Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Richard Jacques is a musical icon to Sega die-hards, thanks to his work on titles like Sonic R - and in a wide-ranging chat, the composer (The Club, Mass Effect) discusses the state of game music in 2008.

Richard Jacques is a legendary name among Sega die-hards, thanks to his music composition work during his time at Sega Europe on games such as Sonic R and Metropolis Street Racer - as well as assists on other classic Sega titles such as Jet Set Radio.

But, having left Sega for a freelance career, his compositional credits extend to the current day, with projects like The Club, additional work on Mass Effect and Sega Superstars Tennis on his resume -- a blend of the old and new, even in 2008.

Here, in a wide-ranging interview, Jacques talks about his feelings on how iconic music may be making a comeback in games, the importance of dynamic soundtracks, the concept of a composer-led game design, and even spills the beans on classic Sega projects that fans have debated the merits of for years.

So what have you been doing most recently?

Richard Jacques: Last year was an incredibly busy year. I was working on Mass Effect -- focusing on that -- I was working on The Club and Conflict: Denied Ops... Also, I've been working on Sega Superstars Tennis, which is going to be great for the fans, I think. They've done a really good job on that. And I'm currently working on Highlander, which I have another three or four weeks to finish.

With the Sega game, is that kind of back to form?

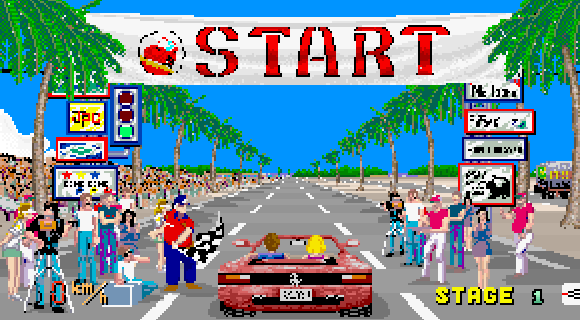

RJ: Oh yes. I'm a big Sega fan. I spent eight years of my career working with them, and I love their games and their look and feel and stuff. This particular game, using all their huge characters and IPs and putting them all together with the Virtua Tennis 3 engine, which the guys at Sumo Digital over the UK put together...it's just a great celebration, really, of all things Sega.

I was asked to write a whole bunch of custom music for the frontend and the main theme and the trailer, and I've been remixing Space Harrier and Virtua Cop and things like that. We've also done... 85 of the original tracks have been upmixed to 5.1 surround. So they've gone all-out on that, and it's going to be a lot of fun, I think.

It seems to me that over time, music has gotten much less iconic and more like background-y, or representational. It's like sweeping orchestral stuff, and not like real iconic music. Why do you think that happened?

RJ: It's a good question. I think partly, it's because of the way games have changed. If you were playing, ten or fifteen years ago, a Sonic or a Mario or a Metroid or something like that, it would be very clearly level-based or goal-based, and there would be a piece of music for that zone or that level.

RJ: It's a good question. I think partly, it's because of the way games have changed. If you were playing, ten or fifteen years ago, a Sonic or a Mario or a Metroid or something like that, it would be very clearly level-based or goal-based, and there would be a piece of music for that zone or that level.

Consequently, the gameplay challenges would warrant you playing that level quite a few times before completing it and progressing.

Now, games are structured quite a bit differently, and the atmospheric and orchestral thing is just as valid now, because the gameplay is so different.

If you're on a huge, 30 to 40 hour playing game like Gears of War or Halo or Mass Effect or something like that, you can't be bombarded with music. It has to be there to back up story and characterization.

I think back in the day, with the Sonics and Marios, music played a different function, whereas today, it's to support characters and narrative, to create emotional rises and falls in the stories and arcs, etcetera.

I think we have gone through a certain..."renaissance" is the wrong word, but I think the whole orchestral thing has now peaked, because everyone wanted to do it, and they've done it, and blah blah blah. And now they're finding, "Right. We could go that route, or we could go a world-ethnic music route, or we could go a computer-electronica route."

