Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Happy 30th birthday to The Legend of Zelda! We talked to several designers about how the epochal adventure changed the perception of what a console game could do--and how it personally inspired them.

The Legend of Zelda was released thirty years ago in Japan, on February 21st, 1986. It wasn't released in the United States until August of the following year, but we're celebrating its birthday now.

Zelda shifted the tectonic plates underneath the game industry; three decades on, we still feel reverberations from Nintendo’s original role-playing adventure.

Why has this game, one of countless riffs on age-old fantasy tropes, lived on while others drifted away? What made Hyrule and its savior special?

We consulted with several game designers for their take on how the epochal adventure changed the perception of what a console game could do--and how it personally inspired them. Here are five features that made the original Zelda more than just another romp through the woods.

(via titlescream.com)

Koji Kondo’s music starts immediately, and we see the game's title. It's not just text on a black background that players were accustomed to--it's written in thick script with shadowed edges, surrounded by green vines. A long saber underlines the title. Rocky outcroppings frame the periphery of the screen. A golden inverted triangle flashes in the background, and a waterfall cascades below.

Cue fade-out to a scroll of text laying out the back story, followed by a list of every item in the game. Kondo’s theme plays in half-time, not giving away the jubilant theme that will soon score your heroics but hinting at a yet-unknown grandeur. Wait long enough and a pixelated Link will appear, holding up a sign with burnt edges that advises you to “Please look up the manual for details.”

This was no usual title sequence. One part animated sprite painting, one part ingredient list of the raw components of the adventure to follow. It’s a shame that most players likely pushed “START” before taking in the whole luscious thing.

The game's opening has its supporters and detractors; sometimes, they're the same person. “The first scene in the original The Legend of Zelda is one of the best moments in videogames,” writes Ian Bogost in his October 2014 EDGE column. But for him, the spell is broken with the transition away from the flashing Triforce and the gleaming waterfall. “Seconds later,” he writes, “everything’s ruined.”

For some, the trite and poorly translated story--"MANY YEARS AGO PRINCE DARKNESS 'GANNON' STOLE ONE OF THE TRIFORCE WITH POWER."--saps any sense of wonder evoked just moments before. (There's a better translation in the Gamecube version.) And graphically, nothing in the game proper matches that first ambiguous glimpse into a strange, dangerous place. By the time Link slashes his sword, Bogost laments, “The Legend of Zelda is pure mechanics: go find the treasure and save the princess.”

But I disagree that the text-scroll and item list drains away any majesty found therein. It achieves something even greater in its transparency. This is why we are here, the game seems to say. Here is all that you will find and use.

That the adventure remains so thrilling, no less today than in 1986, is a testament to those very mechanics and the purposeful world you are tasked to discover. The opening baldly states: This is a videogame, not a film or a novel. The point is in the playing.

Most early console games aped the confines of arcade hits, like the neon labyrinth of Pac-Man’s single screen or Centipede’s pachinko-like vertical extermination simulator. Nintendo’s Super Mario Bros. painted the sky blue and gave us eight worlds to explore, blowing open expectations of what a game could contain. But you largely moved in one direction.

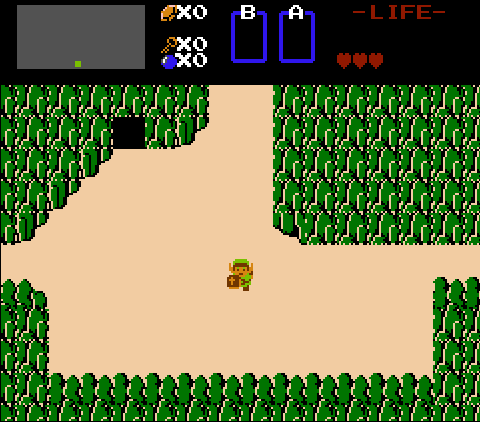

The Legend of Zelda’s single largest achievement is its faith in the player. You are not confined. You are given free rein to go where you please. The first screen you see is an overhead view of your character in a field surrounded by mountains. Paths await to the north, to the west, and to the east. A single black opening in the rocks beckons.

You can take any of these four directions to begin the game. You are not shunted down one or the other. That freedom continues throughout the game, and with it, the notion of an “open world” game was largely invented.

It broadened the paradigm, expanded player agency, and it continues to inspire developers. Daniel Remar of Ludosity explains how their sequel to Ittle Dew draws on this idea. “The philosophy behind Ittle Dew 2 was to make a game more in the spirit of the original Zelda, with its focus on player freedom and secrets,” he says. “We wanted to uphold the spirit of that game, where everything was more immediate and the game trusted the player to figure things out for themselves.”

In recent years, the ‘open-world’ genre as executed in large-scale console development has metastasized, evolving into grandiose landscapes filled with bobbles and tidbits to collect or roaming creatures to eliminate. It can feel liberating, but it can also feel like your quest’s purpose has been boiled down from exploration into something closer to the mandated litter collection of a prisoner on the side of the highway.

A few blockbuster experiences maintain Zelda's feeling of wonder. From Software’s Demon Souls and Dark Souls games are often cited as the most direct descendant of that original Zelda world, offering unabated freedom... and punishment to those unwilling to learn or be patient.

