Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

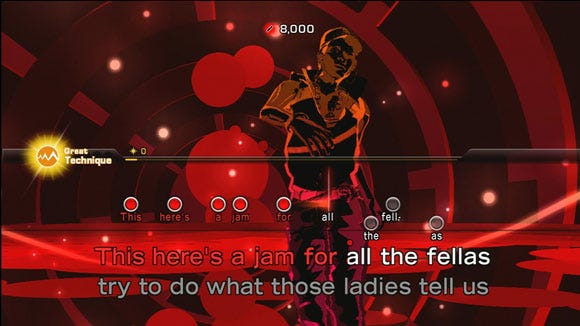

The creators of Elite Beat Agents teaming up with Microsoft to out-Singstar Sony? That's the plan with Inis' Lips, and here, CCO Keiichi Yano explains design philosophy and the drunk people difficulty quandary.

Though best-known, perhaps, for its quirky series of rhythm games on the DS, which includes two titles under the Ouendan series and Elite Beat Agents, boutique music game developer iNiS has been around since 1997.

Founded by a group of musicians, it's one of the only developers that has never produced anything but music titles since its inception -- something the musically-minded Harmonix can't even claim, in fact.

In this in-depth Gamasutra interview, the company's chief creative officer, Keiichi Yano, speaks about the creation of his karaoke game Lips, recently released in North America and out today in Europe.

The creative process behind a music game is unique, and Yano outlines his thinking when embarking on the development of the title, from considering the included peripheral to the balance of game modes included on the disc -- all the way to the core philosophy of wanting to let gamers get closer to their music collections.

How did you get hooked up with Microsoft?

Keiichi Yano: We've had this really long‑standing relationship with Microsoft. I've been working with them ever since I've been doing experiments with interactive music technologies, and working with the DirectX team before Xbox was even Xbox.

We're actually the audio demo for Xbox 1. When they were showing it to developers and press, they would show the audio capabilities of the box, and that was our demo.

Oh, okay.

KY: We've had a really longstanding relationship with them. I've long been saying, "It'd be cool if I could do a game for you guys". One of these times it was actually at TGS, I met up with this guy from Microsoft Game Studios, and I told him, "I really want to do a game for you guys. It'd be cool if I could do a singing game."

He said, "Oh, that's kind of interesting. Why don't you pitch it to us?" [laughs] So, I did, and here we are, two years later...

Well, what sounds really striking is that there are a lot of advanced features in this game compared to a lot of other singing games. It seems like pitch detection is normal, but you also have phoneme detection, and the microphones obviously have LEDs and motion sensitivity. How much of that came from your guys' end? Was it all stuff that you decided, as developers, you wanted to put in?

KY: Oh, yeah, even in my original pitch. I talked about these microphones in the pitch, and I said, "Okay. I'm not even thinking about how much this is going to cost, but this would be kind of be cool if this happened." Everybody laughed at the time.

KY: Oh, yeah, even in my original pitch. I talked about these microphones in the pitch, and I said, "Okay. I'm not even thinking about how much this is going to cost, but this would be kind of be cool if this happened." Everybody laughed at the time.

But, as I went on and thought about the game design more and more, I thought about the party games and all the score mechanisms that I wanted.

Then it just became very obvious to me that this wasn't just some inspirational thing that I had. This is really necessary for this game. I really pushed hard to get all those features in, and now they're here.

Again, these mics are so high quality. We do pitch detection, but we also do rhythm detection as well. It's not just the accuracy of when you're singing the notes, we actually look at what that rhythm is and break that down as well. As you mentioned, [we also have] the phoneme detection and the vibrato detection.

And even with the pitch detection, it's like we have a very fine level of granularity there for if you're really super‑accurate. If I were to get an instrument and play it through these microphones, you'd get 100%, and then you'd score insanely high, actually.

A lot of music games being are made by a lot of different studios, but your studio has concentrated on music games. So, what do you think that you guys are aware of, in terms of music? You have a background in music as well as games, correct?

