Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"Call of Duty: WWII used original recordings of historically-accurate weaponry and vehicles, so we wanted to make sure the sound design would be unobstructed by musical elements."

You may not recognize the name Wilbert Roget, but you've probably heard his work. Roget was a music editor at Lucasarts for many years, and he wrote original music for Star Wars: The Old Republic and Star Wars: First Assault, and arranged and supervised music for Monkey Island 2: Special Edition. Since then, he's been the composer for titles like Guild Wars 2: Path of Fire, Lara Croft and the Temple of Osiris, and Dead Island 2.

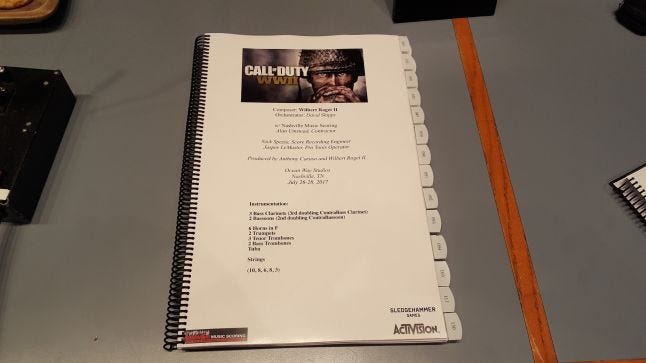

Roget also served as composer on the powerful, memorable music for the recently released Call of Duty: World War II. He spoke to Gamasutra about his inspirations, his attempts to stay true to the time period of the game, and how to score with special f/x in mind.

Roget: I had played and loved Sledgehammer Games’ previous game, Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare, and was strongly interested in working with the company on a future project. One of my former-coworkers from LucasArts had worked as a sound designer on Modern Warfare 3, so I asked him to put me in touch with Sledgehammer Games’ audio director, Dave Swenson. It turns out Dave had recently played a previous game I scored, Lara Croft and the Temple of Osiris, and so we met a few weeks later at the Game Developers Conference. Several months of follow-up meetings and Skype conversations later, and eventually I was hired.

Composer Wilbert Roget

"All in all, it was about six months to write the full score."

We had our first on-site meeting to begin the process sometime in late January. But I started sketching various ideas on paper all the way back in August, as soon as I knew it would be a WWII-era score. The score for the original Call of Duty had such a big influence on me back in college, so I immediately had some ideas I wanted to explore.

Ultimately very little of those sketches made it into the game, with the exception of the minimalist triple-meter concept I used in the 'Berga' track. My first game-specific pieces were written in early February, and we had our final recording sessions towards the end of July, so, all in all, it was about six months to write the full score.

"A Brotherhood of Heroes" by Wilbert Roget

For my overall direction, my inspirations came from several different media. I was already familiar with the first Call of Duty scores as well as Modern Warfare and Advanced Warfare, but when the project began I started to study a few war films to see how their scores interacted with the drama.

Of those, I’d say The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, and Saving Private Ryan were the most tonally relevant even though my score doesn’t sound overtly similar. I also studied several pieces of 20th-century art music very closely: Claude Vivier’s 'Zipangu,' Toru Takemitsu’s 'Requiem for String Orchestra' and of course Penderecki’s famous 'Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima.'

"I only had an illustrated storyline document to work with at my personal studio. I didn’t have a chance to play the game while scoring."

After my first meeting onsite at Sledgehammer Games, I only had an illustrated storyline document to work with at my personal studio. Sledgehammer sent me a few gameplay capture videos later on, but I didn’t have a chance to play the game while scoring. Actually, when writing the first few in-game pieces, I used gameplay footage from Call of Duty 2's 'Rangers Lead the Way' level to check if my own music would fit the mood and soundscape, as that level is both high-octane and has long stretches without music.

Testing against gameplay footage reassured me of the efficacy of my sonic experiments, like my use of solo strings and period-accurate musique concrète. It also helped me arrange the music in such a way that it complemented the sound design instead of competing against it. And then towards the end of the project, there were two pieces, 'Birds of Prey' and 'Berga,' which I wrote for specific levels' gameplay footage.

"The game used original recordings of historically-accurate weaponry and vehicles, and so we wanted to make sure the sound design would be unobstructed by musical elements."

This was one of the first considerations I had when developing the musical direction for the game, and one of our audio director Dave Swenson’s primary concerns when starting the project. Call of Duty: WWII used original recordings of historically-accurate weaponry and vehicles, and so we wanted to make sure the sound design would be unobstructed by musical elements.

We had several solutions for making sure the music would be effective while avoiding conflict with the soundscape. First off, I stripped down the traditional battery of orchestral percussion, avoiding sounds like snare drums and mallets that would compete with gunfire or stick out of the mix. I also avoided big epic trailer-esque percussion and overt use of synthesizers, since I envisaged the soundscape would provide more than enough punch and excitement in the mix.

