Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

This audio feature has Shaba's Meyer explaining how sound concepting plays a vital role in a game's creative direction, with real-life examples from Spider Man: Web of Shadows.

[This audio feature has Shaba's Meyer explaining how sound concepting plays a vital role in a game's creative direction, with real-life examples from Spider Man: Web of Shadows.]

Concept art is a tried-and-true means of developing the visual look and feel for a game in preproduction. Techniques like sketches, character studies, and visual brainstorming generate early ideas as to how various game assets should look in the final product. Artists use these concepts as a foundation to build the game world, so this early visual design plays a key role in the development of the game's overall style and feel throughout production.

In much the same way, sound concepts can -- and should -- play a vital role in game development. Though not as widely-considered or visible, sound concepting can be used to solidify an audio direction, create sound palettes, prototype various effects and ideas, define the audio characteristics of the game state, develop an understanding of the importance of audio to a project, and even help sell the game to a publisher.

Sound concepting consists of many exercises, both creative and functional -- but for this discussion, "sound concepting" refers to the construction of sounds used as a basis to derive sonic ideas for a project. Sound concepts are not just mockups, but a serious study into how the aspects of the world should sound in the game.

These concepts may be a series of ideas for a single sound, a short soundscape, or a complex sound synced to an animatic -- basically, anything which can be used as future reference for the sound designer's vision. Sound concepts are just that: concepts, not final assets. However, studies developed during the concept phase often evolve in some form into finished sounds.

Concepting entails various exercises, experiments, and studies used to create a framework from which a game's audio can develop. It affords the audio team the opportunity to find the game's voice creatively, and begin to work out any technical issues to ensure the team's vision and ideas are possible and iterated upon. In practice, sound concepting is the act of mixing the "designer" side of the sound designer with the "sound" aspect.

The point of sound concepting is to experiment freely, and test concepts against other to help them evolve. The designer should create without constraints, until he or she finds what works best sonically, and then figure out how to make these ideas work within the game engine.

Before exploring some examples of sound concepting and demonstrating how it can help a project, I cannot stress enough the value of integrating the process of concepting into pre- and early production work. The pre-production phase is invaluable to a project, in that it is often the only time in which designers have the time to experiment with various methodologies and content freely. The goal of concepting is to develop innovative ideas which can translate into final content through experimentation and iteration.

For an audio team, concepts aid in building a concrete audio design early in the project. By engaging in pre-production experiments and exercises, designers begin to think about various aspects of the game while the rest of the team is also engaging in the same practice. Most collaborative design choices occur during this phase, when ideas can be conceived, prototyped, and scheduled. Pre-production time is invaluable for generating long-term project goals and deriving multiple solutions to ensure their implementation.

Creating these initial concepts without boundaries often allows designers to be more productive in generating unique, creative sounds. By giving full creative reign first, and then re-constructing sound design under the guise of an audio engine, concept work helps audio designers think more clearly about how they'll tackle obstacles and limitations within a game engine -- while still having the freedom to experiment with limitless solutions.

It can also help mitigate the number of placeholder sounds that trickle into the game, by giving the designers time early in production to solidify the nature of important sounds in the game. (For more on the importance of audio in early project development, see Rob Bridgett's article, Designing a Next-Gen Game for Sound).

Most sound designers already engage in sound concept work on some level, but it is important to ensure that time is set aside to give a designer the chance to develop and explore various sound concepts before running into full blown production. Once sound concepting becomes an integrated part of a production pipeline, the results are higher-quality sound, greater innovation, and better polish.

There's also better cohesion across the multiple disciplines of video game development in defining a shared vision. Now, let's examine some practical uses of sound concepting in both hypothetical and real-world game development situations.

For our first exercise, let's say we have a new game that will take place in an alien jungle. The first part of any concepting work is to ask a lot of questions:

What is the jungle going to look like?

Will it be quiet, or noisy, or creepy?

Is it teeming with strange life?

If so, is this strange life hostile or friendly?

Is it insect, bird, plant, or some other life form-based?

Does it respond and react differently when the main character performs certain actions?

Based on direction from design documents, lead designers, or a sound designer's own ideas, he or she may create varied yet applicable versions of this alien world's soundscape. The designer then compares these ideas, by playing them against each other and evaluating what gels with the game's visual and gameplay design.

These concepts can also aid in determining how to tackle various components of the audio design. For example, what does that strange jungle life sound like in the morning, afternoon, evening, night, or any other state changes the game may have?

