

Call of Duty 4 – 3 copies per day.

So what do these numbers tell us? Several things, but first, some caveats:

Valve games do better on Steam, because that’s how Valve games are played. Counter-Strike: Source and Counter-Strike can only be played over Steam, so obviously those numbers are going to be much higher, since they represent the total player base for the game (aside from private servers), rather than just the player base that is using Steam to play the game. The data for Call of Duty 4 and Empire: Total War, which can be played without Steam, should be taken with a grain of salt. I don’t have access to the total player numbers of those games separate from Steam. Obviously, those numbers would make a significant difference.

Is this a model that would really benefit smaller developers? Well, it depends on costs. Assuming these numbers were the same for every day in a year (which would never happen, but again, it makes the math easier): a small developer that was able to maintain 500 users a day would make 113.06 per day, or 3391.94 per month, or 41268.69 per year. That’s an acceptable (maybe a little low) salary if you’re a one man shop, but won’t work for even two people. This means that, roughly, you need to command at least 500 users a day per person, in order to be able to barely support a small studio on this model. That’s probably not feasible for a small company, especially one just starting out.

Keep in mind, however, that I went with the low end of the price spectrum in my calculations, at 10 bucks per user per month. I think that users would support more, possibly even up to 25 bucks a month, for all the games they could play. It depends on what the market would allow, really. At 25 bucks a month, that same 500 users per day nets your small company 103171.73 per year, which is much more feasible for a two person (or three person, if you all wanted to rough it and live and work together in the same space, like a rented house or something).

These numbers would probably shift due to players widening their game choices, too, since if players had access to everything for one monthly fee, they would probably try more games. Most people on Steam play Counter-Strike Source because they already own it and don’t have to pay anything else for it. If the cost of playing a new game was nothing more than the time it took to try it out (because they already paying a subscription fee), players would probably try more games, because the psychological “price” is free.

Anyhow, since we’ve already passed the math speculation phase of our discussion and answered our “could this work?” question (answer: possibly?), let’s talk about the benefits and drawbacks of the system:

Benefit: this system encourages game developers to continue to support their games, because more support (new content, community building, etc.) means more playtime, which means a higher percentage of the profits. This also means that companies would be more likely to continue to support a working title than create a large expansion patch and arbitrarily calling it a new game. I’m looking at you, Left 4 Dead 2.

Benefit: this system encourages better games. Games are one of the few marketplaces where better content directly equals better sales. If a huge blockbuster movie comes out over a summer, it will probably recoup its costs, simply because of the economics of film. People will pay to see a movie in the theater, whether it sucks or not, simply based on a huge marketing campaign or established IP. Games aren’t like that, possibly because of their price points, possibly because gamers are sick of getting burned on awful games. Bad reviews can easily kill a game, because many gamers wait for reviews.

Sure, some game companies can sell millions of copies of a game on brand name alone (Blizzard Entertainment), but those companies are rare. How often do gamers buy a game just because EA made it? Or Relic? Or someone else? Almost never. You wait for the game to come out and you wait for the reviews. Fanboys aside, gamers are pretty discerning purchasers.

However, if money made on a game was based entirely on playtime, companies would be much more focused on making good games that kept players engaged.

Benefit: it’s nice to have a budget: Everyone likes to know what their monthly bills are going to be. It makes budgeting easier. If I know I can play any game on Steam for 25 bucks a month, and that’s my total gaming budget each month, it’s going to mean I play a lot more games, a wide variety of games, but also probably spend more time gaming. And since the more time I spent playing the game, the less it costs me per hour (please, no gaming has the hidden cost of wasting time arguments, so does television. we all need to relax sometimes. the method isn’t important), which is great.

Benefit: it’s good for companies, because it encourages them to trim the fat from their business models. If I can release a game on Steam that gets me 100 hours of playtime per month, but costs me 80 of those hours for overhead, I’m going to figure out how to streamline my infrastructure to cut costs so I can net more than 20 hours a month profit. This doesn’t mean cutting quality, however, since I don’t want to drop under those 100 hours a month.

Benefit: it encourages game companies to focus on good gameplay, rather than flashy graphics. Flashy graphics cost a lot, and probably sell games in the “buy a game once” model. However, when profits are about sustaining players, spending the entire budget on flashy graphics and making an awful game means that I’ll see an initial surge in gameplay, but once players realize my game sucks, they’ll stop playing.

