Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In-game ad deals can benefit both game developers and advertisers -- experienced game lawyers Boyd and Lalla discuss business and contextual considerations for in-game advertising.

February 11, 2009

Author: by Vejay Lalla

[In-game ad deals can benefit both game developers and advertisers -- and veteran game lawyers Boyd and Lalla discuss business and contextual considerations for in-game advertising.]

Advertising in games is currently in a stage similar to internet advertising in the late 1990's -- the research and development phase. As such, many deal terms during negotiations between game companies and advertisers -- including one of the most important to all parties, price -- are in flux.[1]

Ask three different business executives in the industry the same question about negotiating in-game advertising deals, and you're likely to get three different answers.

This article pulls together some of the more uniform aspects of advertising deals in the game industry, and discusses the major issues facing both game companies and advertisers as they contemplate the pros and cons of game placements -- and negotiate in-game advertising deals as they move forward.

Before we launch into a discussion of the business and legal issues that game companies and advertisers may need to know moving forward, a brief review of the current status of advertising and games may be helpful to frame the discussion.

As most game industry veterans are aware, the game industry is rapidly overtaking other forms of entertainment to become a financially and culturally dominant force in the United States and abroad.

The global games market has been booming in the last several years. According to industry analysts such as DFC Intelligence, between 2000 and 2001, the U.S. games industry grew from $6.6 billion to $9.4 billion. In 2007, that figure was up to a record-shattering $17.94 billion -- and that doesn't even include PC game sales or online revenue. Our most recent figures show that the global video game industry revenue was approximately $40 billion in 2007.

Globally, the worldwide interactive entertainment industry is on track to achieve revenues of $57 billion as early as 2009.[2] On the individual game level, we have numbers like the best-selling U.S. debut of any entertainment product ever: Last year's launch of Grand Theft Auto IV generated 500 million dollars in revenue in one week.[3]

Given the level of growth and the relative figures to other forms of entertainment, games have become increasingly attractive areas for marketing communications by advertisers. Research firm Parks Associates estimated advertising in the game industry to be $370 million in 2006, growing to $2 billion by 2012.[4]

The proposition is attractive to the game industry because it offers an additional revenue stream beyond the traditional model of revenue from retail sales, and it is also becoming more important to advertisers who are looking for new ways to reach consumers, particularly the coveted young male audience of 12-34 years old who spend more and more of their time playing games rather than watching traditional television.

Advertisers are no longer spending their advertising dollars on traditional media purchases such as television, where consumers are using their DVRs with ever more frequency. They are expanding their digital media budgets, and in many instances, this includes in-game placements.

This article focuses on the business and legal issues surrounding advertising agreements in the game industry. Specifically, we address what deal points are most negotiated, and what variations or fallback positions are possible for these negotiated points. The article examines these issues from both the advertiser's and the game company's sides of the table.

This includes the tensions between advertisers with their traditional business models and need to protect their branding and intellectual property -- and the ever-growing and developing game industry, plus the importance to game companies of flexibility in their approach to advertising.

The primary objective, in many instances, is to include seamless advertising that doesn't interrupt or otherwise interfere with the player's enjoyment. We then discuss how the parties measure success, and whether including advertising in games is always the best choice for both advertisers and game companies.

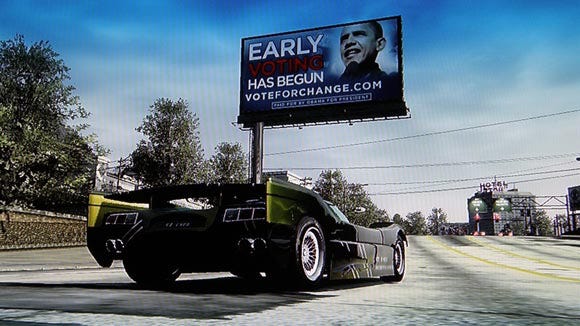

One of the most critical deal points is the placement of the advertising in the context of the flow of the game. Placement is a complex decision that involves hard thinking by both parties on which game to advertise in, the places most suitable for advertising, any exclusivity for the advertiser in the game, and the choice of whether such placement will be fixed or dynamic within the context of the game and advertising for the brand.