KY: I, as well as four of our founders, all have music backgrounds. We were all professional musicians at one point or another, and we've been schooled in music. I think that gives us a sense and a depth and breadth of how the music should be visualized how interacting with it is fun.

We've done concerts before, and any musician will tell you, it might be better than sex to do you a live concert, a live performance. To be able to capture what that is, and quantify that into a game experience, that's where the game design expertise comes in.

That chemistry there, to me, is just so powerful. It tells stories. It's a rediscovery of your music, literally. You notice things, nuances in the music, because the game is scoring you. It's telling you these are nuances that are good nuances, and we want you to sing them.

And you're discovering that as you go. That's a powerful connection to your music that you can't really get, and you get really strongly, because it's vocals. Vocals are the most natural thing you can do. Instruments are a secondary thing -- most musicians would say, "Well, I couldn't sing, so I'm playing guitar."

Vocals have all these nuances in there that really allow you to fully capture what any given song is really trying to express. Io be able to play with that, it's just an awesome experience. I think all the companies that do music games [and] that are doing it great, all understand this. We're all able to kind of fuse that experience and compact it into something that everybody can digest.

Something I thought was also interesting was that there's no failure condition in the game. The game will continue. It's more like you accrue more points the better you do. Can you talk about sort of the philosophy behind that?

KY: When you're trying to enjoy the music and you're trying to kind of figure out your connection, your relationship to the song, you don't want it to stop prematurely. One of the things that's great about having original tracks and original videos is you want to see it. You just want to experience it just for that.

Traditionally our games have been really hard. We like to make really hard rhythm games, and a lot of people know this. But, with this game, it's been all about the accessibility. Being able to bring in all kinds of people into this who love their music, right? We want to make sure that we don't want to break that.

That lead me to thinking that, if we're not going to do that, we need something to engage people. Usually, that technique is [to make] them die, or fail, or whatever. But if we can have all these technologies that pick up all these vocal nuances, and create technology that can do that, then we've got multiple dimensions that we could potentially score you.

In addition to the motion sensitivity in the mics, that gives us another dimension that we can give you some more bonuses on. [With] all of that put together, I don't even consider it additive. It becomes this matrix thing. All of a sudden, it's this multidimensional scoring mechanism that we have, which is plenty.

If I really know the song, I can score literally millions of points. I score three or four million points on some of these songs, and that's great for the person that is very confident in his vocal capabilities. But, for the person who might not be, or if you're just drunk, it's just like you don't even care.

But you just want to jam to the song, and you're [warbles incoherently], and it's all this crazy stuff. But, you're still getting a score, right? And that's really important, because at the end of the song, you're drunk and you're still saying, "Ha! I scored better than you!" or whatever, right?

And that is really enough to carry the experience. People don't even question it. [They don't say], "Oh, yeah! It's not ending prematurely." I would even say that a lot of people that don't normally play games even think about that. If anything, it's the reverse. "Why did the song end prematurely? I want to enjoy the song." That's what we're giving them.

When you were deciding what factors you wanted to try -- when you were sitting down initially to design the game, and thinking about what factors you wanted to track in terms of the performance, and how you wanted to design the game in terms of players not being able to fail it -- how did that process work for you? Because it's sort of different than designing levels or something like that. Did you sit down and just start writing documents, or did you start sort of prototyping it out?

KY: We really take a kind of multi‑tiered approach when we design games. I knew from the get‑go that I wanted to make a game that you wouldn't fail. And I knew that I'm very familiar with a lot of music technologies, so I knew that we could use this to perhaps extrapolate this from the vocals, and then we just started building those technologies, testing them out in the game.

As we moved forward in the prototyping phases, you realize more things. "Oh, what if I combine this and this. That would be awesome. And we can score them again on that, and give them bonuses, or whatnot."

It was, at first, a vision of, "We want to pick up all the nuances of the vocals and try to make sure that a breadth of players, from drunk to awesome, could basically add a little bit of spice into it, and get a score." That was the whole point. Because, traditionally, in music games, it's all been about, "I followed exactly what you told me to do," and that was it.