Benefit: it keeps games on the market longer. Sometimes I still wanna play Warcraft 2 or Lords of the Realm 2 or Heroes of Might and Magic 3, because those games rocked. Right now, my continued interest in those games nets Blizzard, Sierra, and New World Computing exactly no cash per month since I already own them. If old games find even a small percentage of playtime on the subscription service, companies still make money, even for old games they no longer support.

So those are some of the benefits, what about possible drawbacks?

Possible Drawback: Gaming of the system: companies using botted computers to play their games 24x7 to skew playtime percentages. Sure, this is a drawback. However (and I’m sick of doing math, so I’m just gonna wing this question), I’m not sure if the 25 buck a month investment for the company (to set up a subscription account per computer) would show a return on that investment. Would 25 bucks a month for a subscription (plus computing costs) return at least 25 bucks a month in higher percentages? I doubt it. The numbers just don’t work. Plus, Steam could easily spot accounts that spent 24x7 logged into a game and remove their playtime from the overall monthly percentage. I doubt this would be an issue.

Possible Drawback: more gaming timesinks, ala MMORPGs. Since MMOs already use a subscription service, they are a good place to look for timesinks, and they are full of them. Travel time, cooldowns, raid lockout timers, they use them all to make sure you can’t accomplish as much as you want to accomplish in the game, so you keep playing it. Would all games adopt timesinks to encourage players to keep playing? Possibly.

However, the real question is this: would players put up with it if they can just play another game that’s fun and doesn’t use artificial timesinks to keep them playing? I’m not sure, this is one that would definitely have to be tested. One thing to note, however, is that more content =/= timesink. I hope that developers would simply make more content for their games, instead of more timesinks. Still, it’s hard to know without a test.

Possible Drawback: Wal-Mart syndrome. If Steam is the place to go to play games, then Steam gets to call the shots. Once they become big enough, they can push people around, just like Wal-Mart can push around companies that do business with them. This is a tough drawback to avoid, and I’m not sure how to solve it.

On the other side, a subscription service would only work in Steam had all the hot new games. If a subscription service meant that I would have to wait to play a new game, then the subscription service isn’t worth it.

Possible Drawback: no game ownership. With the current “buy a game once” model, once I buy a game, I can play it forever, as long as I can get it to run on my hardware (Damn you, Vista 64!). However, a subscription-based service doesn’t work like that, even with current subscription gaming models, MMOs. If I stop paying for World of Warcraft, I can’t play the game anymore. This bothers me, because I like to go back and play old games sometimes, and it would be nice if those games were free. There are several options for solving this:

1. Give games an expiration date and after that, make them free. Say that once a game was on Steam for 15 years (or some other reasonable number, we don’t want another Digital Millennium Copyright Act pile of BS) it would no longer require a subscription fee to play. Or better yet, say that once a game was no longer supported, it would become free. Hell, abadonware rules do this sort of thing anyway. This option probably isn’t feasible, however.

2. Give players “unlock a game forever” points after so many months of paying the subscription fee. Just like companies give bonuses for being with them for awhile (I hear employees of Blizzard get a sword after 5 years – that sure beats a crappy watch or a plaque) , let players build up “unlock points” for service. If they decide to leave the subscription model, they can use these “unlock points” to take a few games with them. Think of them like frequent flyer miles or something like that.

3. Continue to allow players to purchase games outside the subscription model. Thus, if Dr. Jack Goobertop wants to play Counter-Strike and doesn’t want any other games, let him buy Counter-Strike. There’s no reason that both a subscription service and a “buy a game once” model can’t coexist, so long as revenues from those who bought the game once, but still played the game online, only came from subscription-based players.

Possible Drawback: this idea won’t work because of the numbers. Yes, that could be a problem, but one best suited toward the financial wizards. Unless you are such a wizard and have all the numbers, shut up. No one knows if this would work until someone tries it.

Anyway, that’s all I have for know. This post is already way too long.

This is an idea that requires more thought, but definitely something to look into. I’m sure companies already are looking for this, including Steam. Why else would Steam already be tracking all those stats?

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like