Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this postmortem from the final (June/July 2013) issue of <a href="http://gdmag.com">GD Mag</a>, Brandon Sheffield turns the critical lens inward to examine the ups and downs of GD Mag's 19-year legacy.

In this postmortem from the final (June/July 2013) issue of the magazine, former Game Developer magazine editor-in-chief Brandon Sheffield turns the critical lens inward to examine the ups and downs of the magazine's 19-year legacy.

Game Developer has had a good run. We started in March 1994 as a quarterly, and moved quickly into a monthly publication as demand grew. Over the years we've seen over two dozen editors, multiple company name changes, four major design overhauls (frankly, there should've been more), and hundreds of articles that have helped developers do their jobs better (we hope).

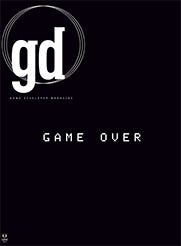

And now, a few months shy of its 20th birthday, after winning a slew of magazine industry awards, Game Developer is coming to a close, because print is no longer an attractive market.

There was a lot more we wanted to do, and we hoped to be able to serve you for years to come. The magazine was taking more of an indie and small-team bent under Patrick Miller's leadership as the market has shifted in that direction, and we hoped to open a venue for a host of new voices.

As the magazine's longest- running editor, at eight years, I thought it might be fi tting to do a postmortem of the entire operation in this, its fi nal issue. Plus, Patrick and I fi gured that since we had been asking devs to take a frank look at what went right and wrong with their work for so long, it was only fair that we do the same with ours.

People respected the magazine, which certainly made us editors happy. Often at trade shows we would get comments like "Oh, Game Developer! That's the one publication I read!" Granted, most of these people were getting the magazine for free, but it was clear that people viewed it as respectable (even though most folks outside the U.S. had never heard of it).

No offense is meant to our Gamasutra siblings, but we would often get pitches saying, "Well, I guess I could put this on Gamasutra, but I'd really like to have it in print." For some people, print still had that allure of being "published," and having written something of import. It's almost analogous to the prestige of making a console game -- we grew up with it, so it must be "better," right? This is why so many game developers have blindly put their games on consoles, when other platforms are doing much better. We like history, I suppose!

No offense is meant to our Gamasutra siblings, but we would often get pitches saying, "Well, I guess I could put this on Gamasutra, but I'd really like to have it in print." For some people, print still had that allure of being "published," and having written something of import. It's almost analogous to the prestige of making a console game -- we grew up with it, so it must be "better," right? This is why so many game developers have blindly put their games on consoles, when other platforms are doing much better. We like history, I suppose!

That went for us editors, too. Every month we would pour ourselves into this thing, staying up late, working overtime, putting final touches and making last-minute edits to ensure the magazine was the best it could be—and at the end of our monthly cycle, we'd have an actual product we could touch. It's a great feeling. Many game developers work for years on a game, and when it's out, they have to start all over again. We got to do this monthly, knowing we were actually creating something.

As much as I personally wanted to differentiate the magazine from its parent company, I will admit that our ties with GDC were helpful. We got greater visibility at the shows, not to mention a generous ad boost, and it didn't hurt that the higher-ups looked at the magazine as a sort of soft marketing arm for the show. It helped us maintain relevance and ground to stand on as other magazines closed around us. That couldn't last forever, but it helped for a time.

In fact, I think a greater convergence would've been helpful -- turn Gamasutra into gamedeveloper.com, and unite all the properties. But, alas, we will never know!

For over a dozen years the magazine had been running reports like the Salary Survey and the Front Line Awards, which are the only contiguous running reports on game developer salaries and ranking of game development software—period.

Neither of these was perfect, we'll be the first to admit, but there wasn't much better to be done. As my former managing editor Jill Duffy said to me, "We did that shit right by hiring an outside expert to conduct the survey and analyze the results, and it was smart to stick with the same contracted partner year over year."

Since statistics were outside our wheelhouse, for the Salary Survey we used a professional (and expensive!) statistician to sift through thousands of survey responses to bring us valuable data. Some folks have criticized the survey, because they feel the numbers are inflated -- but it's really the best we could have done without somehow getting all dev studios to give us their employee numbers. When that's the sort of industry we work in, we'll all be holding hands and hugging rainbows, and won't need money anyway!

The Front Line Awards are some of the biggest industry awards on the game development software side, and companies actually cared about these things. Epic, for example, has been touting its running tally as best engine for a number of years.

We've had a few other surveys and objective reports throughout the years, and have always done our utmost to make sure they were accurate. A lot goes on behind the scenes with these things, and I think we did quite well with them.

