Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this feature, former console audio director turned mobile and browser director Brad Meyer explains what challenges are presented by these constrained platforms -- and how to get the best results with the tools, budget, and staff size that's required by them.

[In this feature, former console audio director turned mobile and browser director Brad Meyer explains what challenges are presented by these constrained platforms -- and how to get the best results with the tools, budget, and staff size that's required by them.]

The past couple of years have seen an explosion in small, free-to-play games, primarily on the web and mobile platforms. These games' pedigree is reminiscent of the early years of video gaming: smaller, innovative titles made by very small teams, often no more than a few people.

While we have seen some of these titles push gameplay mechanics into new and unique realms, the audio in this burgeoning new sub-industry is not quite keeping up with the innovation. The reasons are understandable: small teams with little or no budget rarely have room for the "luxury" of a full-time sound designer, let alone a composer or audio programmer. Also, designing games for the web and mobile platforms brings us back to the challenges of dealing with very finite disk space and more severe hardware limitations.

This article aims to address these issues and present ways to overcome them in order to boost overall audio quality in the growing browser and mobile gaming markets.

Perhaps the most ubiquitous challenge facing new developers in the mobile and browser realm is team size. Gaming is entering into a cycle of rebirth in these fields (thanks mostly to minuscule budgets). 100+ size teams are being replaced with a couple dozen, or fewer, dedicated developers.

As a result, most teams forgo costly proprietary game (and audio) engines in favor of a third party engine such as Unity, Flash, Unreal, Torque, or ShiVa.

Relying on these existing engines gives teams a head start, in that they do not have to reinvent the wheel and can start building a game with a toolset already tailored for their platform(s) of choice. With smaller teams, we see simpler games, but also less specialization and greater generalization in tasks.

As an audio developer, you must therefore become the Swiss Army Knife of all things audio. While I could rant for several thousand words about the importance of a dedicated audio person on even the smallest team, let me be brief so I can get off the soapbox and back to making sounds.

Most small teams working on mobile and browser games believe that they do not need a dedicated audio person on the team. They can outsource some sound effects and have a programmer or designer put them in. I would agree if the same were done with animation, art, and code. However, in even the smallest teams, there is at least one person from each discipline in-house to ensure the quality bar is being met and things are looking/behaving/sounding as they should.

If a game wants to be of the highest quality, then it must shine in all areas, including audio. For audio quality to catch up to consoles, someone must be involved in the oversight of all aspects of audio for a project. This individual must be passionate about good audio and devote all his/her energy to it (just as an art director ensures the graphical quality of the game meets expectations).

A jack-of-all-trades in each discipline is often necessary on a small team, and while it requires a huge skill set, it helps the team tremendously. Without a dedicated sound person no one would have the appropriate bandwidth to keep an ear and eye on audio.

Furthermore, a sound person can make him or herself indispensable by allowing other departments to focus solely on their own tasks. Animators can focus on animating and the sound designer can place animation event sounds. Level designers can focus on building the level while the sound designer hooks up the ambience, level event sounds, etc. A dedicated audio person may expand team size, but s/he will also increase quality of the entire project, allow others to focus on their respective disciplines, and keep a necessary ear in production. Okay, sermon over. On to the sound!

Due to smaller team sizes, sound designers cannot necessarily rely on having an audio programmer or audio implementer putting their sounds into the game and getting everything sounding great. Most game engines provide a scripting language for control over in-game playback and parameter control. If you are not using a separate audio middleware solution (and often if you are), these languages will be one of the main keys to getting your game's sound to shine.

So for better or worse, one of the first tips I have for a sound designer in a small company is to learn scripting. The most important part of a great sounding-game is creating great sound effects. The other big piece of that puzzle is how the sounds are handled within the game engine, and control over this is most often through scripting.

Naturally the scripting language of the engine you are using will be most important to you, but the beauty of scripting, and most programming languages in general, is once you understand the flow and syntax of one it's relatively easy to pick up others. Unfortunately there is not a lot of commonality across popular engines: Unreal uses proprietary Java based UnrealScript. Flash has JavaScript related ActionScript. Unity supports JavaScript, C#, and Boo (an offshoot of Python). The Torque engine uses a C++ based language called TorqueScript. ShiVa uses Lua, etc., etc.

