Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

On why the phrase "Game audio is 50% of the game experience" is completely false, and why we should be focusing on a common goal.

Originally posted on my personal blog.

There’s been a phrase relating game audio that’s been bugging me for a while now, even though I used to say it myself, and I think it needs to be addressed as its popularity increases. This might ruffle some feathers but:

Game audio is NOT 50% of the experience.

Now, before I get dogpiled hear me out. Let’s first look at the inherent issues with the “Game audio is 50% of the experience” sentiment.

Logistically, if this were true then companies would be dedicating a lot more time, money and manpower to game audio. Hands up if you’ve ever worked on a game that’s received 50% of the budget?* I mean, if literally half of the experience is down to one thing, you’d want to budget for that accordingly.

Similarly, read back that last sentence. The “Game Audio is 50% of the experience” line is equating one discipline’s output to be equal to everything else that goes into making a game. That is a problematic attitude to take and obviously untrue. What is the other 50%? Is it just the art? Then what about all the design that went into how the game should play, the programming to actually make it work? Are they not part of the experience? And how is the game audio percentage broken down too? Often people outside of our discipline will say “Game audio is super important!” when they mean game music, that thing that rekindles the fond memories of playing games without realising what goes into everything else that goes into game audio. Talk to them about audio implementation, especially if they’ve never handled it before, and they’ll morph into some Lovecraftian horror before your eyes trying to understand what you’re on about.

A little like this.

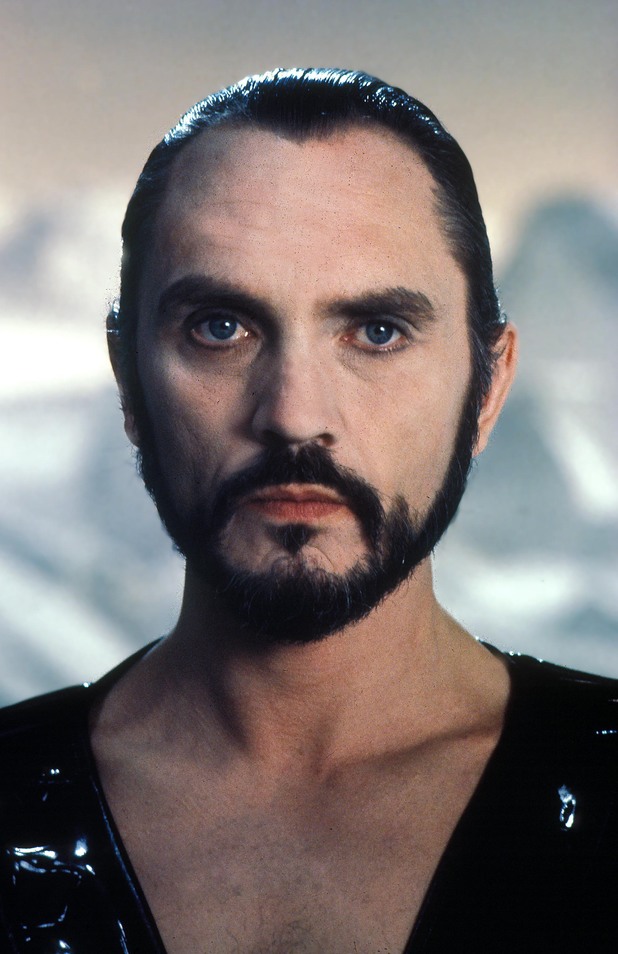

But I understand WHY this statement has become so popular. Game audio types have been at the short end of the stick for a long time, with priorities usually geared elsewhere until the final push towards gold. There’s the sentiment that we’re not important, that we’re the last thing that needs done and the first thing that gets cut, that people don’t “get” us (which is further reinforcing the lonely grumpy audio person stereotype which, if you speak to anybody working in the field, is easily proven false) so they push towards such grand statements in order to compensate. There is a feeling that we should stand up and say “NO! WE ARE THE SONIC MONARCHS OF YOUR EXPERIENTIAL REALM. KNEEL BEFORE NOISE!” in an effort to sway that long ingrained opinion.

...maybe like this.

But we should reshift and refocus towards a greater goal. Because…

The Game is 100% of the experience.

In his book “Game Audio Culture” Rob Bridgett expresses a similar sentiment (in fact, if you’re wanting a more eloquent and detailed read on the matter you should check it out). Games are collaborative efforts that rely on people across the board pulling together to make something excellent. We shouldn’t assign arbitrary percentages or weightings on what makes a game “good”. Everything is important in making a “good” game.

You hear that? We ARE important. Good game audio can help make or break a game. But that is also the case with every other component. There is a sense of frustration that can be traced back to our work and its requirements being misunderstood, if understood at all, by other disciplines. We are this mystical black box that only the Grand Sonic Wizards can enter, with feedback from others usually falling into “Yeah that sounds great!” or “I ‘unno, it just doesn’t sound right” without any additional comments on why. Likewise, our feedback going the other way can be a hindrance too. All of the best intentions go to waste if we don’t have a way to communicate properly, and it is up to everyone on a team to talk to each other, know what they need from you and you need from them.

This lack of a shared vocabulary certainly hinders things, and those of us from an audio production background certainly don’t help things while throwing out descriptors like “muddy” or “airy”, and that’s before we get into anything heavy. Programmers, designers and artists seem to have an easier time in getting information across, and this could be down to an established glossary of terms and understanding that all three have had to work with at some point (some simple art related examples being that designers may need some modelling know-how for level design, programmers for texturing implementation). We’re not at that stage for audio yet, but we’re getting there. Previous limitations have been lifted, middleware is making implementation far easier, audio is being considered across the entire development timeline and brought in from the offset, given room to be tested and influence things rather than a hasty patch up job near the end (most of the time), but these things are only useful to anyone in combination with everything else.

And that swings us back around to the main point. Games are not made by separate entities, carving out their own blocks which are smashed together into a monolith at the end, but by each one working with and influencing each other. This isn’t just down to managing your pipelines and time schedules, but by the human interactions within the team and the ability to share ideas and knowledge that anyone can understand without sifting through pages of Google search results just to explain the basic concepts. To say that “Game audio is 50% of the experience” compartmentalises the discipline even further and detracts from what should be our overall objective: making the best possible game we can across all fronts.

Cheers,

Jaime

*some obvious caveats being one or two man bands, but even at that audio would still not be 50% of the total workload. Even at Team Junkfish, where we are 10 people strong, I’m taking on responsibilities beyond audio, so I’m both a sonic and PR king which gives me two tanks of Zod.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like