This is tooting our own horn a bit, sure, and we've edited a whole lot of horn-tooting out of postmortems in the past—but it's our last issue, so begrudge us this. Our editors were pretty hardcore. We stuck to a style guide, did multiple edits and multiple art passes of every article, and generally tried to make the best magazine possible. One doesn't think a lot about the layout of printed words on a page and how they're juxtaposed to images until one has to lay out a feature with more than 30 figures and code listings.

The magazine is currently done in large part by two people: editor Patrick Miller and production manager Dan Mallory. We have a part-time art director in Joe Mitch, a part-time sales lead in Jennifer Sulik, and up until very recently, we had Pete Scibilia in New York to interface with the printers.

That's it. We have contributors, sure, but it's a really lean operation. Only two people are working on the magazine full-time, and that's how it's been since around 2005. I sometimes think it's a miracle that a 52- to 96-page issue of any quality gets pumped out every month, but there it is.

We've had many editors over the years, but most of them didn't work together. Through hard work and a dedication to the craft, we managed to create a magazine that people liked, with what amounts to a skeleton crew.

Many, many folks out there were more than happy to write a postmortem for the magazine ("That means we're on the cover, right?") -- until it came to the What Went Wrong portion. But we took it as a point of pride that we were able to offer developers a chance to be frank and honest about their work and the industry, even if it meant that every so often we'd fi nd out that we couldn't publish a postmortem we had spent weeks editing and revising with the writer because "crucial stakeholders still needed buy-in."

The game industry has precious few places where developers are encouraged to be honest with each other, and Game Developer was one of them. We truly believe that this is one of the best ways to help fellow devs make better games and advance the medium overall, and we wish Gamasutra the best of luck in carrying this tradition in the future.

To be sure, it's one thing to expect our contributors to write frankly about their professional shortcomings, and another to do it yourself. We fully acknowledge that Game Developer stood as strong as it did due only to the brave devs who were willing to bare their souls in print for the sake of helping others learn from their mistakes. After all, we couldn't have done anything without the hard work of 19 years of contributors and columnists, so ultimately, anything we've accomplished over the magazine's run is your accomplishment as well. Thanks, everyone.

Game Developer magazine was (mostly) free to qualifying customers, and like most business-to-business magazines, we relied on advertisers for revenue. Because of this, industry contraction hit us hard, throughout my tenure at the magazine.

First, we saw consolidation in the game software space. There used to be a whole slew of tools that advertised with us -- then, one by one, they started to get swallowed up by one company or another. This turned a hydra of advertisers into just a few sales points. They could advertise one product or another in a different issue, but since they were no longer competing, they didn't advertise in the same issue. This drastically reduced the number of advertisers in our pages.

Next to go was recruitment. Advertisers found it more valuable to advertise in Gamasutra, which had a wider reach and could be shared via the internet. They have moved even further into direct recruitment through Twitter and the like.

Couple this with the fact that from at least 2004 through much of 2011, we had nobody specifically assigned to do sales for the magazine. The emphasis was on GDC, which is obviously much bigger than the mag, and package deals. At one point some sales staff were making package deals with GDC and Gamasutra, getting multiple pages in the magazine as part of the deal. Digging hard through the corporate structure, I found that in one instance we actually sold magazine ads for less than it cost to print the pages they were on. Suffice it to say, that never happened again, but these deals weren't exactly giving us blockbuster profits.

Just as I was leaving, we got Jennifer Sulik in sales, who did a great job of bringing in new advertisers (from smartphone makers to auto companies), and getting our numbers stable. In fact, the magazine was on target to meet its profi t estimations for this year. If we had gotten a dedicated salesperson earlier in our life cycle, I can't help but wonder where we'd be now.

This may surprise people to hear about a magazine that's closing down, but Game Developer was always profitable. Maybe not every month, but it was profi table every year of operation (so far as I know). To be certain, our contribution to our parent company (that is to say, our profit) was declining, but it was still profit! We kept lean, kept regular advertisers, and managed to squeak through a bit of digital revenue. You couldn't really do much better as a small-circulation magazine, but it wasn't good enough to keep our parent company's skin in the game.

We rolled out our digital edition last year, and it was quite successful. But we should've done it years ago. Frankly, our infrastructure was so scattered, and our crew so small, that nobody had time to make it happen. We were too busy trying to get through the next day.

We rolled out our digital edition last year, and it was quite successful. But we should've done it years ago. Frankly, our infrastructure was so scattered, and our crew so small, that nobody had time to make it happen. We were too busy trying to get through the next day.

Many magazines were switching to a more digital-oriented model and trying to get actual paying subscribers, but we began the transition too late, and our digital model was imperfect at best. Many subscribers mentioned that they had a better experience by downloading PDFs of the magazines and reading it in a PDF viewer than they did with our actual app.