The game itself is the first critical choice. For instance, brands traditionally associated with sports advertising are most appropriate for sports games. Certain youth brands may aim at skateboarding, platforming, or similarly themed games. Advertisements are intended to create brand awareness for the target demographic -- but if the audience feels the brand is out of place in the game, the advertisement may have the opposite effect.

Aside from the choice of game, there are still many more decisions to be made. Is the advertiser looking for static advertising or dynamic advertising? Static advertising is a fixed placement in the game at launch and stays in the same form after release of the game indefinitely. This type of advertising does not rely on an internet connection to broadcast the images into the game -- but it also cannot be changed after launch.

The disadvantage of dynamic advertising is that it requires an internet connection to be broadcast into the game -- but it also has some particular advantages. It is a flexible branding image where elements can be interchangeable. It also provides advertisers an easy method to measure and collect valuable advertising data on consumers -- and potentially even consumer behavior based on impressions, keywords, clickthroughs, and other kinds of information.

As discussed, it's also easier to correct potential issues for both parties in a dynamic placement. If there is a problem in a fixed placement with a branded image, or with any claims or other copy in the advertising, a recall may be the only solution to the advertiser -- and the game company will likely resist it as much as possible. As discussed later, dynamic advertising is typically cheaper, and is therefore fast becoming the common choice among many advertisers.

[1] For clarity, throughout this article, the authors deliberately use "game companies" to mean both publishers and developers and "advertisers" to refer to both advertising agencies and brand holders.

[2] http://blogs.pcworld.com/gameon/archives/007189.html

[3] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Theft_Auto_IV

[4] http://www.clickz.com/showPage.html?page=3626301

After the static or dynamic decision, the second important choice for both parties is whether or not the placement is exclusive to the advertiser. For in-game advertising, the term "exclusivity" is broader than most people generally understand.

Clearly, an advertiser can be the only advertiser in a game -- but this type of exclusivity is often prohibitively expensive. If advertisers are looking for a thematic approach, as is being seen with television and film -- where the product placements are conceptually intertwined in the story of the game -- rather than pay for exclusivity as the only advertiser in the entire game, advertisers typically should consider asking for category/industry exclusivity as an option.

This means an advertiser may be in a game with other advertisers, but it will be the only representative of its consumer category or industry. An example of category/industry exclusivity would include being the only soft drink promoted in a game. When defining this type of exclusivity in the contract, both sides should be careful to spell out what is included in the brand's category for exclusivity purposes.

While a game company may want to narrow the category -- for example, to soft drinks, in order to bring in more advertisers and dollars, a major advertiser in the soft drink category like Pepsi would also want to ensure it shuts out brands in related categories such as juices, sports and energy drinks, and even teas and water products.

In addition to a careful definition that is beneficial to both parties' concerns, another issue that comes up is whether or not the parties should include a specific list of prohibited competitors to clarify the deal. In many cases, advertisers will try and avoid this, and seek as broad of a definition as possible -- while, for a game company, specifics are best to be included so game companies know what they can or cannot do from a business standpoint in selling advertising.

Payment is clearly one of the most hotly negotiated deal points in any transaction, and this is certainly true for game advertising as well. There is always a back-and-forth tension between the game company and the advertiser with respect to the two biggest payment issues: (a) the timing of the payments and (b) the refund process should conditions not be met or should the placement not be included in large part (or at all).

With respect to the timing issue, the game company has an interest in getting a flat fee payment as early as possible in the process, as these payments can help fund development for more robust features or help repay development costs. On the other hand, advertisers typically like to pay for results -- and specifically like to pay only if and when the game is launched and the placement is what was intended.

A common compromise that can be included in the agreement is to agree to split flat fee payments between (a) mutual execution of the agreement and (b) a later date, such as final approval of materials in beta or at launch of the product.

Still, paying a flat fee is not the only way that advertisers pay for advertising in games. It is also possible to pay per unit shipped on a quarterly basis. In this case, advertisers should require both quarterly statements to review the volume and fees generated by the game company, and include in the agreement an audit right, allowing the advertiser to examine the game company's books and records pertaining to the sales generated, to ensure accuracy.

As a game company, the more limited the advertiser's audit right -- e.g. not more than once a year, and limited solely to verify the accuracy of the payments -- the better, as game companies would rather not concern themselves with constant audits during the course of a year by a potentially aggressive client.