Each of these questions can be weighed against each other by creating numerous concepts to explore these variations and the means to transition between them. By playing with these concepts, the designer can begin to shape how he or she will design the final sounds and trigger these changes in the game engine.

The most memorable characters are often defined within a game by their sound palette. A character's sounds help project the illusion of whether he, she, or it, is fast, strong, magical, eerie, or something else entirely.

Audio concept work can greatly aid designers in constructing a palette of sounds appropriate for various elements and themes within the game, including character design. By experimenting with various possibilities for sounds, a designer can begin to create useful groups of sound components which can then be used as building blocks for sound design within the game.

In my most recent project, Spider-Man: Web of Shadows, the city of New York becomes infected by a strange symbiote goo, which we call ichor. This ichor turns the citizens of New York into vicious monsters, who in turn spawn more ichor and create more hideous monsters.

The ichor itself was a very important thematic set of sounds to get right, so I chose it for sound concepting work. Early in development, I was given a concept animation of what the ichor may look like, and from it I constructed a palette of various sounds which would give these various forms of the alien life. These sounds were created after watching the movie numerous times and talking to various artists and designers about their intentions for the ichor.

Figure 1: Ichor sound concept

I engaged in field recordings and foley work to capture various appropriately slimy, gloppy, and gooey materials. Since the ichor was also "alive" I wanted to inject some subtle vocalizations into the movement as well, and did so with various human vocalizations, as well as some pig squeals, cat growls, and my brother's dog, Ke-K'oa.

I then "scored" the concept animation with a mix of how I envisioned the ichor would sound in game (see figure 1). This was a very early concept in production, and now it is amusing to compare this concept to what we have in the finished product. The creatures in the game do not sound or look at all like this movie, but the concepting provided a realm for experimentation, helped solidify the design of the ichor, and also created a library of sounds I could pull from when designing our various symbiote-infected enemies.

Prototyping is another area where sound concepts are helpful as design tools. One area we completely ripped out and overhauled in Spider-Man: Web of Shadows was combat.

Early concepts looked into the use of slow-motion to emphasize Spider-Man's super abilities, provide easier transitions between air, ground, and wall combat, and make combat in general more dramatic. Slow motion would be used similarly to bullet time in other games, giving the combat a more dramatic feel by bringing the high action to a manageable pace.

I created a sound concept for slow-motion combat to demonstrate ways which audio would help make combat more dramatic as well. The benefit here was that even though our combat system would be completely redesigned, we had an existing engine and an existing game we could use to demonstrate the sonic enhancements we had in mind.

For this concept, rather than create a completely new audioscape, I had one of our designers capture some combat from Spider-Man 3. I took this footage, and added some sweeteners and effects over it to help convey our ideas for how slow motion combat would affect the game's sound. I then made a movie which played the two versions back to back to give people a more overt sense of how our game would differ (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Combat audio sound concept

My main alterations were the use of a pre-attack "wind-up" sound for combat attacks while in slow-motion, some pitch shifting, a specialized reverb, and a short delay with a moderate feedback tail on the impacts.

While the sound and visuals were never meant to convey how combat would actually be in Web of Shadows, the concept effectively demonstrated to the team some of our ideas as to how we would design and integrate audio into the new combat system once it came online and the Spider-Man 3 combat was completely removed from the game many months later.

While the team was very happy with the slow motion concept and excited to implement it into the game, once we began working on our combat scheme, we found that the constant extreme time dilation actually took away from the game's pacing, so we opted for a much quicker and more subtle slow down, which in turn negated this concept.

Slowing down the gameplay and adding a delay to the mix bus no longer provided the dramatic impact it was initially intended for, and in fact using these elements as often and quickly as time dilation occurred made the entire mix sound muddy and confusing.

However, design elements that were created as a result of these experiments made their way into some of Spider-Man's combat effects. Like any concept work, sound concepts are not cast-in-stone directives, but are subject to change or to be nullified based on internal or external factors. Yet the very act of concepting helped create interesting ideas which we were able to use in ways other than initially intended.

Sound concept work can also aid in defining and refining the general mood or tone of a game. Using another example from Spider-Man: Web of Shadows, the city of New York itself is transformed over the course of the game from the bastion of metropolitan life into a war-torn, apocalyptic hell.

