Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Trying to bring innovation to the genre of music games costs you a lot of time, even more nerves and mostly feels like tilting at windmills. So what's the matter with this highly polarising videogame genre? Here are my thoughts.

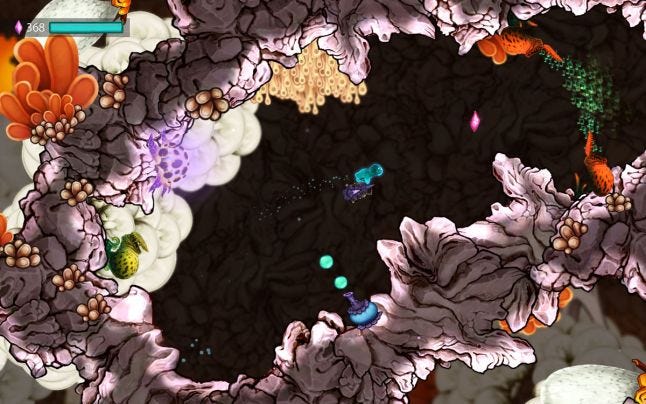

This article focuses on the cons of developing music games. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a wonderful genre. Otherwise we wouldn’t have spent the last four years developing a non-linear music-action-adventure. Nonetheless, creating a music game always comes with several downsides, which might be surprising for some developers. Based on the experiences we made with developing »Beatbuddy: Tale of the Guardians«, I want to highlight those issues and give developers a subjective, different and honest view on this polarizing videogame genre.

Whenever we pitched Beatbuddy to other developers or press over the last few years, it was always basically the same story. At first glance, they all liked the look of the game with its 2D hand drawn graphics and the charming main character Beatbuddy. But when we started to talk about the fact that Beatbuddy is also a music game and how each level is based on a song, you could see their attention fade away – or maybe even worse – drift off toward totally wrong expectations. It’s like mixing somebody a nice cocktail and then spitting in it. Why are the words »music« and »game« such a problematic combination?

The first big problem is that core players don’t expect to see any innovation coming from the genre of music games. Because of countless rhythm games with basically the same concept, the expression »music games« became equivalent to the word »casual«. The »Guitar Hero« games, »Rockband« titles and all the other clones that followed might have been a great financial success in the past, but they ruined the reputation of the entire genre.

It almost feels like music games are not in the club of »real« games. We’re facing a »Justin Bieber« situation here. There is only a small amount of people saying that Justin Bieber is OK. The majority of the people either love or hate him. And the more Justin does Justin stuff, the more fans will love him and haters will hate him. We have a missing middle ground, a layer to connect.

The resulting gap between those two opposed fronts is a strong indication of unexplored video game design territory waiting to be discovered: the promised land of music-gaming hybrids.

That’s why we packed our bags four years ago and decided to create the first musical action-adventure with Beatbuddy. We hoped to mix the best parts from black and white without ending up with grey. On our journey of genre-balance we came across a few like-minded titles. Games like »Sound Shapes«, »140«, »Fract OSC« or »Crypt of the Necrodancer« underlay solid core gameplay with musical elements. All titles feel refreshing and are great games. But only a small audience is even aware of their existence.

In my humble opinion, this is a direct result of the prejudices that music games are facing. Especially games that try to bring innovation to the genre have a very small audience to talk to, somewhere in the middle of music game fans and core gamers.

Typical features that fans of the genre expect to see in a music game, which is at the same time a list of reasons for other gamers to avoid the genre.

Feature | Music Game Fans | Rest of the Gamers |

|---|---|---|

Rhythm based mechanics | Gets you into the groove | Repetitive and boring |

Procedural generation / powered by your music | I can play the game to my favorite music. SWEET! | Here comes Mr. generic gameplay |

Connecting with the cultural world of music | Nice I’m holding a guitar | I’m not a musician, I only act like it |

Entertain other people / socialize | Look at me, 100k points! | Look at me, I’m making a fool of myself |

Synesthetic experience | Dude I’m tripping | I’m getting dizzy |

The biggest problem is that this audience gets even smaller after the second issue I found with music games.

We all have a very different taste in music. That is awesome and also the main reason why we have such a big diversity of musical genres. But that’s another killer for music games because your game might have the »wrong« music for your audience. For example: you created an awesome game, but if people associate it with a certain music genre like Rock, Electro etc. they will very likely back off without even giving the game a try. That is a terrible thing, but it happens a lot.

We thought we were smart with Beatbuddy and got a wide variety of songs produced from Electro-Swing to Rock music. But nonetheless we got very diverse press feedback, depending on the musical taste in each region. In the US and UK for example, where electronic music is king, Beatbuddy’s soundtrack always elevated the ratings. In Germany, where Rock is the dominant music genre, our ratings mostly suffered from our electronic titles in the game.

One way out of the »taste in music« debate is to use the most generic music you can find to ensure that nobody will feel offended by it. »Elevator music« is probably the most fitting term. But if the music doesn’t matter to anybody and is totally interchangeable, then why should you make a music game in the first place? I think it’s important to be aware of this issue and pick music that fits the overall feeling of your game.