Static advertising packages range dramatically in the industry, and are often based on projected (or actual) units sold, integration complexity, and the final form of the game. Even entry-level price points are usually in the several thousand dollar range. Some exclusive static placement packages in AAA titles can be several hundred thousand dollars.

Dynamic advertising allows for more complex payment and measurement systems allowing for payment based on impressions, similar to web advertising. Because the advertisement is ephemeral, the entry price point is usually much lower than static advertising. The cost for both types of advertising goes up if the advertiser requires any exclusivity, and may depend on the types of games if the advertiser is purchasing in a game network.

For example, if an advertiser does a deal with a an in-game advertising company like Massive, who is able to place branding in its network of games, Massive will likely include language that gives them the flexibility to swap out games. However, an advertiser may want to include some language protecting against this, if the swap may be aimed at a different audience than originally intended.

The approval process for in-game advertising is second only to price as a key element of the negotiations. This is true for a dynamic advertisement before it is broadcast, but it is critically true for static advertising, since that advertising is often included on the game disc and cannot be changed after launch without a recall. Furthermore, as described above, there is usually much more riding on static advertising in terms of marketing dollars.

For advertisers, the most valuable and protected assets are their trademarks and brands, and they are therefore very protective about quality control and the placement of their names, logos, and other trademarks and branding in advertising.

This causes some real tension between traditional advertisers who view their brand as their most valuable asset, and game companies who need timely approvals to stay on a production schedule, and some flexibility on the creative side to modify elements of placements to create a fluid and dynamic game that gamers will want to purchase.

Ultimately, the branding elements must look correct given the brand guidelines furnished to the game company, and the surroundings also must not take away from the brand presentation. For instance, family-friendly or major advertising brands typically will not want -- or expect -- to be in violent surroundings, and many major media agencies who purchase advertising will include standard contract language in media insertion orders providing that their advertising will not be adjacent to violence, obscene materials, racism, or other explosive subject matter.

The two overriding elements in the approval process are, (a) when the approval occurs and (b) what the parameters are on how it occurs. After the development team receives the brand materials, it begins to integrate those materials according to a pre-existing plan. The advertiser will want to confirm the placement, and also confirm that it does not change in later iterations of the game during the development process.

For instance, advertisers often want approval over the placement in alpha, beta, and launch versions of the game. Because this approval is so important, it is in both parties' interest to have the brand materials sent to the developer early in the development process.

A second question after the timing of approvals is -- how should the approvals be done? In theory, the brand holder should send the materials over in plenty of time, those materials should be perfectly integrated into the placement, and the advertiser should approve the placement.

In practice, there are several places this process can break down, and so the parties should both be asking the following questions when negotiating the approval. These are all the elements that can and do go wrong on approvals:

How many days should it take for approval?

What happens if the placement is not approved?

What happens if there is "silence" on the advertiser side and what happens if an approval is not sent over from the developer on time?

On the questions above, the authors give the following guidance: On timing, five business days should be plenty of time to approve an advertising placement, although many traditional advertisers have corporate bureaucracies that can delay the process. In these cases, game companies should always ask for and try and include contract language that "the advertiser's approval is not to be unreasonably withheld, conditioned, or delayed" as it obligates the advertiser to be timely and reasonable in its approval process.

With respect to the scope of the advertiser's approval rights, game companies should try and limit the approval by having the agreement provide that the developer will follow the branding guidelines of the advertiser, without needing approval except for any material deviations from the branding guidelines.

With respect to the scope of the advertiser's approval rights, game companies should try and limit the approval by having the agreement provide that the developer will follow the branding guidelines of the advertiser, without needing approval except for any material deviations from the branding guidelines.

Although game companies do want to ensure correct placement, language simply requiring consultation and following branding guidelines is more reasonable and places less of a burden on the game company and leaves the creative process to the game developers. For an advertiser, this may be more company-specific -- if there are uniform company guidelines for branding approval.

Advertisers should keep in mind in the gaming context, particularly for a fixed placement, that it would also be helpful to include more specific contract language -- providing explicitly that the advertiser has approval over all versions of the game (e.g. alpha, beta, and launch) and the placement shall not materially be altered by the developer after such approval except for bug fixes, game balancing, and polish.