But, we're allowing you to do extra things of a broader detection level. It's a bonus. You don't have to do it. But, if you do it, it adds more points.

That's something I've been curious about. Very few music games have had any capacity to deal with improvisation, or going off of the primary rhythm. There have been some examples of that, but it's something that's very important to musicians, obviously. Is there a drive to see something like that come to music games?

KY: Oh, yeah. We're in a day right now where it's about how the user can express himself through this game, right? So, with our game, we already provide a couple of things. We provide the ability to use your own music. We provide all this picking up of vocal nuances. There are just a whole bunch of things that we provide already.

When you combine those things, it starts to become really personal. It's just a really personal reflection. I'm a student of jazz. What is jazz all about? It's about improvisation, right? And how much you can make the music cooler.

As we move forward -- and we're kind of evolving this genre -- I think we're going to see a lot more of that happening and awesome ways to figure out that we can do that as an added bonus.

I think there's just a great thing about not punishing people, giving people bonus points. And then, you go online and you're competing for, "I know this song better than you." Or "I can spice up this song better than you."

With music games, we're just trying to create a very positive experience. We want to try to stay positive for it. That's really important, and I think we will see more of that as we move forward.

As you know and I know, karaoke technology in Japan is very advanced compared to some other markets. Did you look at any of the features that were on karaoke machines that are available in Japan? Just in terms of just having used them, or did you do research or anything like that?

KY: Well, I live in the country, and that's something we do all the time. Without even really researching it, we know and understand that a lot of these things are happening. To be honest, it's probably somewhere in my head, but I didn't really look to that that much because I knew I wanted to create an experience specially tailored for the home.

That might not be this one‑off thing. Because you're going to buy this, and you're going to grow with the game. You're going to advance with it, you're going to grow with it, you're going to evolve with it, yourself. I wanted to make sure this game would have all the mechanics that would set us up to enable players to do that.

So, what's interesting to me is the mini‑games. They certainly feel a little more like iNiS.

KY: [laughter]

Was that part of the initial design, to have those mini‑games, and how did you arrive at them, and what do you think they bring into it?

KY: Yeah, it was definitely part of the design to have different backgrounds that the user could select, not just the video. I think, our background, with the other music games that we've done in the past, we just like to have a zany experience, right? [laughs] We're all about having a lot of fun in crazy ways.

I really wanted to make sure that we got that sense, and that fans of our previous games could look at that, as you noted, and say, "Oh, yeah, that's that little bit of iNiS in there." Not to mention, "I can score millions of points." [laughs]

It came very natural for us to say we want to put these games in, and let's have a little bit of a wacky presentation in them, and just have fun with it.

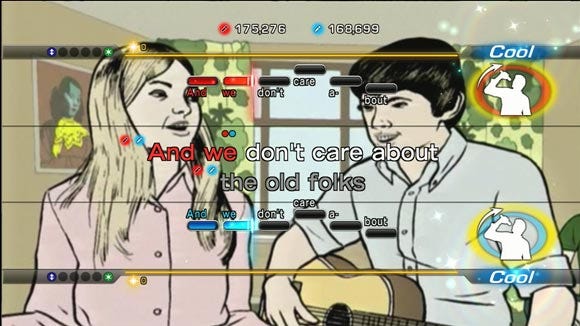

The mini‑games also seem like some of them are a little bit more skill‑based and some of them are more obviously catered to appealing to a casual audience. I'm assuming this is a natural outgrowth of the different audiences you saw in the game, and that's kind of the way the game goes, is that you're trying to appeal to the broadest audience of everyone from hardcore to casual gamers, right?

KY: When we designed the games, I didn't really think about the difficulty level. I just wanted to make sure that we had some type of a competitive mode, some type of a cooperative mode, and some type of a mode where maybe you are pressured into doing the right thing so that you can see the song to the end.

That's really how I approached it. [I just tried] to make sure that we had things that were appropriate for each type of singing. That's how we came about it.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like