So I think now, it's finding its place as a valid tool and a valid stylistic point of reference for game designers, producers, and composers alike. But it's not necessarily the be-all and end-all of it. I mean, I love composing in that genre, because that's what I was trained to do -- I was classically trained, etcetera -- but you could easily do a score with a completely different approach, which would make just as good a game score.

I can remember the theme songs of those older games, and part of it is, as you said, probably because I had to play through the levels so many times.

RJ: Yeah, the exposure...

But still, it's somewhat disturbing to me that I can't call to mind the music of recent games, a lot of them. Exceptions are like Halo, but that's partially because you have to wait on that loading screen for such a long time.

RJ: Sure. And that has a big, recognizable theme in it, and it was probably deliberately composed that way, whereas I couldn't sing any music from Gears of War, because it's dark and perfect for the game, in my opinion.

There has to be a conscious choice, I think, a lot of the time, between game designer, lead designer, and composer, about "How can we attack this? Are we going to have the player keying into this one musical idea or collection of ideas, or is it just going to be a low underscore supporting what the gameplay is doing?"

On Highlander, I'm taking the approach where I have a really huge main theme, which you do get snippets of throughout, and you're rewarded at the end with the whole song in its entire glory and blah blah blah. That's been very carefully thought about and deliberately done that way, like Headhunter.

When I did that, I had three very strong themes that are played throughout the levels, etcetera. It depends on how the composer wants to approach it. Underscore and things that you won't be able to sing back has just as valid a place as big, thematic, melodic kinds of songs, and those kinds of things as well.

Eidos/WideScreen Games' Highlander

Do you think there will be a time when we can get back to more iconic music?

RJ: I think we're starting to see that already, to be honest, in a small way. What we're seeing now is... I grew up with very old Sega consoles and arcades and Spectrums and Commodores and stuff, and I think now, as a generation, we're maturing. A lot of my friends have got kids of their own.

What we're seeing with things like the Wii and Xbox Live is that we're seeing this kind of resurgence of... let's call it "old school," for the moment. A lot of this kind of stuff, which is going back to the real root of video gaming. I think in terms of music, that is already starting to happen.

It's a two-tier system, really. You've got the Call of Dutys and stuff up here, with their massive, sweeping, orchestral scores, but then you've got stuff like... look at the latest Mario. They're doing amazing... I would still call that iconic music, on Galaxy, and that type of thing, and Super Stars Tennis, I've been going back to that traditional, iconic video game music as a genre, if you like.

Just as an aside, do you find it difficult to compose a distinctive theme for Highlander when you're following Queen [who composed the original film soundtrack]?

RJ: Uh... (laughter) Not really. I can't talk about it too much, since we're releasing in a few months' time, but no.

We've taken a different approach that's right to the game, to be honest. And you wouldn't even try to go anywhere near that music, because it's so awesome.

How have you found the process to have changed over the years? You've been doing this for a really long time, longer than most have been doing it consistently.

RJ: In terms of actually creating the music, or...?

Both in terms of the creation of the music and the tools available to you, but also in terms of the designer-composer interaction, and what they want from you and these sorts of things. It's a very huge question, sorry.

RJ: Sure. Well, no, it's a great one that needs covering. When I started my career, we were working on very limited technology. The first game I shipped was on the 32X, which had no...

Which one was it?

RJ: Darxide, which is a 3D asteroids game made by David Braben of Frontier Developments. And then Shinobi X, which I did the European version. That was on the Saturn. I wasn't allowed to use the CD-ROM for any music on that.

RJ: Darxide, which is a 3D asteroids game made by David Braben of Frontier Developments. And then Shinobi X, which I did the European version. That was on the Saturn. I wasn't allowed to use the CD-ROM for any music on that.

The technical challenges were pretty tough in those days, but creatively speaking, I would say that I was given more free reign then than I am now. I think it should be the other way around.

I'm sure composers who have only been in the industry for a number of years or just recently will say, "Oh yeah, we get all this freedom," but back in the day, I was literally given a game and pretty much did my first instinct -- composed on my first instinct, whereas now, it kind of tends to be about comparison.