In a dynamic placement, due to the ability to swap out a placement, advertisers may be amenable to more flexible language, but should still ensure that the game company follows the advertiser's written branding guidelines -- and meaningfully consults with the advertiser throughout the development process, particularly to confirm any product attributes or claims made with respect to advertiser's products and services. Even in dynamic settings, advertisers should try and ask for approval over the placement "in game conditions".

Overall, with respect to where approval is needed, if the placement is not approved, the developer should state contractually that it is the advertiser's obligation to be very clear about what would make the advertisement acceptable. Silence from the developer on sending a placement or silence on the approval end should not become tacit acceptance of the placement, as it is not in either party's interest.

The parties should ensure there is a detailed process set up in the agreement with a contact person to call on both sides if the approval process is not moving forward -- and the game company should ensure that this contact contractually has the authority to approve materials on the advertiser's behalf.

Games are not like print or television advertising, because an advertiser does not really know in advance how much exposure it will get with a placement in a given game. Unlike traditional media, most games (except currently-launched MMOs) do not have circulation or viewer numbers. There are possible estimates, particularly with sequels or annual sports games. Still, these are often merely estimates and can vary wildly from the actual sales numbers.

How do both sides protect against this risk? An advertiser may ask for a minimum guarantee of unit sales at a certain time, or a minimum number of impressions for a dynamic advertisement. For instance, a brand may ask that it will pay $300,000 for placement in a certain game so long as that game sells 700,000 units the first six months after launch.

One issue that comes up here is whether or not there is a time set on the game sales. This is important for any brand or game company to know when a sales minimum has been met. Also, the parties should both make certain that the territory is clearly set out in an agreement on the sales guarantee as well as the platform. For example, is this worldwide for all platforms or just the Xbox 360 version in the United States?

It usually makes the most sense to tie the sales minimum directly with the scope of the advertising, meaning if the advertisement is in a game on a certain platform in a territory, those count toward minimal sales.

What if sales targets are not met -- or, for various reasons, the developer decides that the placement would jeopardize sales and thus needs to be minimized or not included at all? If the target is not met, there are two usual ways to make up for not meeting the goal.

First, a refund is possible -- but particularly for game companies, this can be a complicated process. As an advertiser, it is important to include language that entitles the advertiser to a refund -- and if the placement is not included or not correctly included (especially in static placement circumstances), entitles the advertiser to terminate the agreement, receive a refund, and even include a penalty on the game company.

In dynamic short-term placements, the advertiser should consider more general remedies -- such as a "make good", where the advertiser receives additional advertising in other games to make up for the difference. Also, if a static advertisement does not meet SKU sales quotas, then perhaps the advertiser would rather have a certain volume of dynamic advertising in another game.

As a game company, you clearly want to try and avoid including strict remedies, and instead allow flexibility to include a make good as necessary to deal with fluid and changing circumstances during development. One compromise that we have found to work in these agreements is to divide the issue into two categories.

The first would be where the game company determines not to include the placement at all, or a substantial portion of the placement -- in which case, the advertiser is entitled to a refund, but only on a pro-rata basis (meaning the developer still gets a certain amount from the advertiser).

The second would be where only a non-substantial portion or element of the placement is not included -- in which case the advertiser is entitled to more limited remedies. Of course, the parties will have to develop a standard to distinguish between substantial and non-substantial based on the actual placement. Overall, contemplating a "plan B" while drafting the "plan A" agreement is critical to a smooth road if sales/impression targets are not met.

A related contractual issue worth raising here is what happens when an advertiser does receive the placement -- but decides later that it is very unhappy and wants to file for a court order to avoid having the placement go public or force a recall of the game. It is vital for game companies to ensure that there is language in the agreement that eliminates or strictly limits the advertiser's remedies to money damages and precludes the advertiser's ability to file for an injunction to stop production of the game or force a recall.

This is a particularly hot button issue for advertisers who do not usually waive any remedies, particularly one that may bar the advertiser from fully protecting their brands and trademarks. This is an interesting issue as it highlights the unique differences between what is important to the game developer -- which is getting the game into consumers' hands -- and advertisers, who are entering into new territory in games but still have traditional viewpoints on approvals, brands, and contractual remedies.