The hardest part about learning a scripting language is getting started. I learned scripting in a multi-stage process: I was fortunate enough at my previous studio, Shaba Games, to have our technical director, Robert Morgan, and the programming team give classes to designers to help them get familiar with basic scripting principles. He also pointed me to this website: Pinky and Brain learn C++, which, cheesiness aside, is probably the most helpful, straightforward guide to teaching basic scripting and programming fundamentals.

From there, it became a matter of reading reference materials, experimenting, and looking at other people's code. A very helpful tidbit I learned from programmers early on is that using someone else's code and tailoring it to your needs is not so much stealing as a way of life. Forums and online communities, which we will discuss later, are also a great resource for direction and help when getting your feet wet in the world of scripting.

Scripting is not for everyone. It takes dedication and time to wrap your head around the concepts of basic scripting and then the unique functions, syntax, and idiosyncrasies of whatever scripting language your game engine may use. However, the time and energy invested in learning how to control your sounds' behavior will pay back dividends throughout the rest of your career. We need to be able to create complex audio systems such as occlusion, dynamic ambience, and interactive music that are common in consoles and can push online and mobile game audio to the same level. All of these systems can be created via script in most modern game engines.

While scripting is inherently necessary in most engines, some do offer GUI components for tweaking certain parameters. Whether it's building sound behaviors, setting attenuation curves, or even doing complex visual scripting such as Kismet in Unreal, these are welcome additions to the sound designer and can occasionally replace the need for scripting.

As I briefly insinuated, it would be unfair to expect a sound designer to pick up scripting and suddenly be an audio programmer. This is a huge challenge for smaller studios, and a potentially tremendous difficulty in building an audio system with features one would expect on a console.

Enter one of the most beautiful, populist means of social interaction and idea dissemination in the information age: the community forum. Most engine providers support a forum or email list designed to help users solve problems collectively. Having been involved in both Unity and Unreal's forums, I have repeatedly seen people from competing companies help each other solve problems and share techniques. The end result is that everyone's game is improved through friendly cross-corporate cooperative spirit.

In regards to audio, there are people out there who can help provide insight into setting up scripts or tools to do what you need. You should never approach these forums expecting someone to write an entire system or script for you, but participants can be very helpful in pointing out issues you may have or problems you may have overlooked. It is usually just a matter of asking around, being patient, and learning from your colleagues.

One person being in charge of all sound effects, music, and audio programming is a tall order, no matter the scope of the project, which is why contractors were invented. Having a dedicated audio designer does not necessarily mean you can expect them to handle every task related to audio.

Just like other disciplines, it is often necessary to outsource certain elements of a game to maintain quality and make deadlines. In the scope of the project, outsourcing a component (be it weapons sounds, music, dialogue editing, localization, etc.) can be an efficient means of raising the sound quality bar while keeping costs reasonable. At the same time, having an internal audio designer gives the team someone to manage the relationship with the contractor(s), provide direction, and accept, reject and integrate assets.

An even greater challenge for pushing the audio envelope of browser and mobile games is file size. In these titles we are dealing with a very finite amount of space in which all data must reside; an amount that is minuscule compared to a Blu-ray, or even a DVD. So how do we pile on the variations and high quality assets that will make our game pop and sound great given this limitation?

Perhaps the single most revolutionary breakthrough in digital audio in the past 20 years was the invention of high compression, high quality codecs. Being able to compress a PCM file to one tenth or one fifteenth its normal size without noticeable artifacting and acceptable frequency response is really what makes console quality audio possible on smaller platforms (and even consoles for that matter!)

While compression is a modern miracle for cramming sounds into your game, it is still a matter of weighing quantity versus quality. Most game engines with support for browser and mobile platforms use either ogg or mp3 as the compression format of choice.

In both of these codecs, the lower the bitrate, the lower the quality and the smaller the file. It is the sound designer's job to figure out where that sweet spot is on the bit depth/file size matrix for their sounds.

For better or worse, when dealing with browsers, cell phones, and tablets we are not talking about audiophile 5.1 systems, so it is a bit easier to err on the side of lower bitrates without overly compromising sound quality.

For example, in Unity, I compress most of my sounds at 56kbps ogg (roughly quality 0) which translates to 14:1 compression and gives me acceptable quality on every set of speakers I've played through, from Dynaudios, to laptop speakers, to headphones.