"Oh, we want it a little bit like Hans Zimmer, with a little bit of this and a bit of that." Well, that's fine, and I'll take that on board, but I'll still interpret the game in my way. The game is what speaks to me, not a bunch of CD references that someone's put together, because that's just referencing something else, and I don't understand why people do it all the time.

I always say to a developer or a lead designer or whatever, "I want my score to sound like your game. Even if we haven't worked out a brief, I want my music to sound like your game, not this film or TV series or this other game."

I think that's stifling the creativity of the composer greatly. It's fair enough giving guidelines like, "We want electronica or orchestral," or this, that, and the other, but I always want to put my own identity to the game, because it helps identify the game in its own right.

Yeah. People are constantly using reference points for games and game design, I think. I think it's symptomatic of a slight lack of creativity, sometimes.

RJ: I would agree, yeah.

It's unfortunate, but it's good that at least you can get some of your own self in there. Have you had to work with games that had existing scores? I guess there's the Sega one that's happening now, where you're doing remixes and stuff, but I'm thinking more like... our audio columnist works at LucasArts, so he's got...

RJ: Does it fit the mold? I see what you're saying, yeah.

Have you found that you had to do that sometimes?

RJ: The only time I've really had to do that is working on licensed IP. Starship Troopers and Highlander are obviously existing IPs which had a number of film or TV releases or whatever it may be, so it has to sound like that. And both of those have quite iconic styles.

Starship Troopers was always a tongue-in-cheek, bombastic, over-the-top score, and that's exactly what I did for the game, because that was right for the game. I didn't use anything. I did it purely originally.

But I did it bombastic and over-the-top and slightly tongue-in-cheek. And that fitted the bill, because at the end of the day, it's a licensed IP for Columbia Tri-Star Pictures, and they're not going to approve it if it doesn't fit in with the whole mold. And the same goes for Highlander, as well.

But on other things, even in series... maybe Jet Set Radio, a little bit. That style was established from the first game. I worked on one track, and a lot of the tracks were done by Hideki Naganuma from Sega Japan, and we had other artists.

That was just a great collaborative process. I think everybody was on the same page just by looking at screenshots of all the cel-shading and the rollerblading and tagging and stuff.

It was so obvious what it needed, but we still gave it a slightly poppy, fun edge to it as well. There's no point in having NWA or Public Enemy in that kind of game. It wouldn't have worked. So for the sequel of that, we'd already established the style. We just grew on that, and made it more contemporary and etcetera.

So if you're working on a big, long-running series... even like Sonic, when I did my first Sonic game, which is Sonic 3D Blast, on the Saturn and PC, I was taking my main reference from the Japanese version of Sonic CD, because in my opinion, it's an absolutely brilliant score and brilliant game music. I thought that was the excellent blueprint for Sonic.

So if you're working on a big, long-running series... even like Sonic, when I did my first Sonic game, which is Sonic 3D Blast, on the Saturn and PC, I was taking my main reference from the Japanese version of Sonic CD, because in my opinion, it's an absolutely brilliant score and brilliant game music. I thought that was the excellent blueprint for Sonic.

So existing brands that go through multiple iterations and versions, yeah, I think it's still right to keep in with the overall style guide if you like, but you can still play around within that, I think. Look how Sonic's evolved as a character, as a game, and the music along with it.

Well...

RJ: Well maybe... (laughter) But it has changed!

I wanted to ask you about interactive scores, because not a whole lot has been done with it yet, necessarily, or it seems like there's a lot more that could be.

RJ: Firstly, I would politely disagree with that statement, because... actually, I won't say the name of the website, but there was an interview with me, and one of the questions was "There is a lot of talk about interactive music, but it doesn't mean anything." So, a quite interesting perception, and probably picking up on what you just mentioned.

I think over the last three to four years, there's been a lot of interactive scores, and whether they're not publicized or whatever, but people maybe don't know about them. The most interesting thing about that is that if they're done well, the gamer may notice the changes less than if they're incredibly obvious.

