Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The makers of the indie rhythm action game Aaero initially resisted making a necessary change to how shooting worked in their game because they didn't want to be accused of being "too 'Rez-like.'"

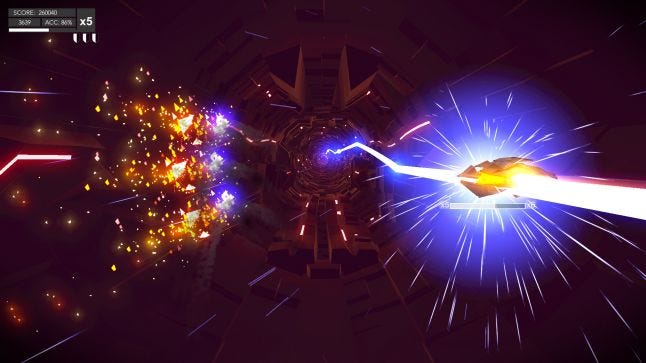

Aaero, a shooter that flows in time with a music track, manages to carve out its own unique feel, distinctive from recent rhythm games like Thumper. It was developed bu Mad Fellows, and the team is open about its sources of inspiration, which aren't necessarily what you might think.

At first glance, Aaero seems to have drawn upon the 2001 music rail shooter Rez. While Tetsuya Mizuguchi's masterpiece of flight, sound, and visuals was not unknown to the developers of Aaero, they were far more influenced by an element found in in iNiS's 2001 rhythm title Gitaroo Man.

“We didn’t have Rez in mind when we started developing Aaero.” says Paul Norris, creative director at Mad Fellows. “A ribbon-following mechanic was our starting point, and this is most influenced by Gitaroo Man.”

Norris had set out to tie music, visuals, and gameplay from the very beginning, having players flow along a ribbon as they shot down enemy fighters and ships. It was meant to contain a sense of touch – of contact with the game’s world through actions and movement - and also contain a dizzying sense of moving along with the music.

However, while seeking that perfect balance of shooting and music – in demanding more of the player than just firing along to the beat – Norris eventually found himself drawn to some of the design decisions that had been made by the makers of Rez.

Norris told Gamasutra about the lessons that the Mad Fellows team took from other games, and what the process of making Aaero taught them about the design decisions behind other classic rhythm titles.

"Aaero’s originality comes from the ribbon tracing gameplay," says Norris. "We knew exactly how we wanted this to be. It needed to be tactile and satisfying. We talked about angle grinders and arc welding when discussing how it should feel.�”

Mad Fellows looked at how to make every player action a part of the song - gameplay and visuals are shaped as beats. “Instead of working in seconds and milliseconds, we set everything to a musical time," says Norris. "Aaero ‘thinks’ in beats and bars. For example, an animation may be set to loop over one bar, meaning that the same enemy asset will move in time with the music regardless of which song it appears in.”

Through this, Norris could make actions flow along with the music regardless of which song they’d chosen. Every aspect of the game would be designed to follow beats, shaping itself around the track and mirroring the natural rhythm the game sought to create.

This is only part of how Norris thought of each aspect musically. “All of the gameplay design is done in a music sequencer," he says. "The ribbons, enemies, obstacles, tunnel sections and models are all designated a MIDI note. I then produce a MIDI track that is fed into Dan’s tools to create the tracks. Once this is done, we do an ‘art pass’ to place extra key features, polish the visual composition and add the effects and lighting.”

Each element was shaped as a piece of actual music, and these pieces are put together with the game’s licensed tracks to create a full song of moving, interactive gameplay elements. In this way, while creating a level, the developer is also creating a song.

There was one issue, though. Norris had done all that he could to shape the game through music, controlling it so that the player would be immersed in an experience where they were an inhabitant of the music through their every action. The player, however, can shoot when they like, something that had the potential to throw every other aspect of the experience out of whack.

While everything else in the game was being carefully tracked and accounted for, the player could fire off the beat, forcing the devs to somehow accommodate a player’s unique, potentially erratic firing style in the music.

They tried a handful of different ideas to see if they could work through it. “We had core gameplay feelling functional. The ribbon following gameplay was in place, and we had a sort of Elite Beat Agents/Parappa mechanic for shooting.” says Norris.

This style didn’t quite feel right for Norris, though. It kept leading into that sort of timed tapping that he didn’t want the game to play like. Having players shoot freely would bring about a separation between player and game world, with their actions no longer mirroring what was going on in the game. The first solutions that presented themselves just involved tapping along with the beat, but that was still having the player control the rhythm, not become a part of it.

“We wanted to avoid rigidly tapping in time to the music. That had already been done, and it felt as if Guitar Hero and Rock Band had taken this as far as it could go,” says Norris.

Tapping to the beat can make the player feel more like they were playing the music, but this gives more of a sense of being a part of its creation. The music is something you create with your actions, creating the song by moving in time to it. Norris wanted players to feel that music, and as such, their actions had to almost feel predetermined by the song. No matter what the player did, it had to fall in time with the music to make them feel like a piece of it – the music is what’s in charge.

Their musical choice wasn’t making things easy, either. “We have a licensed soundtrack, which is usually reserved for games that stick to ‘tap in time’ style gameplay due to difficulty in creating compelling freeform gameplay closely tied to a pre-set piece of music.” says Norris.

The solution was one that Norris had stumbled across years before. “I had a PS1 demo disk of the first area of Rez. It made a big impression on me," he says. "It was an experience more than a game. I eventually got the full game when Rez HD was released on X360.”

“I think Rez was ahead of its time in many ways," he adds. "It was an ‘art game’ before they were even a thing.”

Rez held the final key that Norris had been looking for, and had enjoyed years previous. Like in Rez, the shots in Aaero could be fired as the player liked, but it was the timing of the impacts that would be controlled along with the beat. By having players launch a salvo, but the game guide it, players would still retain control over play, but Norris could keep things on beat without forcing players to tap along with a beat to fire their shots.

Despite this being a solid solution, that doesn’t mean Norris was quick to adopt it. “Until this point, Aaero had been one of those projects that had just fallen together," he says. "It had been fun and compelling to play since the original prototype. Now, I found myself agonizing over it becoming too ‘Rez-like’. It was naturally leaning towards emulating the shooting in Rez. I had to decide if I let it continue that way or intentionally dragged it away for the sake of originality. Was ‘too Rez-like’ even a bad thing?”

Eventually, Mad Fellows decided to adopt the established shooting mechanic. "Things will always explode on beat, but you can still fire your missiles whenever you decide to," says Norris. "The game adjusts the missile trajectory to compensate.”

For Norris, the decision may have been difficult, but it was what seemed best for the game itself. “In the end, I decided that intentionally designing away because it overlapped concepts covered in another title was unlikely to produce the best game," he says.

Norris points out that other more established genres don't spend as mucb time fretting about how certain features of their game resemble what's come before. "If studios had that attitude when developing FPS titles, they wouldn’t have progressed as much as they have," he says.

You May Also Like