Another tip to remember when dealing with ogg and mp3 compression is that from a file size perspective, stereo sfx are virtually "free." There are a couple different ways compressed audio handles stereo files, all of which keep the file size very close if not identical to a mono file of the same length.

The best quality stereo files in these compressed formats are Joint Stereo, which is a means for the codec to selectively compress in a way that maximizes the stereo effects of the sound without reproducing extraneous data. I like to use stereo sounds for my UI sound effects to give menus a bit more audio character, and am able to do so without fear of weighing down the overall audio footprint.

Another important point in regards to compression is to always keep your source files at the highest possible sampling rate. These codecs handle downsampling themselves, so a 12kHz WAV file compressed to a specific bitrate will be the same size as a 48Hz file post-compression, but with one quarter of the sonic data. Downsampling before compressing is a sure fire way to make your game sound muddy and should be avoided at all costs. As a rule of thumb, I design all sounds at 48kHz and import them into the engine at this rate, letting the compression parameters I set within the engine dictate how small my sounds will get.

Optimization is another very important factor when it comes to making great sounds for smaller platforms with smaller memory allotments. Being cognizant of file size throughout development can help you be judicious in your optimizations. Simple tasks like cutting unnecessary tails from your wave files, limiting variations, or reducing the bitrate/quality for lower frequency sounds all seem mundane, but can make a cumulative difference in the end.

A final note should be made in regards to compression and optimization when dealing with looping mp3 sounds on mobile platforms. This can be a source of endless frustration for most sound designers in that your engine MUST be capable of compensating for the sample padding generated as a result of compressing to mp3.

When an uncompressed file is converted to mp3, the compression algorithm adds samples to the sound file which make seamless loops impossible. Many engines offer their own way to circumvent this issue (Flash, Unreal and Unity 3.2 and later all do.) However, it can be a very frustrating technical hurdle to get around if you are not aware of it and your engine does not support gapless looping. For more information on this issue see PJ Belcher's article on iOS Audio Design.

Similar to consoles, if we want to get longer sounds, such as music, dialog or long ambiences playing in our smaller games, we need to stream them. Streaming has historically been off the physical media of a console or PC (hard drive, CD-ROM/DVD/console disc, etc.). We still use the same methodology, except now our common sources to stream from are either the physical media (a hard drive on PC and SD-cards or other removable memory sources on mobile devices) or from the internet.

When thinking about what sounds are appropriate to stream, there are several factors to consider. Perhaps most importantly is, where are we streaming from? Streaming from physical media is quicker as far as response time if latency is a concern, and also significantly more stable since network traffic can be disrupted much easier than the communication between a device and its storage medium. Online games can fight for bandwidth with both networking and streaming going on. Streams can drop if there's a network hiccup, or not buffer in time to begin when they need to.

On the other hand, streaming from the internet allows for a smaller initial (or shorter incremental) download of your game. It also allows a smaller overall footprint and the potential ability to dynamically update or alter content by uploading audio files to the internet and patching a single script rather than needing to append whole compressed audio files or package files.

Some engines even allow for multiple streams to play simultaneously opening up the possibility of sophisticated multi-stream scenarios for dynamic dialogue, surround ambience, interactive/dynamic music or other creative uses. In short, you have much greater flexibility with online streams, but greater stability from local streams.

Streaming can be a complicated scripting affair or a matter of checking a box depending on how you want to stream and what options your engine offers. The methodology often differs if you will be streaming from disc versus from the internet, and some engines only offer one solution or the other.

There is a time and a place and special content ripe for streaming. It is up to you to decide the most prudent way to stream and what content should be streamed. Regardless, streaming can be an excellent means to showcase long dramatic sounds in your game that would not otherwise be possible.

A very important and so-obvious-it's-easy-to-overlook way to get the most out of sound on a mobile or web platform is to be creative.

Early sound designers were making an unbelievable array of sound effects and musical instruments with nothing but square waves and noise generators.

While we have refined consumers' tastes and expectations over the years and have more tools and capabilities now, we must still use our brains to figure out ways to make sounds interesting, evolving, and efficient.

When dealing with looping sounds on mobile and web platforms, we often need to err on the side of smaller file size. Modulation is a surefire way to get the most out of small looping files so that they evolve and change over time without getting stale or annoying.