This is actually my favorite point on the list because it always reminds me of how naive we were with Beatbuddy. This is how we, back in 2011, hoped music licensing would work:

You get in contact with the music artist whose song you desperately want to get

You ask for the song

You find a deal

You use the song in your game

The plan was to partner up with »music industry« musicians and utilize their fan base to attract additional players. Since we had no money to pay for licenses up front, we wanted to offer a share on our game revenue. Furthermore, we thought it would be an amazing plan to cross-promote their music through our game and vice versa. That sounded like a win-win situation to us.

It took us almost two years to find out that this plan wouldn’t work that way. The main issue is that co-operations between the gaming and music industry are relatively new. It takes a lot of time to make each side understand how the other industry works.

I will try to give a little crash course on the music industry and the parties involved in the process of licensing a music song.

The whole commercial exploitation cycle always starts with the production of a new song. Naturally, all rights to this song belong to the musician who produced it. But since the music business is rather complicated, most artists outsource their exploitation rights exclusively to music labels, publishers and collecting societies. Therefore you will likely deal with one of those parties and not with the artists directly.

This will only apply if you want to license music from outside the gaming business. Most video game composers hold all their rights to themselves because they wouldn’t be able to compete on the market if they stuck to the rules of the »normal« music industry, but I will get to that later.

A publisher in the music industry has a very different position compared to a publisher in the gaming industry. Instead of marketing and distributing a final product, a publisher holds the rights on the original composition of a song, which includes the notes, lyrics and so on. The rights on an actual mix are exploited by music labels. In most cases you still need to talk to the publisher, because if you combine an image or video with a song, you change its context and need permission from the publisher. By the way, the combination of a video and song is called »Synchronization« and is the basic licensing you will need for using music in a video game. Synchronization includes talking to the publisher and label.

In rare cases, developers only deal with the publisher. For example: all songs in »Guitar Hero 1« have been re-recorded with cover bands since the developer couldn’t find a deal with the music labels. After the great success of the game, the developer switched to the real mixes of the songs for »Guitar Hero 2«.

Labels in the music industry are equal to publishers in the gaming business. The three major labels are Universal, Sony and Warner Music. You can compare them to companies like EA, Ubisoft or 2K. They hold the rights to actual mixes of the songs and the purpose of those labels is to distribute the titles and market them. Furthermore, live shows and merchandise are big deals for music labels.

If you want to license a song from a known artist, you need to have a lot money on your hands. Apart from that you need to make sure that you’re talking to the right people since you want worldwide clearance for that song. The music industry is still very focused on regional bands and artists, so a worldwide clearance is not everyday business.

When talking to a major label, you’re very likely to get the following type of conditions offered for licensing a song: non-exclusive, worldwide clearance, usage for five years, royalty on sales and an advance fee deductible on sales. Since you’re planning to do the industry a favor by promoting their music through your game, it will shock you how high this advance-fee will be. From a financial standpoint, it’s not worth it. The amount of additional units you will sell won’t be equal to the amount of money spent to license the song.

Another way to get the music for your game is to partner up with a label and plan on a cross promotional campaign. But just like in »Guitar Hero«, you can only go for that strategy if you’ve proven to have a successful product on your hands. Otherwise it’s impossible to discuss a fair deal.

Collecting Societies

Since the music industry became really, really complicated over its 100 years of existence, most labels, publishers and musicians are part of a collecting society. Those societies make sure to collect money whenever a song was aired or distributed. Each country has different collecting societies and different membership rules.

I will explain the situation on the German collecting society called GEMA, which has a somewhat monopolistic position in Germany. If an artist is part of the GEMA, all the distribution rights of his music get transferred to the institution. So if you want to license music from that artist you need to make the financial deal with the GEMA. The collecting society has a big catalogue of rates, depending on the way you want to use the song. The problem is that the GEMA doesn’t have any rates on the »new« business models like digitally distributed video games or music streaming services.

If you’re from Germany, you might have seen that you’re not able to watch certain videos on Youtube. That’s because the GEMA and Google were not able to agree on how much Google has to pay for each streamed music video. That’s not only terrible for the consumer, but for the artists as well: they are not able to promote their music in Germany.

I mentioned in the beginning of #3 that most musicians in the gaming industry neither are part of a collecting society, nor do they have a publisher or label. The reason behind that fact is that if you’re part of the GEMA, you can’t do a so called »Buy Out« with your music. Each time a copy of the game is sold, the distributor would need to pay a fixed rate to the GEMA. For Germany, this could be between 7-9 cents for each song used in a digital game.

The problem is that this rate is not the actual rate. As I mentioned before, there is no rate for digital video games. Therefore the GEMA holds the right to pick the closest fitting rate. In this case, video games are compared to digitally sold music. The average price of a song on iTunes is 99 cents. 7-9 cents seem fair in that case.

However, the average price for a mobile game is also 99 cents. And if that game contains maybe 6-10 songs, the rate of 7-9 cents suddenly doesn’t seem fair anymore. You actually lose money whenever you’re working with licensed music in your game.

Another problem with the GEMA is that artists who want to work with you and give you a different rate are not allowed to do so. Once an artist signed up with the GEMA, they are bound for life. This means that no GEMA artist is able to make deals with the video game industry.

