Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Because we had a lot of fun designing the AI for our turn-based strategy game, Powargrid, as well as building AIs for other games like OpenTTD, we added a Lua scripting interface to the game to let players program their own AI.

We recently added a feature to our turn-based strategy game, Powargrid, we are very excited about: a framework that allows you to program your own AI to pit against yourself, your friends, and other AIs.

In a typical game of Powargrid, the goal is to destroy your opponent's power plants while protecting your own by building power lines, substations, towers and cannons to attack and defend. The rules are simple, but (we think) they result in a complex strategic game.

We had a lot of fun designing the AI for our game, and spent a lot of time just watching computer players have a go at each other. It's fun making the AI as mean as possible, but in the end the primary design goal was to make it fun to play against. We have a bit of a history making mean AIs, though: with two other friends, we once won a contest building an AI for OpenTTD, the transport simulation game, by exploiting the hard work of other AIs by using their roads and some creative use of game mechanics (you don't need to send trucks back and forth - you can just sell them at the destination and buy new ones at the pickup point!) Ah, good times...

So - one thing we knew we really wanted for our game was a way for players to write their own AIs. We chose Lua for our scripting language, due to its popularity for scripting and modding games. Famous examples include Civilization and World of Warcraft. Our game is made with Unity, and the MoonSharp Lua interpreter is very easy to embed.

Writing an AI isn't easy, so I made sure to include to include some debugging tools, an example AI, and a set of library modules that define useful abstractions on top of the low level API the game provides.

It's the most basic method of debugging, but it's never let me down: print stuff to the screen. Your AI can write messages to the AI debug console, which is visible if you've checked the "Enable dev tools" box in the Add-ons menu. Simple "print" statements will go there. If you want to get fancy, you can use the Debug.info, Debug.warning and Debug.error functions to write text in different colors according to how urgent a message is.

Another important feature is the reload button: you can edit and reload your AI scripts whenever you want, and the changes will take effect on the next turn. Quick iteration makes programming a lot more pleasant.

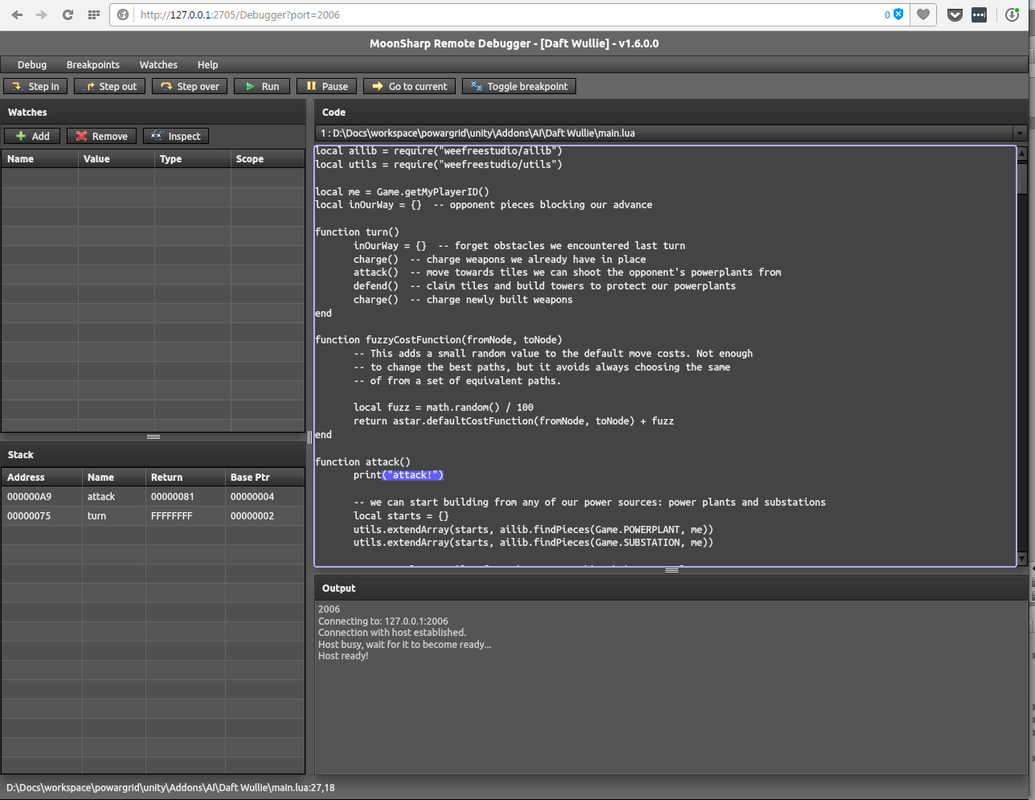

As mentioned, we use the MoonSharp Lua interpreter to run user AI scripts. It comes with a pretty decent debugger, which runs in your browser. The in-game console has an "Open debugger" button that starts the debugger and opens a browser window. The debugger will pause your script at the start of the turn() function, and you can step through the code, set breakpoints and watch variables.

I considered it essential to ship an example AI with the framework, for two reasons: a good example is a much better way to get to know an API than any reference documentation can provide, and of course I had to test the API I was designing to make sure it actually worked.

I called the example AI "Daft Wullie", after a Discworld character, because both Willem and I are huge Terry Pratchett fans :)

Basically, Daft Wullie contains a simplified version of the logic of the existing "built-in" AI (created long before we added the scripting framework). Each turn, it goes through 4 stages:

charge: evaluate if any existing weapons need to be charged (charging a weapon means it'll fire after your turn)

attack: use pathfinding to figure out the best way to get to a spot from which it can hit the enemies power plants, destroying obstacles along the way if needed

defend: see which tiles its own power plants can be shot from that the opponent is able to reach next turn, and try to claim those tiles; build weapons to counterattack opponent weapons already in place

charge again: see which newly built defensive or offensive weapons should be charged

Describing the workings of the example AI is an ongoing process over in this forum thread.