There was an interesting conversation I was having with Russell Shaw, composer at Lionhead who's been working on Fable and Fable 2. He said that he did a focus group test when they were working on Fable 1 of really, carefully interactive music changing seamlessly and smoothly, or two tracks... I don't remember what it was, but let's say "exploring" and "battle music," cut really brutally. The gamers preferred that method, because it was obvious.

Another composer I know on a big title which I'm not going to mention was going through an awards nomination process, and the nominating panel couldn't tell that the score was interactive because it was done so well and so smoothly and so cleanly that it wasn't that obvious.

But if they videotaped themselves playing through the whole game and then did it again differently, you'd guarantee that the score would play out completely differently.

It's a really great question. I think that a lot of composers are doing it so well now that it's smooth and clean and plays underneath the game in this seamless way that we are doing our jobs right.

If it's really obviously done and you're just hard-cutting two stereo tracks, that's what we as composers are trying to get away from, because as a movie soundtrack, the score would play beautifully underneath and support it and etcetera, but it should never get in the way.

That's what we've been trying to do with games. I think there's a lot of it happening, and I think we'll see more of it in the next two to four years, because we've got great tools, and everyone's aware of it. That's why I'm considering giving talks about how to write the stuff.

What, then, do you think is a good balance for that? When is it appropriate, and how should it be... in fact, do you have multiple different modular music that can build and subtract from itself, or do you have things in different octaves?

RJ: Well, the way I do things, it really depends on the game, because every game should be approached differently. I do a lot of action games, and I do quite a few action-adventure games as well.

In action-adventure games, you've got situational music. Let's say "walking," "running," "exploring," and that kind of thing. Then you're going to have battle music, whether it's a war thing or if it's a hack-and-slash thing or whatever, but you're going to have combat music of some shape or form.

You can have different levels of combat music, depending on the number of enemies. You almost certainly have to have some kind of boss music, some cut scenes, and etcetera.

I look at that, and I think, "What do I want the player to feel, and how do I do that interactively with the score?" When you're just looking around -- looking at Oblivion or something like that -- and you're looking around at this beautiful landscape, you might go into a battle very quickly, but the way I want to do that interactively is have a musical transition, or rise or whatever that sounds very musical but then goes into a big battle scene, rather than hard-cutting two tracks, because I think it can be done better than that.

So my approach is always... I do quite a lot of layered soundtracks. A lot of my stuff has three or more layers of sometimes the same piece of music, if you like, and sometimes three different pieces of music all layered on top of each other, which you can change at any time. That's noticeable enough to the player, but you can really ramp up and down the tension in a split second, according to the gameplay, and it works fantastically well.

I haven't noticed it as much recently, but in the past, when battle music was brought in by your proximity to the enemy, sometimes you could get in and out of that range and make stupid things happen. How do you deal with those kinds of considerations? I know that's not on your side, the implementation, but...

RJ: Sure. Well, sometimes it is. I mean, I try and do as much of my own implementation as I can, but obviously it's down to the programmer, or depending on the toolset, something like that. The choices of how we use interactivity with music are kind of between lead coder, lead designer, and composer, really.

I could say, "Sure, my music changed dependent on how far I am from an enemy, or a number of enemies, or the ferocity of an enemy," but it's about these hopes. There's no real set rules for this. It's kind of down to personal implementation, and it does depend on the game.

You look at something like Mario Kart on the N64, and even thought that was done with a sound chip -- there's no CD drive -- the great thing about that is the tempo of the last lap. That works within the race. It's simple, and it works so well. And of course, CD-based music or any disc-based music, you can't really do that easily, because it's a different beast.

But I think it's a question of... now we can produce good interactive scores. Now we're looking at... well, it's the creative choices that are going to be the most important thing in the next two to four years, I believe.

What we're going to hook into in the game code is... Is it about the speed of driving our car? Is it about how rapidly we're firing our gun? These kinds of things. What kind of feedback do we want from the music? It could be very simple things, very complex things, or the number of hooks we put in to change the music. It's a complex puzzle, and we're still all trying to solve the puzzle, really.

