Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Accessibility isn't a single task; it's a process that touches every aspect of game development, including community management.

Accessibility isn't a single task; it's a process that touches every aspect of game development, including community management.

At GDC 21, 'Can I Play That?' editor-in-chief Courtney Craven and CIPT accessibility specialist Stacey Jenkins took to the virtual stage to give game developers and community managers best practices for creating community content that is accessible in both form and function.

As both Craven and Jenkins explain, crafting your community management plans without considering how accessible your content is to a wider audience can quickly exclude people from participating in community events or even engaging with your game.

"Ensuring your community content is accessible allows everyone to engage with your brand and is also a big step towards a more inclusive and welcoming community," says Jenkins. Craven and Jenkins make the point that accessibility considerations benefit more groups of people than most would first think, including disabled people, parents busy with childcare, people exhausted after a long day, or even just those with slow internet.

"It's really important to consider how users might be interacting with your content. Are they using a phone? A PC? Are they using assistive technology?" says Jenkins. "We want to think about how we create memes for people without sight. How do we make sure our game trailers are accessible for deaf or hard of hearing people? How do we run our online events with blind and low vision viewers?"

It's incredibly easy to unintentionally let your own biases make your content less accessible, which is exactly why those questions should touch every part of the process, from content creation to publishing.

Craven makes the point that most folks creating content do it largely from their own perspective. They note that there's an inherent bias everyone has to first consider only how they themselves would experience whatever they are creating. It takes practice and careful attention to move past those biases, which is where the best practices for accessible community management come in.

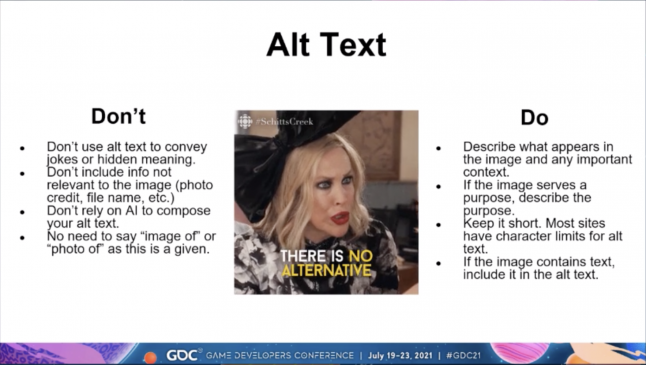

The advice Craven and Jenkins share in their full talk ranges from tips to make written content easier to parse for a wide audience to more tool-specific advice for creating captions or publishing screen reader-friendly content.

On a general writing front, Jenkins suggests keeping sentences short and using simpler words with fewer syllables where possible. Be mindful of jargon and how familiar your target audience may be with certain terms, something particularly trick in the acronym-heavy world of video games. Craven adds that language should always be gender inclusive, avoid euphemisms for disability ("...things like specially-abled or differently-abled. Just say disabled, or person with a disability."), and include content or trigger warnings where appropriate.

When taking on social media posts, the go-to formats for many memes or trends online can spell trouble for screen readers, and make the actual content of the post completely unintelligible to people that use one to browse social media.

In most cases, a screenshot can be worth a thousand words. Jenkins offers up a couple of tweets from the Xbox brand account as an example. The first features a thought bubble created from ASCII symbols with a single emoji in the center. To a screen reader, that tweet reads "Oh Gaming" rather than the message Xbox intended to convey.

The other tweet, they explain, takes a more accessible approach by sharing a screenshot of several emoji arranged to look like Nether Portals from Minecraft and using Twitter's built-in tools to describe the image through ALT text. The result is a joke about Minecraft that can be enjoyed regardless of how its community accesses Twitter.

Captions, meanwhile, are a feature that have thankfully become more and more commonplace across different forms of media. However Craven, a professional captioner by trade, warns not to settle for "good enough" when it comes to captions. Auto-generated captions in particular, they note, are generally only accurate 60 to 70 percent of the time, and that's only if your speaker speaks perfectly throughout and doesn't use any of the jargon video games use very commonly.

Reading captions requires some mental multitasking so displaying too much text on the screen at once makes it more difficult for someone to watch a video while reading or, in a video game, continue what they're doing without having to first stop and read a wall of tiny text.

With that in mind, Craven suggests that captions should be limited to 37 characters per line, and, at most, 2 lines of text at any given time. Captions shouldn't be censored if the voiceover itself isn't censored as "deaf and hard of hearing people deserve the same access to information that hearing people and anyone else watching the video have as well."

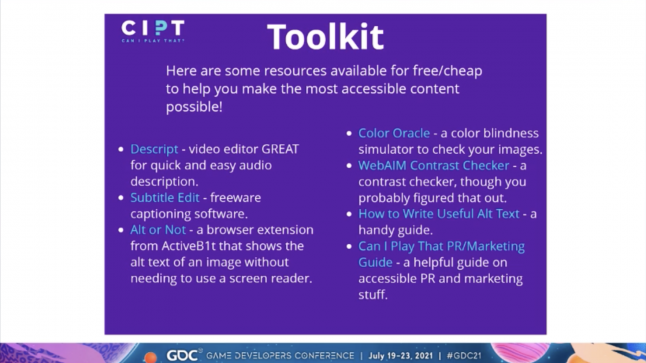

Their talk concludes with a useful list of free or low-cost resources community managers and the wider development community can use to implement some of the above features into their content. An image with description of each is above, and the list includes the tools Descript, Subtitle Edit, Alt or Not, Color Oracle, WebAIM Contrast Checker, How to Write Useful Alt Text, and the Can I Play That PR/Marketing Guide.

"It's also good to remember that no one expects you to get it right immediately or all the time," closes Craven. "There's always room to learn and improve. Stacey and I forget alt text sometimes, I forget captions sometimes. It happens. The important thing is that you remain open to feedback and you're always aiming to improve the inclusion of your community and content."

Read more about:

event-gdcYou May Also Like