The API or Application Programming Interface defines the interface available to a programmer to interact with another system - in this case, our game! The API defines the functions your code can call do to get information about the current game, and to perform game actions like building things and charging weapons.

Your AI script has access to two global objects with useful functions: Game and Debug. Debug just lets you write stuff to the console. The Game object is what lets you see and manipulate the game grid. It has functions to look at the current game state, like GetMyPower(), GetPiece(x, y), GetHitPoints(x, y), and functions to take actions: Build(piece, x, y, direction) and Charge(x, y).

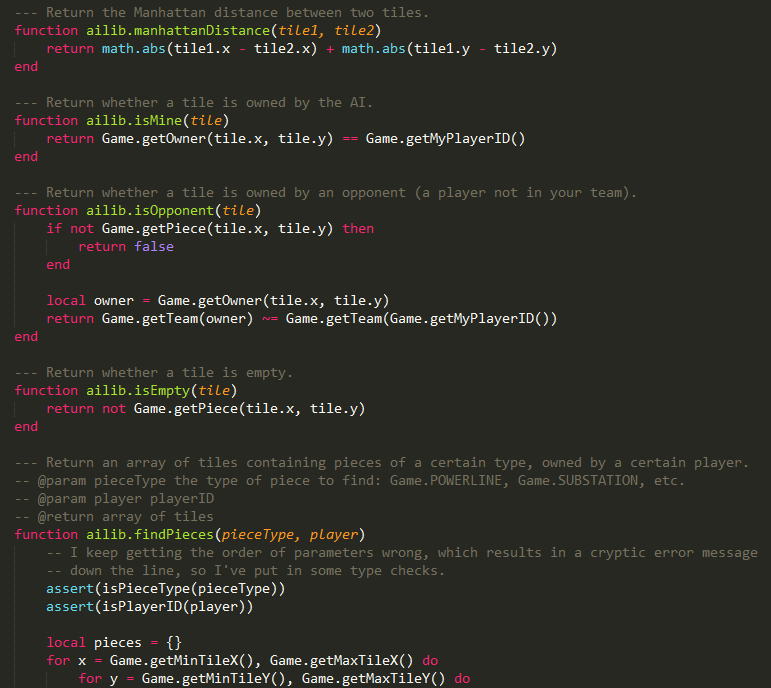

Of course, those are very low level functions, and to make your life easier, I added a few modules with useful functions, including an A* pathfinding implementation for navigating the grid. These are written in Lua, so you can look at the source code and copy/modify/reuse whatever you like! In ailib.lua, you'll find higher level function like ailib.findPieces(pieceType, player), ailib.canHitFrom(tile, withTower, withCannon, cannonDirection) and ailib.getBuildCost(pieceType, tile). LuaDoc makes it easy to generate nice documentation for these modules.

There are many ways to figure out where to go on the grid and how to get there, but you'll probably want some sort of pathfinding algorithm, and A* is great! It's my favourite algorithm. My wife thinks it's strange that I even HAVE a favourite algorithm, but hey, that's what she gets for marrying a nerd :) It's easy to tweak the AI's strategy by adjusting the cost function.

I've writting more about pathfinding in general and how we used it to create the built-in skirmish AI in this blog post: http://www.powargrid.com/blog/powargrid-ai-part-1-intro-and-pathfinding.

After discussing the user facing side of the framework, I figured I'd also "pop the hood" as it were, and look at some of the implementation details for the scripting framework.

Playing against someone else's AI means running their code on your computer. We have to ensure that it's safe to do so: we don't want an AI to give someone else access to your computer, to delete your files, or in fact even look at them. That's why the AI scripts run in a secure environment, called a sandbox.

The sandbox strictly limits the files an AI script can access: you can use the "require" function to load additional modules, but you can only load Lua files, and only from two places: the AI's own directory, and the Shared directory that contains utility modules you may want to share between different AIs, like our ailib module.

We also limit the built-in Lua modules you can use. For example, you can have math, string and table, but not os, the interface to the operating system. MoonSharp also requires you to register all classes you want scripts to be able to interact with, so scripts can't get a hold of the .NET or Unity classes to break out of the sandbox. The only .NET types the script sees are the Game and Debug classes providing the API.

API calls should be blocking: if you say "build me a power line", that power line should be built when the function returns. This makes for a much nicer interface than, for example, something based on callbacks.

an AI script must not be allowed to freeze the game while running, even if it goes into an infinite loop.

AI scripts must not be allowed to interfere with each other.

To make that happen, each AI script gets its own Lua interpreter and runs in a separate thread.

Multithreading is hard, especially when you're trying to share data between threads - so we don't, or at least, we share the absolute minimum.

When it's the AI's turn, the framework takes a snapshot of the current game state: how much power does each player have, what buildings are on the board, how many charges does each weapon have, etc.

If the AI calls a function that just returns information about the game state, this is answered based on the snapshot. Since Powargrid is a turn based game, nothing can change until the current player makes a move.

When an AI calls a function to change the game — for example, placing a building — the AI thread enqueues this command and on the next frame, the AI framework, running on the main thread, picks up the command, tries to execute the action, puts the result (whether it was built or not) on the response queue, and takes a new snapshot. The AI thread that was blocking on the response queue picks up the response and returns that to the Lua script as the result of the "build" command, and the AI can continue.

That's it, in a nutshell! If you're interested, drop by on our AI forum or Steam community hub, take a look at the API docs and the example AI, get yourself a copy of Powargrid, and start hacking!

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like