Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Castlevania veteran Koji Igarashi made $5.5 million for Bloodstained, and there are a lot of lessons to be learned from how he did it. Here's an analysis based on an extensive conversation with him.

Last week I published an interview with Koji "IGA" Igarashi, well-known producer of the Castlevania series -- who's now back in the news because he ran the most successful Kickstarter in video games yet: $5.5 million for his spiritual sequel to the franchise that made his name: Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night.

The Q&A was long, so I decided to break out some of the most salient bits. Very few will be running such massive crowdfunding projects, but the wisdom of a veteran producer, known for his conscientiousness -- whose numerous Castlevania games reputedly came in on-time and on-budget -- is useful to consider.

I asked Igarashi about his approach to stretch goals, in particular. The project blew through them at a prodigious rate, and some really stand out, like one for a retro prequel game. He brought up that example himself before I even had a chance to ask: "we basically ate through any buffer that we had to be able to offer that as an option," said Ben Judd, Igarashi's agent, during the conversation.

Said Igarashi, "The general rule is that the money that you raise on Kickstarter is half of what you're going to get. So we set a lot of stretch goals that were about $250,000 apart, which means that the actual development budget that we would get to spend would be $125,000 -- so not a lot."

"As we planned it, the earlier stretch goals had a bit more of a buffer. And every once in a while there would come a stretch goal that would use up some of that buffer. And the needle came closer and closer to the reality."

The stretch goals in question -- from an insane laundry list of them.

Judd worked extensively on the campaign, and added some color about how careful the team was about planning stretch goals: "So it was having a very daily planned-out organic flow of these stretch goals. Of course, from the campaign side, I was a part of that -- almost from a two or three [times] daily basis, we were looking at the user comments, we were taking that feedback, we were talking with the production side. ... All of that was done through very long planning that was done on a very flexible basis."

Note here that Judd alluded to a huge number of daily meetings. The fact of the matter is, many devs do not consider that running a Kickstarter is a full-time job for at least one person, for its duration. I've heard that many times now, from a variety of sources -- large and small.

One thing that struck me is that Igarashi did not set aside any of the Kickstarter money:

"We ended up using it all. It's all gone. There's a little risk that comes with guaranteeing you're going to put in modes and things into the game that guarantee that you're not going to have as much of a safety net -- but it never, ever even occurred to me to think of this as profit we would save again for a rainy day, as if this was a preorder or something like this," Igarashi told me.

The fact is, he has an unknown amount of backing from an as-yet unannounced publisher (which we all assume is Deep Silver, as it filed a trademark for the game's title in the West on Igarashi's behalf.) So the core game development is covered, presumably including potential overruns.

"For the campaign, as we've said, a budget was guaranteed by back-end investment. So we knew that when we got the additional amount, that [investment] would complete the core game. And so that was the core game that we had in mind; we could make it, for sure, with that budget. We had already planned it out, what the assets were going to cost, etcetera," Igarashi said.

The stretch goals, however, promise a game with almost too many modes and options (including three playable characters, for example.) Stretch goals aren't just attractive to backers, though. They ensure the future of the franchise: "And again, as a starting point, putting all this emphasis on content, while it is a bit risky, it will help us hopefully shape an even better second game, which is obviously the end goal for most productions," Igarashi said.

That's an important point to sit with for a second: Igarashi is thinking far ahead. He has both the expertise to do so, having made so many games in the same franchise -- and the luxury of being such a well-loved creator. But it's clearly never too early to plan for the future, for any developers.

He told me that modes that turn out to be popular may be emphasized for the sequel; those which are unpopular may be cut entirely the second time around.

Those are Igarashi's words. While I asked him about both presumptive Bloodstained publisher Deep Silver and Konami, where he worked for years, he seemed more interested in talking about his backers:

"From my perspective, these are people that are helping me create the best game I could, and I am promising to make the best game I could with it -- not make most of the best game I could, and save some money off for a rainy day."

The campaign's concluding message to backers, as delivered by its heroine, Miriam.

Igarashi is balancing on a knife-edge, in a way; the majority of people who backed this game are probably Symphony of the Night fans. But Igarashi has done a lot with that game's basic formula over the intervening years since its release, and it's impossible for him, creatively speaking, to just retread that ground and deliver a straight sequel to an 18-year old game.

"Maybe for people expecting a Symphony of the Night 2, this game will not be that; but the core foundation of what makes his games his games is definitely going to be there, and it's going to be what sort of icing that we put on the cake that's going to be different -- that makes for a new sort of feel to the gameplay," said Judd.

But something that is really remarkable about the Bloodstained campaign is that Igarashi was able to extract a very high average spend from his backers: at $5,545,991 raised from 64,867 people, that works out to over $85 per person -- when the digital download-only tier is only $28.

The fact of the matter is: Kickstarter allows Igarashi to sell people on buying a game relative to their means and interest, not industry-standard price points for digital and physical games.

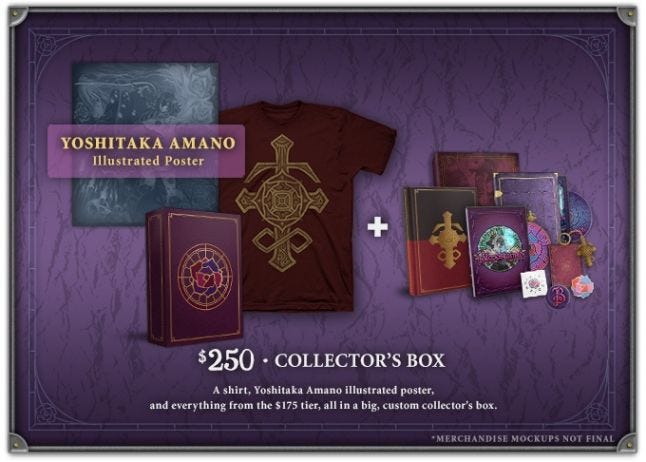

"Those people want what they want, and they're very passionate for those games, up to the point where they would spend $100, $200, $300 on a collectors' edition, or something like that, which totally fits within the Kickstarter scheme of things -- 'less people, more money' helps cover that budget," he said.

Igarashi has an advantage: It's not just that nostalgia sells, but that his core audience is likely to be older and have more disposable income. Symphony of the Night came out in 1997. Someone who was 15 when it was released -- which seems like a good target age for the PlayStation audience of the time -- is 32 or 33 now.

There's a great deal more from Igarashi and Judd in the full-length Q&A, including some discussions of game design, another example of how Igarashi carefully considers the game he wants to make, balanced against the desires of his audience and what he knows will work with the resources he's got.

You May Also Like