Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Hinterland founder and creative director Raphael van Lierop reflects on The Long Dark's nearly decade-long journey--a journey that still has many miles ahead of it.

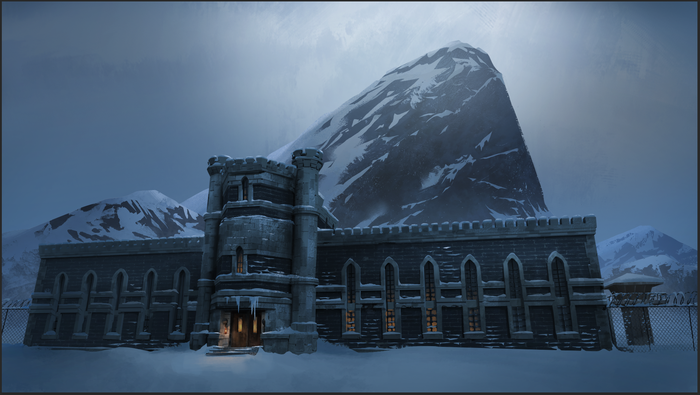

Last October The Long Dark hit a new mile marker on its long development journey that began almost a decade ago: Hinterland Studios released episode four of the game's story mode. The chapter, titled "Fury, Then Silence" partially shifts the game's setting from the open-world survival environment to the tight confines of a prison, putting the player in direct conflict with other apocalypse survivors in a space the game hasn't directly explored before.

When episode four released, Hinterland Games founder and creative director Raphael van Lierop called it a "bittersweet moment" because it was one step further toward the game's final concluding chapter. The Long Dark's development saga has now spanned three Presidential elections as well as a rise and fall of Kickstarter fads for video games, not to mention that its developers were doing remote work before remote work became necessary because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Now Hinterland Games has summited one of the final peaks on its own treacherous journey. It seemed like a good moment to take a metaphorical helicopter up this metaphorical mountain and see how the metaphorical climbers are doing. van Lierop was game to chat--both about making "Fury, Then Silence," and about the hybrid live game/premium game development cycle his company has found itself in.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Game Developer: Just to catch up, you’ve been working on The Long Dark in some form or another for a long time now. How’s it feel to be working on the same game for so long? How are you and the team handling the challenges of working with code and design from years and years ago?

van Lierop: One of the best things about how we designed and built The Long Dark years ago is that we had extensibility in mind. The game is extremely systems-driven and we’ve built it in front of a live community for so many years, so constant growth and evolution are core not only to the player experience, but to how we operate as a studio.

There’s always something to build on and improve, and we have new players joining us every day, along with players who have been with us for years, so things stay fresh that way. It creates a strong fundamental tension between the need to keep things appealing to the new, while also remaining true to the folks who have been with us since the beginning. It keeps things interesting.

Certainly we’ve started to hit some limitations with the tech and content architecture choices we made 7-8 years ago, so a lot of our focus right now is unwinding the game so that it’s easier to update moving forward.

To that end we recently shared the news that we are currently splitting the game between Story and Survival foundations to help make updating much more streamlined. We’re also thinking about how to take the game forward and make it feel more relevant to the “next gen” platforms like Xbox Series X and PlayStation 5.

This is the first game many of us have worked on that has transcended a hardware generation, so we’re learning a lot of lessons about how to build and maintain a game over several years, and those lessons are bearing fruit in this new world where making games evergreen is the holy grail.

But mostly, I just feel grateful to have a game that is beloved enough that people want more of it, a team that is happy to continue improving it, and a community that is happy to support us along the way.

The Long Dark has done a great job maintaining player interest in this survival game with a narrative component for all these years. What do you think you’re doing right in terms of getting fans to come back, or keep playing even as they wait a while for updates?

I think it’s all about update cadence, and delayed gratification.

If I can draw an analogy from linear entertainment, I think our episodes are a little more like big tentpole feature films, within our audience, in that they are these narratively dense experiences that we invest a lot of time and energy in to continue to improve our production values and the quality of our storytelling, while presenting this broader story about Mackenzie and Astrid and this idea of the Quiet Apocalypse and all the mysteries and drama around that. It’s a story about the people left behind. And people want to see how it all turns out.