I did use some large drums and dhol ensembles, but I never let their volume get above a mp level; their only purpose was to add bass and a tiny bit of motion to certain high-intensity action pieces. In place of this percussion, I employed the aforementioned musique concrète technique: sounds from period vehicles and other military sources were heavily processed and used to create a "haze of war" effect.

I avoided high woodwinds as well, and I only used trumpets to double the horn section at key moments. The strings were a fairly typical section with 34 players, but I intentionally avoided the highest range of violins to avoid letting the orchestra poke out too much. I also used solo strings and string quartet extensively, to get sharp and crisp rhythmic elements in action cues especially.

Lastly, we embraced a relatively dry overall music mix, with lots of high-end clarity and not too much reverb. As a result of all this, the music was mixed somewhat louder in-game than is usual for the franchise, but it still never conflicts with sound design.

"Welcome To The Bloody First" by Wilbert Roget

For Call of Duty: WWII, the music team at Sony Interactive Entertainment was hired to supervise, mix, edit and implement the score. They would spot the game levels and assign me music "suites" that they could then edit and implement into the game, with music changes at key moments during each level. As a composer, I didn’t need to keep the gameplay dynamics in mind while writing -- I simply had to make sure that each piece I delivered contained a few different moods, had stinger moments built-in naturally, and featured as much movement and development as possible.

We did have a stealth music mechanic however, which involved writing pieces that included brief one-shot stingers for when the player is detected by enemies, as well as a few swells into combat. That was the only case where I had to write to the implementation. Normally I would write through-composed pieces with enough drama for the Sony team to edit from.

"For Sledghammer's team to do their work, I needed to deliver my music in up to 30+ stems per cue."

For their team to do their work, I needed to deliver my music in up to 30+ stems per cue. In other words, instead of just sending over a stereo render of the piece, I had to split into "low strings short," low strings sustains," "high strings short," and so on for the entire orchestra -- as well as delivering individual renders of every non-orchestral element.

My solution involved creating a folder within my Reaper project file that contained in-line renders of all the stems, with automatic soloing via track groups. I’d still have to manually record each stem, but this made it very easy to test my stems for accuracy. In the rare instances where I needed to revise a cue even after it was approved, those changes were easy to make.

Finally, I wrote the entire score in a single Reaper project file, but I wouldn’t call that a technical "challenge" per se. This is how I have written every one of my orchestral scores since Lara Croft and the Temple of Osiris, and because I only use a single PC without VEpro, this saves me tons of time starting new cues and revising old ones. It also helps me keep a consistent mix, and it helps me easily reuse live-recorded solos and sound design elements.

One unique aspect of working with the Sony team in producing a score is that they don’t have a big generic cue list saying, for instance, “Ambient 08” or “Action 13”. Instead, they assign specific suites with clear direction on the mood and sonic direction. So as soon as I had an idea and was sketching on paper, I already had a good sense of the emotional context of the piece, and how I would satisfy it.

From there it was just a matter of arranging everything, creating a synthesized mockup, and frequently taking a step back to see if there were other elements I could add (or remove!) to help the piece fit the overall musical direction. For instance, my final step in most tracks would be to create a second layer in the music, which again I called the "haze of war" effect -- this usually meant adding things like brass-sliding electric guitar played with an ebow and tons of reverb/delay, or adding my musique concrète elements like steam train sounds, distant explosion debris, and various metallic sounds.

Because Call of Duty: WWII takes place in real-life settings, it was crucially important the music was respectful in tone. For the score to work, I needed to make sure that every piece had a concise focus, avoiding excessive embellishment in the orchestration and especially melodies. At the advice of our audio director, I used as few "syllables" as possible in my themes and motives, and to make sure that every piece in the score sounds unique to this game, I used signature sounds and themes as much as possible. For that reason, I believe this is the most cohesive score I've written to date.

"Game music is an incredibly competitive field, but having technical knowledge as well as creative ability will certainly give you an edge."

I’m in this industry because I'm in love with games and the way they are created. We have brilliant artists, programmers, and designers who are constantly pushing the envelope with clever solutions to both creative and technical problems. When I play a game, that's what I’m looking for: titles that create memorable, fantastic and seemingly impossible real-time experiences. Many of my friends are in the games industry working as those very same artists and programmers, and I enjoy reading and studying the technical side of games creation almost as much as I enjoy playing them.

My advice to other composers looking to enter the games industry is to know the medium, do your research and play both recent and classic titles. Understand how games scoring is different from film and TV, even when it's the same composers working on all three. I’d also recommend studying how game audio implementation works, and practice by deconstructing how a game’s sound design and music implementation work while playing the game. Game music is an incredibly competitive field, but having technical knowledge as well as creative ability will certainly give you an edge.

You May Also Like