As has been hinted a few times in this postmortem, we were a bit starved for support. The magazine was chugging along at an even pace, which was great in some ways, because we didn't get a lot of scrutiny from the higher-ups. They were content to just let us do our thing. But at the same time, we also didn't have much support when we wanted to do something new -- like launch a mobile edition, get new advertisers, reach new markets, and so on.

In early 2012, we finally got someone on staff -- Pearl Verzosa -- to tackle this sort of thing, but at this point in the magazine's life cycle, it was viewed as extra overhead, rather than an overhaul of a valuable piece of the business.

I mentioned that we had to share sales staff for many years, but sharing art staff was difficult as well. I went through a few art directors in my time, and Joe Mitch has been a great one -- but he was often pressed for time, and had to squeeze the entire look and feel of the magazine into four or five days' work. In fact, that's all he was budgeted for. This could lead to bottlenecks that would have a ripple effect through production.

But through hiring a professional production editor (instead of simply training one, as we'd done for years), and having a decent support team, the operation was finally running smoothly -- just as it all came to a close.

I joined the magazine in September 2004. Just a scant few months before that, there had been an editor-in-chief, a managing editor, a features editor, and an assistant editor. There was an on-site group of people to support magazine production, an in- house sales staff, and much more.

In the interest of retaining profitability for the magazine, the parent company took these positions and cut them or merged them into other departments. Most of the additional work got pushed on the editors. We became responsible for final magazine production, which there had previously been an entire department of five people for. We became the direct line to sales, instead of having an ad production person in between. We started doing our own layout.

Whereas before, we were just taking care of the words and occasionally helping with image sourcing, we were now in charge of almost every aspect of production. The increasing workload made us editors increasingly frazzled, and it became harder and harder to see the long view with the magazine.

We were scrambling to get a single issue out. What's more, we couldn't afford to hire professionals much of the time, so we would hire amateurs or neophytes and train them. This put a lot of strain on the senior staff (read: me) as we got everyone up to speed.

When you consider the fact that none of our authors were professional writers (they're all game developers, many of whom don't claim English as a first language), a lot of these articles needed a lot of massaging, multiple rewrites, and hardcore copyedits. This became harder and harder to get right as we had to do more and more things that weren't editing.

Streamlining our production process eventually got this to a stable state, but it was never an easy job. In the end, we were able to make a good magazine with a skeleton crew, but just making a good magazine wasn't enough to keep up with the times.

Who will mourn our passing? This is a strong admission here, but we never really, truly knew who our audience was. As a print publication, all we had to go on were the few emails we got, and our interactions with developers at trade shows. We never knew for sure if we were serving our audience, because our audience kept changing.

Our surveys showed our audience included a lot of programmers, so we tried to accommodate them -- but we also wanted to serve every aspect of the community. Case in point: Only two percent of surveyed readers called themselves audio professionals. And yet we maintained an audio column until the very end, because we believe audio is an absolutely vital part of game development.

We got a lot of flak from programmers for not having articles that were innovative enough. But we'd ask them what sorts of things they'd like to see, and they'd grow silent. "How about you write something you'd like to see," we'd ask -- but nobody was falling over themselves to offer solutions, only criticisms.

We got a lot of flak from programmers for not having articles that were innovative enough. But we'd ask them what sorts of things they'd like to see, and they'd grow silent. "How about you write something you'd like to see," we'd ask -- but nobody was falling over themselves to offer solutions, only criticisms.

We had to try to predict what might be important, asking our advisers and peers for input. We certainly weren't perfect, and I'll be the first to admit there were some issues that were basically duds. But we had no real hard data to go on; your average Gamasutra article got more feedback than we would on an entire issue.

A number of people who said to me they would miss the magazine when they found out about its closure also admitted they got it for free and threw it away every month. Who was our audience, really? Will they miss us? Will you?

I will miss the magazine. All of us editors (and former editors) will. We did our best to try to help the industry we love, by providing a resource, and a venue for the various voices of our craft. We wanted to help you make better games, and I can only hope we had some small impact in our two decades of work. I honestly thought we might be the last game magazine left alive after all the others fell, because we were profi table, and couldn't slim down any further. But a small profit sometimes just isn't worth the time spent working on GDC and the company's other endeavors.

Thanks to all the editors, all the contributors, all the copyeditors, all the advisers, and all those who ever wrote to us, or spoke to us about the things we were doing. For me, at least, that was what kept me doing this. The fact that I knew someone out there, somewhere, was reading. Maybe, just maybe, they took something away from our words.

[You can get the entire final issue of Game Developer magazine as a .PDF here - and watch for a full archive available on GDC Vault in the near future.]

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like