Meanwhile, the gameplay and content foundation of the game is kept fresh and updated more frequently in Survival Mode. Those updates are more like episodes in a season of television, more about being engaged in the long-term arc of a thing. People see the evolution and they have a sense (or a hope) for how things will change over time, and they just want to follow along to see where things end up.

And then we hotfix in between, to fix bugs, optimize, improve quality-of-life for our players, etc. And by having these different content update cadences we are essentially creating different entry points for players to come back into the game depending on what type of player they are and what level of engagement they have with the game.

Some of our players are extremely hardcore and have thousands of hours of playtime, and they will dissect every changelist and create content analyzing our tuning changes and whatnot, so they will jump back in for a simple hotfix.

On the other end of the spectrum, some of our players are more likely to only jump in when we drop a story Episode, which means they may only check in every 18-24 months. And then the majority are in between and will jump in during a Survival update, or maybe they’re reminded by a seasonal sale, or their favorite streamer picks up the game, or when they see the first snowfall in their back yard, etc.

So within this community of millions of The Long Dark players, there’s always a good moment to jump back into the game, or the forums, and see what’s happening, see what has changed, and be a part of it. It comes from this sense of wanting to check in on an old familiar friend, to get some news, see how they are doing, and see what’s changed since you last checked in.

I was surprised to see this most recent chapter of The Long Dark's story mode (called Wintermute) features a prison setting, as opposed to the open wildlife area that defined the game for years. What made the team go for this more restrictive location, and what were the challenges in pivoting to a story in this space?

Each Wintermute episode has its own theme, and the characters and environment reflect that. After a lot of heavily open-world sections in the previous Episodes, which were very much player-paced, we wanted to lean into something that created a lot more tension as we head into the conclusion of the Wintermute storyline in episode five.

We wanted to put some constraints on Mackenzie, and force him to be face to face with some survivors who have a very different ideology, because so far he (Astrid less so) has mostly encountered like-minded folks who are just struggling to survive, like him.

Therefore most of the drama in episode four is focused on Blackrock Penitentiary, and this tension between a group of convicts that we first heard about back in episode one, who are completely self-centered and only focused on their own needs, and some other folks who are doing their best to help the people caught in between. Mackenzie is kind of tethered to all of it because Mathis has Astrid’s hardcase.

But he’s also fundamentally a good person, and given the choice between personal safety and taking a risk to help someone, he’s going to take the risk. And that puts him into conflict with Mathis and the others. So there’s a tension here, between the freedom offered by the world outside of Blackrock prison, and the hard limits Mackenzie finds himself navigating within the prison walls, and that tension is replicated both within the narrative and the player experience, to keep them aligned.

So, thematically episode four was about putting shackles on Mackenzie, and by extension, the player. In a lot of ways, open-world gameplay is the enemy of narrative tension so sometimes you have to take a bit of a heavier-handed approach to create that tension, that drama, and hopefully we found a good balance.

Otherwise you end up with too much of the “hey it’s the end of the world, now go pick flowers” situation you find in a lot of open-world games, which is great for player freedom but comes at the expense of creating that feeling of urgency, which is so critical for creating a sense of drama. We’re always trying new things.

Developers are usually under this tight pressure to release regular updates for any kind of “live” game to maintain player interest and keep numbers up—that’s generally for free-to-play games, but elements of that are creeping into premium titles as well. How has your team managed that pressure internally and externally?

Well, with free-to-play games you’re constantly watching your KPIs and tuning or tweaking your game in response to your player’s spending habits, and everything you do is highly optimized towards revenue generation. By contrast, everything we do is highly optimized towards quality and player satisfaction.

We sell the game, and we work to make sure our players feel their experience was worth the money they paid for it. Our key metrics for success are: is what we are producing high quality and good value for our players? Do we sell enough copies to keep the company going?

And most importantly, are we able to make things we are proud of and run a business in a fair and ethical way that lets us take care of our people. We aren’t trying to maintain a specific number of active players to hit some kind of financial metric. So our approach and the psychology driving our decision-making is completely different from some of those other business models.