What do you think about licensed music in games? I'm personally not a big fan of it, myself.

RJ: Being honest, back when it first started around '95 or '96, I think most composers were worried, "Oh no, the record industry is taking over." At that time, I was an in-house composer, and the music industry made it seem like composers wouldn't be needed.

From a personal point of view, when I heard Wipeout, I thought it was awesome, because it was chosen so well. The bad thing about licensed music is that often, the completely wrong choices are made.

From a personal point of view, when I heard Wipeout, I thought it was awesome, because it was chosen so well. The bad thing about licensed music is that often, the completely wrong choices are made.

I don't think people have the game in mind enough when they're choosing artists, bands, DJs, and whatever to license tracks or even create new tracks. All of that is going to be marketing-driven in some sense.

Whatever an audio director will say, there will always be an element of, "We want this band, because they are this band, or this singer, or whatever."

I think Wipeout is still the finest example. I think all of the Wipeout soundtracks have been so fitting for the game. Apart from that, nothing's completely blown me away, to be frank.

But I'm a big fan of stuff like Rez. When Mizuguchi works with those artists, they're producing their own custom tracks. I think that is the way we should be going, because a lot of these guys are gamers, and they want to produce stuff themselves, rather than, "We want this track and this track."

A good thing about licensed music is that we wouldn't have a lot of music and rhythm-action games without a lot of licensed music. So that's a great thing. I'm not a fan of putting it in for the sake of it, and I'm not a fan of... I mean, for a racing game, if they fill it full of rock music, what happens if you don't like rock music?

About the rhythm-type games...it's funny, because it's true that's where they are now, but it was popularized by PaRappa the Rapper, which had original music.

RJ: True. Good point.

Have you ever thought about doing something like that yourself?

RJ: What, working on rhythm-action games?

Yes.

RJ: I had a small involvement in Samba de Amigo, because there's a track on there I had on there from Sonic R, actually -- Super Sonic Racing is the hardest bonus track that you get in the game, and I was involved in the sequencing of the maracas.

So I was playing through the earlier stages of the game and getting used to the game, and you know, I'm not a game designer. I don't know a lot about game balancing. But I knew what I was supposed to do, and I thought, "Right."

And we were using fairly basic sequencing packages to create the on-screen icons, so I did a basic mock-up of what would work with the track, and Sega of Japan kind of tweaked it from there.

I also work on the SingStar series, in more of a technical capacity, and also on some of the EyeToy series for Sony. There's quite a few music games in that, and apart from writing the music, it was fairly involved.

There's a little mini-game in there called Air Guitar, which is on EyeToy Play 2, and that was long before Guitar Hero. And that's just with a camera. There's no physical controller, so the music had to be written in a very precise way so that it was fun to play with all the licks and riffs and stuff. I would love to do more of that kind of work.

Sony's EyeToy Play 2

My girlfriend, who is a game designer... we kind of toyed with the idea of doing something together, because she's really into rhythm-action games, and she's a designer and I'm a composer.

Maybe we would look at doing some kind of other web-based or downloadable thing, because neither of us are coders. But I have so many ideas, because I understand games, and I understand music so well, and I understand what makes a rhythm-action game fun.

And it's not necessarily because it's got some band in there. That makes no difference at all. It's about how much fun it is to play, and how well it's executed. Rez has got to be one of the finest examples of that, in terms of musical feedback and how it works.

It's just absolutely brilliant. And I'm a big fan of Guitar Hero and Rock Band and those kinds of things. They're bringing quite a bit of family audience as well, and it's been executed very well with the music in mind.

There aren't a whole lot of games out there that are composer-driven, which I don't know if it's down to people feeling that it's not an important part of the process or something or what, but aside from all the games that NanaOn-Sha has done like PaRappa the Rapper or...

RJ: Um Jammer Lammy.

Yeah, all those types of games. There aren't a whole lot of games that have been driven by that sort of thing.

RJ: That's very true.

So if you did manage to do that, it might be rather nice.