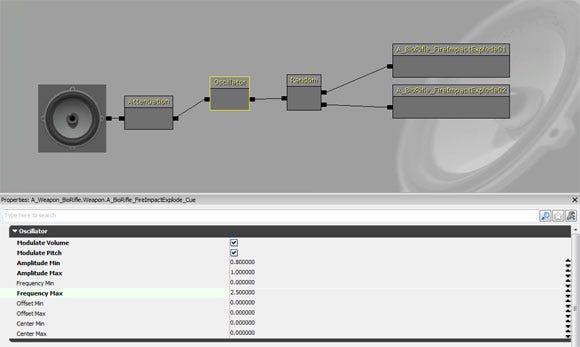

There are a couple different methods used to modulate sounds depending on the engine you are using. Some engines give you means to modulate sounds via their toolset. For example, in Unreal you can build a SoundCue with an oscillator module to change the pitch and/or volume over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1 (click for full size)

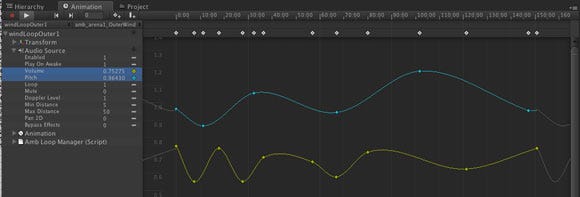

In Unity, you can use an animation component to modulate volume, pitch, pan, low pass filter, or pretty much any other parameter over time (Figure 2).

Figure 2 (click for full size)

While vastly powerful, the drawback of these methods is that the modulation is uniform; therefore it will always be the same every playback. If your engine does not provide a tool to modulate sound or you want more control over modulation, you can create modulation in script.

I have written scripts in C# for Unity to provide for modulation of volume, pitch, and a low pass filter. Doing so gives me far greater control over the modulation control and also allows me to randomize the modulation each cycle or each playback to keep the sound continually evolving.

For the sake of brevity, I have not discussed what other engines offer in terms of modulation and effects, although most can support modulation in some form or another via scripting. In fact, one enterprising developer has written some filters and effects in ActionScript for Flash and posted the source code online.

One thing that is crucial to remember when adding modulation to your sounds is to be subtle in the amount of modulation you add. A little goes a long way and adding too much will draw the player's attention to the changes in sound, which is what you are trying to avoid when creating dynamic evolving sounds from small loops.

Here is an example of a Reactor Core ambience from Free Range Games' forthcoming browser game Freefall, played back in realtime in Unity. The first clip in the movie is just two versions of the sound playing at different pitches in the game world. The second version is the exact same layout using modulation curves on both volume and pitch. As you can hear, the difference is drastic. Furthermore, while you can hear the repetition in the first example, the second example continues to evolve for several minutes before looping. You can watch this movie by clicking here.

A final means which can improve your design while keeping file size down is through stylistic design choices. Based on the type of game your team is developing, the art style or the intended user experience, the sound designer can choose to remove or augment certain video game tropes for the sake of the game's aesthetic and for optimization of the sound footprint. It is essential in all sound design to use your skills to shape the aural atmosphere in a way that makes sense, is unobtrusive and immersive.

However, when trying to create consol-quality audio on a smaller platform it becomes even more important to use your sound design creatively to augment the mood and tone of the game while culling the fat of unnecessary sounds.

Are footsteps really necessary in your dungeon crawler? Will anyone hear that background ambient loop, or is it a better idea to use point source triggered one-shots? If your on-rails space shooter is really all about fun ways to blow up enemies, maybe you should focus on those sounds rather than the player's ship's engines? The way we playback sound and the elements of the game we choose to sonify in the end will inform the final quality of the game's audio.

With a great designer, great sounds, and a solid toolset, amazing sounding games can exist on any platform. Tools available for mobile and web games are exploding with Unity, Flash's forthcoming Molehill 3D API, and even Unreal on iOS and Android.

This is a boon for smaller game developers looking to create console quality experiences in the browser or phone. Through the use of scripting, ingenuity, and aggressively balancing compression quality and sound needs, we can approach parity where one day soon the audio you hear coming out of your browser window or tablet or phone speakers will blow you away (and ideally keep people from pressing the mute button).

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like