I think the main pressure we feel is a sense of obligation to our players, wanting to live up to their expectations, and wanting to ensure they feel proud of the work we are doing and proud to be a part of our journey. And because we are focused on product quality, and we also feel a strong sense of responsibility for the quality of our craft -- the work we actually put into our games -- we are always willing to delay something if we aren’t happy with it, or we don’t feel our players will be happy with it.

And if we fail at that and ship something that didn’t meet expectations (because you don’t always know until something is out in the wild), we will also take the time and spend the money to go back and fix it.

All that said, we live in a new world that is increasingly dependent on subscription services, and the way we get paid by our platform partners is also changing, so in order to continue to succeed and be able to create new things in the future as an independent studio -- which is so critical for us, that independence -- we have to pay more attention to revenue generation.

Because the core business model of games-as-a-service is switching to be more like free-to-play -- you are exchanging easy access to a large number of players (for example, in a subscription) at a very low revenue-per-player number (say, a couple of dollars), for the need to find ways to sell them stuff later on -- we have to adapt our approach to business.

Our solution to this is very traditional, actually. We are considering shifting away from free updates to Survival Mode, to something more like a paid season pass, or paid DLC packs. Not nickel-and-diming our players, and only asking a very fair price.

This is something we’ve decided after a lot of years of giving content away for free, and it’s only because our players have basically asked us to create a paid path so they can give us more money.

But we know it’s a big change, and we know that a lot of players have been burned by other studios or publishers, so we’re approaching this very carefully. We don’t want to burn the good will we’ve earned over the years, because player loyalty to Hinterland and The Long Dark is one of the most valuable things we have.

Unrelated to this update but the last time we spoke, you were actually discussing how open-office workspaces aren’t great for all game developers, and that more would benefit from remote or hybrid setups. I guess the world gave you a chance to put that to the test! How’s the team been handling development during the pandemic?

Well, pre-COVID we had run the studio using a hybrid model for years. From maybe 2016-2020 we were all in the studio a couple of days per week and then worked from home the rest of the week. Very early on in the COVID outbreak, back in late February 2020, we actually shut our studio down completely and shifted to fully remote, just because it was the only way we could keep people safe. We’ve been working that way every since. So, basically two years now.

And it’s been fine! Not ideal, probably not what we would prefer, but it’s been ok. Our focus has been on keeping people and their families safe and healthy.

Our productivity and output as a team has certainly suffered, but it’s a fair trade. I honestly can’t understand other developers that have forced their teams to come back to the office, or some who never really closed their studios at all. It’s mind-boggling to me.

I think the most useful take-away out of the COVID experience is the recognition that different people need different things to feel empowered, healthy, and productive, and these things change often over the course of a single day! So this idea that we should all get together in physical studios for 8 to 10 hours a day -- in open or semi-open offices -- and then expect that this “one size fits all” approach would work, has been massively debunked. It’s clearly just not true or viable.

At Hinterland, we’ve always valued autonomy balanced with accountability, and COVID has just allowed us to lean into our strengths in those areas. Early on, before COVID, we realized that flexibility and trust is what people valued most about working at Hinterland, so we built our approach around that, and a global pandemic just reinforced what we already believed.

But we also understand how important it is to give people the opportunity to bond and create trust between each other, and that requires spending time together in-person to create memories and strengthen personal relationships. It’s just not really possible to do that over a zoom call. That’s not how our brains work.

In the past, we got little bits of this bonding “for free” just by being in the studio together, and now we have to be more deliberate about it. Our solution is to be remote-first, maintain a physical office for those who want to use it, and then supplement with quarterly offsite retreats focused on socializing and making memories together. That’s the Hinterland recipe.

We’re hoping that after being fully remote for two years, that 2022 will be the year we’re able to put these beliefs back into practice again. Fingers crossed.

But no matter what happens, we’ll continue to focus on safety first, and then our high-autonomy/high-accountability culture, because that has made us who we are as a studio. And COVID has only reinforced the strength, and importance, of that approach.

You May Also Like