RJ: I'll see what I can do. I'd definitely love to do it. Part of the problem is that a lot of composers now who work in the games industry -- especially the orchestral composers -- to be frank, they don't really play games. They don't. That goes back to one thing we talked about earlier, about film composers and stuff. They've never played PaRappa, so they don't know that interaction, that kind of magical balance between gameplay and music.

And I kind of really, totally get that. I've worked on all this stuff. When I was able to work with just a couple of guys, I can't do artwork, and I can't do coding, but I'm sure me and maybe my girlfriend could come up with some pretty hot ideas, because we know the kind of things that are fun and make great gameplay. And you make a great point about being very composer-driven -- the music drives the game design and how it shapes together.

Yeah. The only other example I can think of is...you know Yuzo Koshiro?

RJ: Yeah.

With his company, Ancient. He just happens to be a composer, also. It's only composer-driven by happenstance.

RJ: Yeah. (laughter) One funny story is that when I went to Tokyo once, I went to see Mizuguchi-san's team, and they were just starting out on Rez. A lot of people in reviews -- it's just now being rereleased on Xbox Live and stuff -- they're saying "It reminds me a little bit of Panzer Dragoon," but what they don't realize is that they were actually using the Panzer Dragoon engine while they were building it. The first time I saw it, the music was awesome, but it had a really bad texture and a few rocks coming towards you, and that was it. But I totally got the game immediately, because the music was so well-done.

There was an early tech demo, when it was called K Project, which was extremely confusing to people...

RJ: Yeah. K Project, yeah.

And they used some of the music from Panzer Dragoon Zwei, I think, in the trailer, so that even further confused people. It's like, "Aah! What? What's happening?"

RJ: Yeah, I've had a lot of fun rediscovering that on Xbox Live recently. I think it's a terrific game. And I was a huge fan of PaRappa. That was a stroke of genius. And Space Channel 5 and those type of games.

Sony's PaRappa the Rapper

And the downloadable games, too.

RJ: Yeah. I think that's a good thing, because that's what makes video games fun. I was having a conversation with someone the other day. It's like... a lot of the games that are out now, they're not fun. I don't think they're fun. I mean, people enjoy playing them. They get enjoyment out of them.

But if I want to run around... a lot of them are simulating real life too much, in my opinion, whereas something like Super Mario Galaxy, you can't do that in real life. I can't play tennis against Ulala from Space Channel 5. That's what, to me, video games are fun. That is the real reason. I want to do something really crazy and really stupid and really fun and silly.

That was something that was really refreshing about Outrun 2 and Outrun 2006 when they came out, because it was just very... you couldn't really do this, but it's fun, and you're collecting hearts in your car.

RJ: That's right! (laughter) And trying to please your girlfriend. The funny thing about it is that I was playing it with my girlfriend two weeks ago in London -- Outrun 2 SP Special Tour, I think is the edition.

There were two guys playing it, and they were trying to drive it really seriously and take the corners, not realizing anything about powersliding. So we just got in and rocked it, you know, 45 degree powersliding around every corner, because you can't do that in real life. It's just such a brilliant gameplay mechanic, and it's one of my favorite games. I play it all the time.

And the music was very well-integrated for that as well, just because it was very...the right kind of over-the-top.

RJ: Yeah. What I didn't realize about that, when I was doing the remixes for Outrun 2, the original Outrun... I played that when I was 12 or 13 years old. It really rang true for me. That was the first thing I really remember well. It was actually composed so the music would change where an average player would do the branching at the end.

I mean, it wasn't interactive, but they timed the music so that when you went down the end of one course and you branched into the next course, the music would go into a different chorus or something like that. I didn't actually know that until I was remixing it, because all the tracks are actually about eight minutes long. So even in those days, it was being thought about.

Interactive music: it's been around forever!

RJ: Yep! Exactly. It's old school.

Sega's Outrun

Did you get to do any vocal tracks for Sega Superstars Tennis?

RJ: No, not for this one. (laughter) Which is probably good for the fans. I was reading something the other day on some U.S. website, and they were saying something about the worst Sonic games of all time, and I think Sonic R was number one. They said, "What the hell is this music?" It doesn't bother me, because Yuji Naka likes it, and the fans like it.