However, this entire thing also works the other way around. If you’re a composer of video game music and a big label wants to sign you to introduce your music to a broader audience, you’re forced to be part of a collecting society. It’s unethical to work with musicians who are not secured by a collecting society because they can be easily cheated with »Buy Out« deals and such.

This means that as a musician in Germany, you basically have to choose for the rest of your life for which medium you want to produce music. I know that not all collecting societies have such strict rules. Teosto for example, a big collecting society in Finland, has worked actively with musicians from the gaming industry to address this problem. They made it possible to license music under special conditions to certain partners. In the US, this problem is not as imminent as in Germany since none of the collecting societies really hold a monopoly on the market. Furthermore, collecting societies in the US are way more flexible toward the economic needs of the industry.

If you’re planning to use music for your game and want to avoid frustration, I can give you two pieces of advice:

Talk to the artists, don’t talk to the industry!

Don’t use licensed songs!

After taking a trip to the dark side of music industry collaborations, it’s time to talk about music game design. This could be the main reason why people develop music games after all, because they are easy to make. This assumption might fit to certain types of rhythm games, but if you’re working on any form of musical hybrid, this perception is wrong.

For Beatbuddy, we basically had to design two games in one. All game mechanics were designed under two major criteria. They needed to:

Visualize music

Deliver meaningful gameplay

This was actually way harder than it sounds because we wanted to come up with unique mechanics that hadn’t been used in music games before. One rule was: no rhythm mechanics. Everything was supposed to be accessible and enjoyable without forcing the player to do things in rhythm. After following that rule, we had a set of basic mechanics.

Since Beatbuddy was developed over the course of four years and throughout four different prototypes, it took us a lot of iteration to find the right balance between music visualization and gameplay.

Furthermore, we wanted to be the first game in which the player could move forward as well as backward in a song. The mechanics and level design were deduced by the structure of the song itself. As the song got more complex with multiple instruments playing at the same time (high hat, vocals, snare etc.), the level design had to reflect it.

This is why we decided to have different gameplay parts for the verse and chorus. In the verse, you can move freely as Beatbuddy, solving action-adventure puzzles and fighting enemies. In the chorus you would drive in the Bubblebuggy, moving only to the beat of the bass drum and snare. The Bubblebuggy parts, in which most instruments are playing, feel way more »arcady« and help to loosen up the gameplay.

Till we found out that a mix of those two gameplay styles would help us to keep the player engaged, we had already spent two years on the game. Our mission to »design a music game that is not a music game« gave us a lot of headaches. Especially since we had no real examples of how such a game is done properly.

Another reason why it’s so hard to design a music game is that you’re facing a lot of technical problems. One of them is the behavior of the players. If you’re talking about mobile or browser games for example, only a few people even have the sound turned on while they’re playing. Therefore your game needs to be designed to be playable with and without music.

Furthermore, musical data is really heavy on disk capacity. In Beatbuddy, we worked with stems to visualize each instrument in a separate game mechanism. Each song has about 8-12 stems and we have six songs in our game. On mobile devices, that will lead to a lot of data weight. And the bigger the download-file, the less people will install your game.

If you’re just using an mp3 file for your game, you’re not really able to play with the different parts in the music or generate a convincing visualization. Due to the high compression of the file, you can basically only filter out the beat and certain sound peaks.

When your game requires a more precise visualization and you have access to the stems, there is still a lot to consider. It’s extremely difficult to make sure that all animations are on the beat and that the different sounds stay in the rhythm. The music has to sound and look awesome even if you’re having occasional performance problems.

For Beatbuddy, we were forced to develop a completely new sound technology, which went patent-pending in March 2013. With this technology all animations are precise to the millisecond. We can even hook up sound files to game-mechanics and create suiting behavior and animation in real time. This technology really helped us to speed up our production, but also cost our CTO Erich Graham two years of development. Luckily, our technology is not that hungry on performance, but of course it’s more demanding than just playing a sound file. It’s important to keep that in mind when you’re planning the memory usage of your target system. You might have to cut down on some graphics to keep your frame rate above 30 fps, for example.

This article was supposed to give an overview of the problems that music game developers are facing. I think the worst about the genre is that it requires a lot of technical skills as well as a broad understanding of the music industry to develop music games. Because of genre prejudices and a rhythm game stigma it’s hard to make those titles a commercial success. This imbalance makes it a tough choice to develop innovative music games, but on the other hand, it’s tempting to come up with something new in this high potential genre.

I think it’s important to understand that you develop music games out of idealism and not for money. Don’t make unnecessary expenses on music licenses and big music industry partnerships. Work together with young indie musicians and contribute to this fun game genre. There is lots of game design territory waiting to be discovered.

[Originally posted in Making Games Issue 01/2014]

Beatbuddy: Tale of the Guardians is available on STEAM for PC and Linux

THREAKS is a small game studio from Hamburg Germany. Meet us at GDC SF 2014 for beer or burgers, or both. We tell you all about Lederhosen and Bratwurst.

And if your a social person you can follow THREAKS on Twitter and Facebook.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like