Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra checks in with some devs from around the industry to highlight some key games in the genre that all developers should study, in an effort to understand the strengths of the immersive sim.

Ever since Looking Glass Studios' seminal 3D role-playing game Ultima Underworld (1992), the immersive sim has been held up by its proponents as a game design ideal.

Notably, these games tend to espouse an ethos built around the idea that a player should feel like an inhabitant of the game's world — with all of the freedoms that would entail.

And while it has tended to come in and out of vogue across the industry since its inception, the immersive sim is definitely enjoying a bit of a renaissance right now — with Prey and Dishonored developer Arkane at the head of growing wave of immersive sim disciples and admirers.

With that in mind, we thought it'd be good to check in with some devs from around the industry to highlight some key games in the genre that all developers should study -- whether you're making an immersive sim or not -- in an effort to understand the strengths of this school of game design.

Co-directed by one of the pioneers of the genre, Dishonored and Dishonored 2 are perhaps the best modern examples of the immersive sim (although some may argue that Prey has outdone them).

Consortium lead designer Gregory MacMartin considers the level design in the Dishonored games to be especially notable. "It represents the bleeding edge of seamlessly combining gameplay possibility spaces and believable / aesthetically pleasing architecture," he says. "The level of agency these games give players to approach situations in multiple ways is genius."

Dishonored values freedom. Players can play it as a stealth game and endeavor to either avoid confrontation or to incapacitate or kill enemies without detection, and in the process to soak in the world and the atmosphere (it's actually possible to complete the game without killing anyone.)

But they don't have to, as there's always the option to go out guns blazing and tear through levels as though stopping would mean death. Or to embrace a style anywhere between these two extremes, perhaps with help from the many inventive steampunk-meets-magic gadgets. And in keeping with the ideals of immersion, MacMartin notes, actions have consequences — the story changes, and the endings vary, according to how the player approaches the game.

TAKEAWAY: Giving players full agency to play how they want takes two key design considerations: on the one hand, a diverse, inventive suite of tools and verbs, and on the other smart level design that allows freedom to solve problems in any way the player can imagine.

MacMartin feels that Deus Ex has aged poorly, especially in terms of its narrative, but Eldritch and Neon Struct designer and former 2K Marin programmer David Pittman thinks it's still an important game to study — for its enormous ambition, if nothing else.

It fuses genres and throws together an action/thriller-style globetrotting adventure with the player always pushed to play around with a feature set that Pittman believes "dwarfs every other immersive sim before or since."

"What I've always found fascinating about Deus Ex — and why I believe it works so well, or at all — is that it is consistently inconsistent with its available options," says Pittman. "Deus Ex's systemic palette is undoubtedly broad, with sneaky bits and talky bits and action bits; but in practice, the balance of those elements shifts considerably from moment to moment and from mission to mission."

By varying the situational context — the level design and scenario and available tools — Deus Ex is able to remain dynamic, to encourage players to keep experimenting with new solutions and strategies. The lesson here, Pittman believes, "is that a broad player toolset is not interesting per se; the exciting stuff happens at the intersection of the player's available tools and a particular challenge."

TAKEAWAY: Consistency does not mean always offering a full suite of options, or even necessarily allowing the same solutions to always work; rather, it's in following the rules of the world, and if you're smart about it it could involve setting expectations that experimentation will be rewarded more so than rote behavior.

MacMartin argues that the original Thief has been surpassed by the likes of Dishonored and Prey, but he concedes that its hiding mechanic (stick to the shadows and the guards won't see unless you're loud) "remains genius" while its use of banter between guards that players overhear when sneaking around in the darkness is a great technique for building narrative context.

Pittman praises Thief's "almost tangible" sense of place. "I think Thief's distinguishing factor is the way its technology and mechanics harmonized to make players pay attention to the physical space of its levels," he says. The sound propagation, hard and soft surfaces, and light and shadow all worked to the benefit of both the stealth mechanics and the mood and immersion of the game, Pittman notes. And they also showed that the ideals of the immersive sim genre could be applied with only a small palette of player verbs, enemy behaviors, and quest structures.