In view of the differences, we recommend that both advertisers and game companies try and find a common ground on this issue. For example, the advertiser would waive its right to equitable or injunctive relief after advertiser has given final approval over the in game placement so long as such placement and context of such placement remains materially unchanged.

A game company may want to go further to indicate that even if the placement is materially altered, the advertiser's rights are limited to where the alteration is a violation of law or a direct infringement of the rights of a third party.

Massive, Inc., recently issued a press release on a recent Nielsen study. This study revealed that 70% of gamers agreed with the statement that the dynamic in-game advertising made the game appear more realistic, and thereby was effective in promoting brand recognition for advertisers and their target audiences. The study also reported that 82% of gamers surveyed said games were just as enjoyable with in-game advertising.

In some cases, advertising unquestionably improves the game experience. For instance, consider a baseball or racing game without advertising. It would appear so unrealistic to the player that most players would actually enjoy a more immersive and realistic experience that includes advertising.

However, this type of increased player happiness is not the case generally with in-game advertising. In-game advertising has to be appropriately placed in context, and must not interfere with the immersive game experience. By way of example, GameSpot has a yearly award called "Most Despicable Use of In-Game Advertising" reserved for the game that goes much too far with in-game advertising.

As an advertiser or game developer/publisher, it makes sense to consider the appropriateness of any ad placement. The time a user spends with a game and the pervasiveness of games can work against a brand if the advertisement is not appropriate.

The balance here is that advertising works well in certain contexts and not well in others, and in any case the in-game advertising must not interfere with the player experience. In many instances, advertisers and game companies should consider using placements as a potential added benefit to the gamer that does not take away from game playing but is somehow more relevant, such as added benefits to the game player such as additional points or special access to additional parts of the game not seen by others.

Given the discussion above, it is clear that in-game advertising as an industry, and the negotiation of agreements associated with it are in a critical period. Many elements are in flux as advertisers, agencies, and game companies are sorting out their appropriate roles as well as deal terms, pricing, and risk assumption.

Over the next several years, more industry standards will be developed through market forces and longer relationships. For now, the best approach for any party is to be well-informed about the critical elements of each negotiation, including possible variations on certain deal terms, your party's interests, and the risks associated with the deal as well as of course, whether or not the placement is beneficial to the advertiser, game company, and the players.

[S. Gregory Boyd and Vejay G. Lalla are attorneys in the Advertising, Marketing and Promotions practice group of Davis & Gilbert LLP. Please email the authors at [email protected] or [email protected] with questions about this article.]

And Now, A Game from Our Sponsor, The Economist, Technology Quarterly, June 11, 2005.

Bachman, Katy, Nielsen, Activision Announces In-Game Ad Test, Mediaweek, October 18, 2004.

Grimes, Sara, Kids' Ad Play: Regulating Children's' Advergames in the Converging Media Context, 12 International Journal of Communications Law & Policy, 161, Winter 2008.

Grossman, Seth, Grant Theft Oreo: The Constitutionality of Advergaming Regulation, 115 Yale L.J. 227, October 2005.

Ives, Nat, Teen Mags? So Five Years Ago; Advertisers Enamored with Web, Niche Channels, Advertising Age, July 31, 2006.

Klaassen, Abbey, Game-Ad Boom Looms As Sony Opens Up PS3, Advertising Age, February 25, 2008.

Klaassen Abbey, Buying In-Game Ads? Be Sure They're At Eye Level; Study: When Trying to Attract Players' Attention Bigger Isn't Always Better, Advertising Age, July 23, 2007.

Lesson to Take Away; What Marketers Can Learn From Games, Advertising Age, May 19, 2008.

Nelson, Michelle et. al., Advertainment or Adcreep Game Players' Attitudes toward Advertsing and Product Placements in Computer Games, Journal of Interactive Advertising, Vol. 5, No 1 Fall 2004.

Oser, Kris, Julie Shumaker; National Director of Sales-Video Game Advertising, Electronic Arts, May 30, 2005.

Sullivan, Laurie, Beyond In-Game Ads: Nissan Takes Growing Market To Different Level, Advertising Age, June 18, 2007.

Lessons to Take Away: What Markets can Learn From Video Games, Advertising Age, May 19, 2008.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like