Yeah, actually, I completely disagree on both counts. The music is ridiculous, with the lyrics and stuff...

RJ: I agree! (laughter)

But I can remember them all. That's something. A friend of mine here who's freelancing today... he and I can recite the whole songs.

RJ: There's a couple of interesting anecdotes about that. Yuji Naka wanted that kind of thing, so who am I going to argue with? He's like God to me. And I really understood what he wanted, and also because of all the J-pop culture anyway, that's really what was happening in game music at the time.

I think after I'd written the first test track, which was the Super Sonic Racing track, he loved it so much. He's put it on like five compilation albums, and it's in Super Smash Bros. Brawl as well, I found out last week. And that's something I wrote ten years ago.

The second funny story is that I met my girlfriend as a result of Sonic R, because she's a huge fan. She's a game designer, and she was a huge fan, and someone who knew me called me up and said, "Hey, she's great." She's a huge Space Channel 5 fan, too.

That makes sense. Did you write the lyrics to those songs yourself?

RJ: Yep.

Oh man. What was the inspiration?

RJ: All the inspiration came from the levels themselves, really. I had a bunch of paper design docs and some concept artwork, and once they kind of... they had a short list of names for the levels, like "Reaction Factory" and "Regal Ruins" or whatever it was called.

I had to look at the level and basically write a song that would lyrically represent something in the level. So for Regal Ruins, it was the "Back in Time" track, because it's all Egyptian ruins and things like that, and "Work it Out" because it's in a factory industrial setting.

I didn't make the connection there. (laughter)

RJ: Maybe it's not that obvious, but it was the way I was thinking behind it. I didn't want to write a bunch of songs about Sonic, or any of the characters, per se, except for Super Sonic Racing, because that plays in the game when you are Super Sonic, the yellow character. They're all based around the levels, but they all had to be fast and kind of uplifting and sugar-coated and do what they say in the tune.

Did the music test as well in both markets? Since it was going for kind of the J-pop thing, did it...?

RJ: Good question. Originally, we were talking with an artist from Germany called Blümchen, which translates into "blossom." She was only like 16 or 17 at the time of making the game, and her record company found me, and they wanted to write all this stuff, and this and that. We didn't actually make the deal.

But Naka-san said, "Go and find a vocalist," so I found a vocalist I worked with before, TJ, and she's become a bit of a legend within the Sega fraternity as well. She did MSR and all that stuff with me as well. We did that stuff and sent it back to Japan, and it got the nod from Yuji Naka, and that was it. We went with it.

Sega/Traveller's Tales' Sonic R

We didn't think about the markets too much, honestly, because I don't like doing different soundtracks for different markets, even though I think it can be appropriate for some types of games. I mean, the Sonic CD Japanese version I think is just so much more appropriate for the game than the U.S. version, but then again, maybe at that time I didn't know the U.S. market as well as I do now.

We just went with one version and gave people the option to have instrumentals as well, which... of course we're not going to force them to have the vocals. But whenever I'm playing at Video Games Live or something, the fans just always talk about that game. And it came out in '97 or something? It's a long time ago.

Do you think that vocal tracks could ever be back seriously in games?

RJ: Maybe not to that degree. Not that kind of J-pop-esque kind of way. No, I don't think so, and that's probably right, because look how games have stylistically changed themselves in ten years.

Even though you get songs in the Marios still, you're now getting all the Gears and Halos where you wouldn't have done in those days. So I don't think vocal tracks, in terms of singing in that right will... but you know, some stuff... the human voice is very valid in video game soundtracks as an instrument, and is being used very, very well, and moreso at the moment.

In Highlander, I'm working with a Scottish singer, and we're actually singing the title track in Celtic, or Scottish Gaelic, rather. There is a connection that the human voice makes with any audience, whether it's in games or in cinema goers or whatever. It makes an instant connection. I think that has a very valid place in games, but maybe back to the Sonic R days? I don't think so.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like