"Where other immersive sims before and after it show their roots in tabletop and computer RPGs," says Pittman, "Thief dispenses with skill points, player builds, and NPC conversations to focus on the core simulation of sound, light, and AI awareness. Thief II: The Metal Age mostly leaves the formula alone, but its superior level design reflects a team with a clearer vision of what they were making."

TAKEAWAY: Less is often more in game design; by focusing on a smaller set of ideas, systems, and verbs, Thief establishes a world dripping with detail and carefully designed around physicality — space, sound, light, dark, and movement bring depth to its relatively simple set of mechanics.

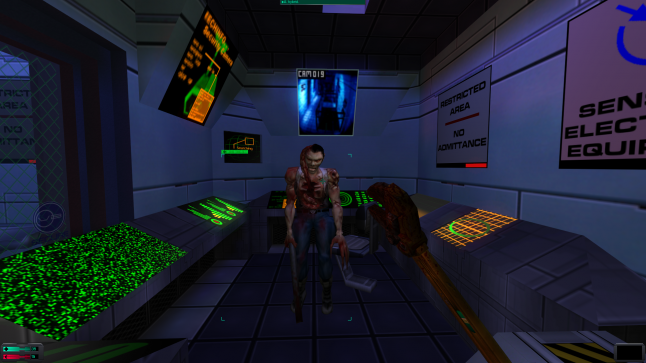

"System Shock 2's mechanical scope is broader and looser than Thief's," says Pittman, "revealing more of the RPG influences of the genre: player classes, skill points, inventory management." Its levels are at times akin to an open-ended playground, and its balance wavers in many places, but System Shock 2 remains important both for its influence and its high points — its captivating horror story and excellent sound design along with its flexibility in accommodating multiple play styles and its tactical depth.

It's a game about helplessness and powerlessness, every decision — every puzzle and challenge — open to a multitude of inventive solutions that can then be twisted around to further accentuate that sense of vulnerability — especially once the formidable, malevolent AI SHODAN reveals herself as an antagonist with a twist and begins to relentlessly taunt the player.

"And hey," adds Pittman, "this is a game in which the player can collect a gaming device and cartridges, and play an Ultima-esque RPG within the UI."

TAKEAWAY: The systems-heavy interactivity and freedom at the core of immersive sims can just as easily be used to stifle and undermine as to liberate and empower, if paired with smart writing.

Developer and academic Robert Yang suggests that early access game My Summer Car might be the best showcase of where immersive sims are headed next. "It's very specific," he explains. "It doesn't try to simulate an entire city, but instead it goes very deep on one thing (a car). It also doesn't explain itself at all. It feels mysterious like the old Minecraft beta."

Indeed, players begin the game knowing little more than the fact that it's a permadeath life simulation set in 1990s Finland in which they attempt to build a car from scratch and then tune/fix/maintain/drive it, all while taking care not to die.

And in typical immersive sim fashion, it makes no attempt to help the player learn any best practices or ideal ways to play. Instead, the player is left to their own devices in how they learn and approach the systems and how they solve problems. It's immersive sim design taken more literally — a chance to become a person in a particular time and place as they embark on a specific project and enjoy a carefree summer.

TAKEAWAY: Immersive sims don't need to have sci fi or fantasy themes; they can be set just as easily in the life of an unextraordinary person in decidedly ordinary circumstances.

Pittman thinks Arkane's oft-overlooked debut title Arx Fatalis — which he calls "a sequel-in-all-but-name to Ultima Underworld" — deserves more attention.

"Like the Underworld games," he explains, "Arx Fatalis is firmly rooted in the RPG genre, blurring the line between immersive sim and first-person RPG." It's an atmospheric dungeon crawler with twisting tunnels and sprawling labyrinths filled with fine details that make them seem lived in as the player slowly gains familiarity with these intricacies.

"Where it shines for me," adds Pittman, "is the design of its world: a rich, densely packed, intricately interconnected 8-story complex that unfolds more like a Metroidvania than any other title in this list. There's a je ne sais quoi in the gradual discovery and mastery of a space, which I feel is an important yet rarely discussed aspect of immersive sims."