Most early game worlds had a hard enough time establishing their environment through the limited graphics technology of the era. Players came to simply accept that a patch of green was probably supposed to be a bush as they navigated past it. Zelda turned exploration into more than finding the end of a labyrinthine maze. Use your torch on the right foliage and the leaves burn away, revealing a door hidden in plain sight.

The map was an unreliable narrator.

Sean Velasco, designer at Yacht Club Games and director of Shovel Knight, remembers how different this made the world seem from its contemporaries. “I think what impacted me most with the original Zelda was its item-based progression, and how the items fit into the world's structure,” he says. “It made me see the world as a puzzle just waiting to be solved. Instead of boring locks and keys, it was organic! Every cracked wall, single-tile gap across water, or conspicuously-placed bush seemed bursting with possibilities.”

Each item obtained has a primary action (the bow shoots arrows) but can function in multiple ways (that arrow can now shoot a far-off switch). Once you understand how each works, the world around you looks different. What at first seemed impossible, now with the right tool in hand, could be returned to and conquered. Velasco still holds up Zelda as the “perfect marriage of theming, environment design, and gameplay.”

With its secret tunnels and unexpected consequences, Nintendo allows for its game’s floorplan to be broken in surprising ways. Maybe this is why the player is shown every single item to find in the game during that opening title sequence. The same introduction would be blasphemy in today’s spoiler-sensitive climate. But the designers knew they weren’t really giving anything away. A tiny flickering flame animation only tells us that this is fire. We still need to find what burns.

(via CIBcollector)

It’s August 1987 in North America. An early-adopter of the Nintendo Entertainment System will have had over a year of plugging boringly grey molded plastic into the VCR-like slot of their console. But this one is different. You notice something before even opening the box; the box cover’s three emblems--a key for Wisdom, a lion for Courage, and the self-explanatory Heart--adjoin a gold rectangle, slightly ribbed. Only if you look closely do you see that the rectangle is actually a window, the box cut open to reveal the cartridge within.

And it’s gold. The cartridge is gold.

Many kids can't help but think, if only for a second, “That’s real gold.” And even knowing that you're looking at a standard cartridge coated in a special paint does little to dim the aura of special worth.

The message of the special package is clear: Something valuable has been unearthed. This game is literally a piece of treasure.

The original Japanese version, released for the Famicom Disk System, was yellow (most FDS games came in different colors). Nintendo of America decided to bring Zelda over coated in a reflective golden sheen, and this set into action a tradition that continues, if sporadically, with sequels and Zelda-themed merchandise. Unboxing videos of these gilded games can still deliver a special kick.

Curiously, few other publishers take advantage of this color-coded declaration of importance. Even Nintendo hasn’t dipped into this well often; Mario games will sometimes be coated in red, and Pokemon games match their respective sub-title, but few other franchises command the same link (pun intended) between color and content.

Since CDs became the dominant format medium, games were stuck inside a system’s casing, spinning, unseen by the players eyes. Special packaging of deluxe and collector's editions are now focused on elaborate boxes and unusual extras-- cat helmets and snow globes and risque mouspads. There's little effort to make the physical object that the game resides on look special. PC game publishers had the same issue; whether floppy disc, CD-ROM, or downloadable code, few games remained visible during play or after.

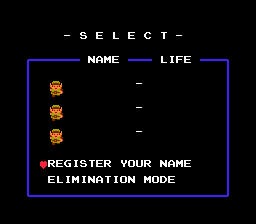

The idea was always to save the kingdom. Saving your game, on the other hand, was an anachronism from the future, an idiom that meant keeping your cartridge in the box and storing it safely in your parent’s cupboards.

But The Legend of Zelda changed this. A holdover feature from the Japanese version’s Famicom Disk System release, installed in every copy was a small battery that allowed the player to automatically freeze their progress as they adventured through Hyrule.

Prior games required you to copy down a long string of numbers and letters that the software would then recognize as a placeholder. Too many times, Os looked like 0s and 1s looked like ls.

Would a warrior forget where they were? Would the Hero of Time lose track of his gathered rupees, drop his shield behind the couch-cushions, misplace his sword on the way to the healing fountain? No.

We take the ability for granted now. Most modern games auto-save. PCs have long allowed, from a system-level, the ability to pause and continue from that point later on. But The Legend of Zelda brought on-cartridge saves to consoles, jump-starting a new normal. ��“Zelda was an evolutionary step up,” says Popcannibal founder Ziba Scott, co-creator of Girls Like Robots and Elegy for a Dead World.

More than simple convenience, the cartridge’s battery gave this object something most other games did not: Memory.

“It remembered,” says Scott. "It’s not just a dead, static thing. It was alive. There was a world in there.” Playing The Legend of Zelda at a friend’s house sold him on the NES; when he returned home, his Atari 2600 looked feeble.

Saves also mean that each cartridge was unique--yours was not the same as your friend’s. These were not swappable, identical hunks of plastic; the time you spent and the places you saw were all recorded, waiting for you. Even without the glimmering gold casing, the cartridge was your own personal artifact from an arduous quest.

You May Also Like