Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Most people don't care if we almost kill ourselves on the way to making great games; they still judge them entirely on what they play in the end. In this blog, find out why Denki have embraced "busking" as part of developing their latest game - Quarrel.

Source: <a class=

Introduction

What's your job? Seriously - what do you tell people when they ask?

If you tell them "Coder", "Artist", "Producer", “Designer” or whatever else happens to be on your business card I’d like you to have another think, because recent events have convinced me that's almost certainly not what your job really is.

It’s become apparent that many people never consider the connection between the job they do and the value it creates. It seems to be a side-effect of working in organisations; especially big organisations, but it affects small ones too.

It's easier to spot the value in certain professions, of course; if you're a doctor and you cure a patient of an ailment then the real, tangible value of your work is pretty obvious. You're a healer – you’re improving people's lives by healing them; a noble calling for sure.

But jobs like that are becoming rarer as our society becomes more complex and collaboration becomes essential to delivering many of today's demands.

As a result, I doubt many game developers ever have cause to think of themselves as entertainers, but I'd argue that's precisely what we are if we're working in the games industry.

Not artists; or scientists; or technologists or any other "-ist". Not engineers; or managers; or administrators. We might draw on these skills while doing our job, but they are not the actual purpose in-and-of themselves.

We are entertainers - more like a busker on a street corner than a scientist in a lab. But unlike buskers (and just like many scientists) game developers rarely meet their audience face-to-face, and that can have all sorts of unexpected and unhelpful consequences.

The Busking Business Model: Turning Frowns Upside Down

Source: <a class=

When I'm not writing blogs I run a games studio in Scotland called Denki – I say “games studio” so people will know what I mean, but we prefer to think of Denki as a digital toy factory, for reasons I'll go in to another time. Regardless of semantics though, it would be easy for me to think it's enough that our teams have paying work to keep them gainfully employed, and that our costs don't get out of control. That's what a typical “studio manager” does after all, right? Well, that might be true on the surface, but it’s not how I see it.

I recognise the important differences between the mechanical process of managing a games studio and the very real value it must deliver if I'm still going to have a studio to manage tomorrow. My day-to-day decisions must ultimately result in smiles on the faces of the people who play Denki's games, or the rest of it doesn't matter. When it comes right down to it I don't get paid for controlling studio costs, I get paid for turning scowls in to smiles. Setting strategy and managing the studio is just one small part of how I help Denki achieve that aim.

I suspect you get paid for turning scowls in to smiles too; regardless of your specific role in getting a game in to someone's hands. Your job is to entertain your audience which, in this case, happens to be the person playing your game. And, just like the busker strumming their guitar on the street, when your audience appreciates your efforts, you're more likely (though still not guaranteed) to make money.

As a result, the business model for a busker is closer to the business model of an indie game developer than you might first realise. Here's some of the similarities for starters, and I'm sure you'll think of plenty others once you get the idea:

(Go with me on this one…)

We both tend to work on our acts behind closed doors until we have enough confidence in our creation to believe an audience will appreciate it. Or we run out of money – whichever happens first.

When we finally reveal our acts to the world we both have only a fleeting moment to catch people's attention before they decide to give us their time or walk on by.

We both perform to an audience with many other distractions competing for their attention - we have to convince them to give their time to something they didn't plan to.

We both have to make sure we structure our acts so they are constantly engaging – the moment the engagement dips they're off, dragged away by all the other pressing things they planned to do that day; which means we’re less likely to get paid.

Finally, regardless of the objective quality, there will always be those who don't like our act. And despite our best efforts there will also be those who enjoy our acts, but still aren't prepared to pay for them, for whatever reason.

The Power Of The Audience

Source: <a class=

These similarities were all brought home to me in glorious detail last month when we took Denki’s latest game busking.

We’d decided to set up for three days at the world's biggest performance festival: the Edinburgh Festival in Scotland. We wanted to encourage passers-by to play it and provide feedback so we could understand how they perceive our game, and how we could make it more engaging for them. I wanted to count the scowls we made in to smiles myself, and learn what it would take to make more.

As a game developer more used to interfacing with computers than other people it was a daunting experience: to have that fundamental connection between the job I do each day and its ultimate purpose laid bare in the most vivid way imaginable.

I was prepared for the worst; however, having been through the trauma and lived to tell the tale I once again appreciate just how vital this connection between developer and audience is and why we can get things so wrong when we ignore it.

The game we've been working on is called Quarrel. It fits neatly in to the “strategy word game” genre – you know, the one where players compete for territories by trying to "out-word" one another? Yup, thought so. Anyway, it's been in development at Denki for a while now and recently reached an important milestone where it's “showable without shame”; so we thought we'd use the opportunity to take it busking in Edinburgh. Earlier this month, a whole gang of Denkians arrived at the Edinburgh International Conference Centre intent on finding out what the general public would make of Quarrel.

Source: <a class=

We were piggybacking the University of Abertay's most-excellent Dare To Be Digital competition. Seriously, if you haven't heard about Dare To Be Digital yet you really need to check it out because it's redefining the way people learn to make games. And while you're at it, take a look at Abertay's new MProf Games Development course starting this year - if there's a more exciting course for would-be game developers out there at the moment I'm not aware of it.

It was specifically the ProtoPlay part of Dare To Be Digital we were involved with; the part where all fourteen teams put their games on show for the general public to play. Previously the Dare To Be Digital teams had only shown their games to industry experts, but a few years ago they took a bold decision to host a public show as part of the Edinburgh Festival, where members of the public as well as the industry judges would be invited to evaluate the results.