TAKEAWAY: The beating heart of an immersive sim is its world — make that feel tangible and rewarding to simply exist in and you'll have achieved much of the central ideal of the genre: the sense of immersion in one's virtual surroundings.

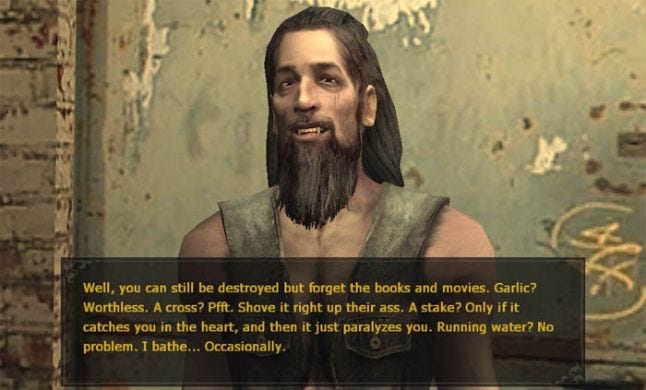

Once described in PC Gamer as "the best immersive sim ever made, if its developers had been given the time and resources to finish it," Vampire: The Masquerade: Bloodlines remains an essential immersive sim, in spite of its many rough edges, for the way players can personalize their experience within its moody world of gothic horror and vampire secret societies.

Like all immersive sims, it offers a spectrum of solutions to problems (although all involve violence, in one form or another), but it differs to most in stressing direct communication as a key means of interaction — with separate skills dedicated to the arts of persuasion and seduction, as well as to haggling and intimidation, that all affect conversation options — and in forcing players to watch that they don't become too much of a monster, lest they face grisly consequences.

Dishonored gameplay programmer and Question co-founder Kain Shin points to one level in particular as worthy of attention: The Ocean House.

"By the time you get to this level, you are pretty much unmatched in your use of weapons and powers when it comes to enemy threats within the game," he explains. "Monsters just don't scare you anymore because you know exactly what they are and you know exactly how to defeat them. The Ocean House hotel takes you back to the basics of fear by making everything feel unknown again, and that is why I remember this level... my overpowered Malkavian felt vulnerable, once again, even if it was all just an illusion made up of parlor tricks."

It's a short level, but Shin thinks it's just long enough to break the pattern: "It isn't long before you realize just how much the in-game enemies served as a source of comfort by feeding your power fantasy within the game," he says. "Unlike the rest of the game, this lonely abandoned hotel leaves you with a constant feeling of dread by taking away your sense of certainty."

TAKEAWAY: Artful use of scripting can configure and reconfigure player expectations, even in games that prize player freedom and emergence.

Immersive sims may share certain common ideals, but they need not take the same route to achieving them. Breadth or depth, systems-driven or scripted, non-linear or mostly-linear — it doesn't matter, so long as the world is cogent, reactive, and inhabited and the player has the freedom to tackle challenges however they see fit.

There's value, too, in looking to the periphery of the genre — to open worlds like S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and, further afield, The Witcher 3, and to shooters like Bioshock, narrative adventures like Tacoma, and survival games like The Long Dark, that draw on the ideas of immersive sims (whether they themselves fit the definition or not).

Bioshock is a masterclass in believable world design, for instance, with narrative and level design that cleverly allowed player freedom while simultaneously restricting player agency. The Long Dark and S.T.A.L.K.E.R. are superb showcases of systemic hostility — of an environment that seems inclined toward entropy. The Witcher 3 is so dynamic and open-ended and full of consequence that it feels remarkably believable as a place, in spite of its limited set of player verbs.

The immersive sim was never a distinct genre — rather more of a philosophy or design ethos that tended to find its way most often into first-person shooter/RPG hybrids. Remember: there's no reason why an immersive sim needs to be set in a sprawling violent world, or to include fantasy or sci-fi elements. An immersive sim can be anything so long as it's consistent and reactive and its world feels alive.

Thanks to Gregory MacMartin, Robert Yang, David Pittman, Kain Shin, and Michael Kelly for their help putting this list together.

You May Also Like