I chose to chronicle this change via sound concepting, as I felt it would help me develop the varied ambiences for the game and also give the rest of the team an idea of the overall direction. As with other concepting work the first thing to do is ask lots and lots of questions:

What's our neighborhood like? (rich and quiet, country setting, suburban, frozen tundra, etc.) In our example, it's Manhattan: busy, bustling metropolis.

What is the nature of this apocalypse? (nuclear weapons, war, alien invasion, etc.) We've got a good ol' alien invasion here, but the invasion itself is a slow subtle process, not a War of the Worlds type of attack.

How does the sound of our initial state compare to the end state, and what is the sound of one becoming the other? Manhattan transforms into an alien apocalypse...

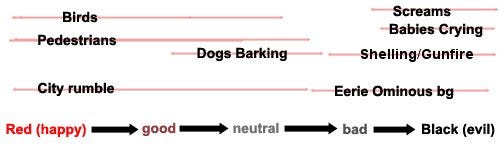

When setting the mood across game states, one method I employ is to create a simple chart detailing the key characteristic sounds of each stage of the game, how they blend, and when new types of sounds are introduced (see figure 3). This creates a map which can then be used to design sound components, play them against each other, tweak their parameters, and add new elements. Through experimentation, the sound for each game segment is developed and manipulated to transition between these various states.

Figure 3: The sound chart

Once I created this map, and checked out the concept art we had for the various stages in the game, I began compiling and designing some of the elements I had sketched out in my chart. To fully convey the transformation of the city from "normal" to "infected," I took the art I had received and made a movie crossfading between the various states of the city, which I then scored with my audio concepts (see figure 4).

Figure 4: The environmental change sound concept movie

This concept not only gave me a sense of how the audio tone might change throughout the game, but it also provided the rest of the team with an idea of how the game's design and visuals would be reflected through the audio. This transformation from what we expect in a Spider-Man game to something completely unique and foreign was very important to the game, and very important for the team to understand early.

Using my sound concept, which in turn used early visual concepts, we were able to give the team an idea of just where this game was heading. These exercises played an important role in energizing the team about the project and keeping them informed and excited about our direction.

This is perhaps one of the most interesting effects and benefits of sound concept work: the impact it has on other members of the team. So much of pre-production content is visual only, and adding the extra dimension of audio to pre-production concepts can provide the team with a unified vision of the game's direction and design during the early stages of development. The result is that the team better understands the game's direction early, and gets more enthusiastic about the project in the process.

A secondary result is that the team also becomes more interested in the sound of their game. On Web of Shadows, once we began creating and sharing our sound concepts, I noticed a dramatic increase in interest in regards to sound. I was approached by numerous artists and designers with requests to create more sound concepts.

Ostensibly, they wanted their ideas to seem more polished by adding sound, but these concepts each contributed in some way to the game's audio design by giving me the opportunity to focus on developing and shaping what would become many of the important elements within the game.

Sound concepts also help sell a project via increased dramatic impact when presenting early concepts to a publisher, company executives, marketing departments, etc. Whether an independent developer or a studio owned by a publisher, nearly every team has to pitch their ideas to a publisher. Audio is the "magic," forgotten element often neglected in pre-production planning and development.

Sound concepts can open up a whole new realm of ways to show off a project's progress, especially in the early stages of development. It shows these other entities that the team is fleshing out every aspect of the game design-- from art to animation to gameplay to sound, and adds polish to pre-existing assets. Sound concept work can assist a team's long term goals by helping set a direction for game components, generating work which will extend into the final product, and selling these ideas to the folks with the money.

In our early milestone deliveries, the sound concept work played an important role in explaining to the executives at Activision where our game was heading. The sound concept provided a new layer of cohesion to the overall design of our ideas, and made that understanding a more complete sensory experience.

In summary, sound concepting ensures that the audio team is more involved with the project, while at the same time involving the project more with the audio team. Employing early conceptual work on the audio front is an invaluable means to help all team members understand the importance of audio in the final product.

Sound concepts help foster communication, experimentation, and a greater assurance for unique, quality audio by taking the time to invest in a teams' vision in more than just the visual sense. The benefits are immeasurable. The importance of engaging the audio team early in pre-production to give them the time to experiment and conceive of the best possible audio design for the game is essential.

Sound concepts are often a luxury, in which designers participate only when they have a little time between projects or just as they get pulled on to a new project. This practice must change. I implore all audio directors, producers, and project leads to begin budgeting time in your pre- and early production schedules for sound concepting. Sound concept work helps fuel greater creative development across disciplines in any game and helps to ensure overall success.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like