It's no exaggeration to say that the quality of the games almost doubled overnight. Having been involved in judging the Dare To Be Digital games since its inception back in 1999 I could honestly say that none of the refinements they had made to the process made anything like the difference that asking the teams to demo their games to the general public made. And that got me thinking: why did that one change make such a difference? After much consideration my conclusion is that it reinforced the link between the teams and their audience. Further still, it completely negates any sort of rational excuses for weaknesses in the final product.

Industry judges have been there on the front lines – they'll usually understand the feeling of pulling an all-nighter to get something delivered against the odds, and will therefore tend to listen sympathetically to stories of misfortune and good intent from the teams and temper their criticisms accordingly.

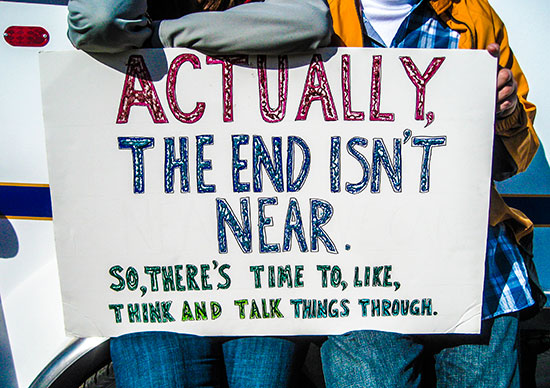

The general public however, and especially children, care not for any heroic development efforts, whether successful or not. Unlike industry judges the public evaluate the Dare To Be Digital games purely on what is right there in front of them; just as they would be in their own home or local game store. And, as I discussed in my last blog they're only looking for one thing – fun. They don't care whether the teams almost killed themselves in the process or completed the project in their first week and spent the other nine weeks of the competition racking up impressive Donkey Kong scores.

The Way; The End: The Answer?

This is something Denki’s own Gary Penn recognised a long time ago as part of The Denki Difference. He maintains that there are two important yet distinct parts to the creative process which he refers to as “The Way” and “The End”. The End is the most important part, because it's the part everybody notices when they first come in to contact with a Denki Game. Very few, especially outside of our industry, have any appreciation for The Way, which is the process we use to get to The End.

Source: <a class=

That might sound complicated, but you’ll almost certainly be familiar with the underlying principle already. I always turn to The Beatles whenever I need to illustrate it: there have been more detailed books written about the songwriting and recording processes used by The Beatles than any other band in history. The reason is not that they did anything particularly pioneering that hadn’t already been tried elsewhere before, but because so many people loved the results - their songs. Their songs are “The End” and their songwriting and recording processes are “The Way”. If The End hadn't been so impressive far fewer people would ever have stopped to consider The Way. Yet, surprisingly, I still meet many game developers more obsessed with The Way than The End.

The same applies to Denki Games: if Quarrel doesn't make people smile when they play it then no one will care that we climbed a figurative mountain to create it. And that's what standing in front of your audience tells you without any sort of ambiguity – whether it makes them smile or not.

Much to our relief taking Quarrel busking proved to us that it connects with audiences just as we hoped it would. Passers-by were prepared to stop, have a go, and spend time chatting about it to learn more; all good signs that they’re engaging with the game.

We had almost 200 people play Quarrel over the three days. The majority of them played for over 30 minutes. Many of them came back more than once for another go, and many of them brought friends or family to play it with them when they did.

That's the best kind of feedback: it's all very well asking people “Do you like this game?”, but actions speak way louder than words as everyone knows. Someone going out of their way to come back with their wife and kids for a multiplayer game of Quarrel is worth ten filled in questionnaires saying “we think your game is great”. Although fortunately, for all you fact fans out there, we walked away with over 150 of those too!

Lessons Learned

Source: <a class=

Having found the process so successful in highlighting areas where Quarrel needs further refinement we fully intend to make “busking” Denki's games a staple part of our development process in future.

By considering ourselves entertainers rather than engineers or artists, it suggests other ways we can improve ourselves and our games too. Suddenly it becomes clear that creating an impressive piece of art or code is not enough in-and-of itself. Our work can't just be "good" when judged by the standards of ourselves or our peers; it has to be "good" when judged by the expectations of our audience, and they're rarely looking for the same things as friends or colleagues working in the industry. Our peers might appreciate technique, or flair, or some other subtle technical aspect of our work, but the chances are our audience isn't going to care - at least initially. "Having a laugh" is probably far more important to them than appreciating our subtle, technical mastery.

Of course, once they are having fun and being entertained then it's possible that they'll start to appreciate the subtleties that have been added by our considerable skills and effort as well. But going back to the busker example, unless we've earned our audience's attention in the first place, they're never going to appreciate how cleverly we chose to substitute that G7(9) chord for the BbMaj7 just before going in to the last chorus – the songwriter’s equivalent of using clever shading to hide a character’s low poly count. (Honest!)

Source: <a class=

What busking with Quarrel confirmed for me is that anyone working in an entertainment industry needs to consider their audience first - always. And what industry is more explicit in its role as an entertainment industry than "the games industry"? The clue's in the title, surely? If a Denki Game is engaging, exciting and rewarding for our audience, then we’re doing our job: we're entertaining people. If no one's stopping to play, then regardless of how well we might have performed our individual roles along the way, we've failed as entertainers in the end. Or someone’s playing the bagpipes close by – always a potential hazard in Edinburgh at this time of year! In summary then: focus on delivering The End. Document The Way. If your audience appreciates The End, your peers will appreciate The Way. ---Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like