Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

A recently-leaked employee handbook reveals that at Valve, trust in employees runs absolutely rampant. Gamasutra editor-in-chief Kris Graft examines the handbook and the flat management structure.

There's a certain employee handbook [PDF] making internet rounds, one that portrays a completely idealistic, pie-in-the sky way of doing business that could never work at a mid-size developer, especially one that generates billions of dollars of revenue in the real-life video game industry.

...Well, that's what you might think if this wasn't the new-hire handbook of Half-Life house Valve Software, which has been putting the concepts and principles described within into practice since 1996. And if you didn't hear, Valve is a pretty successful company.

So when a sneak peek into the culture of Valve comes sliding under the door in the form of this handbook -- which Valve confirmed to Gamasutra to be authentic -- video game makers both big and small had best take note.

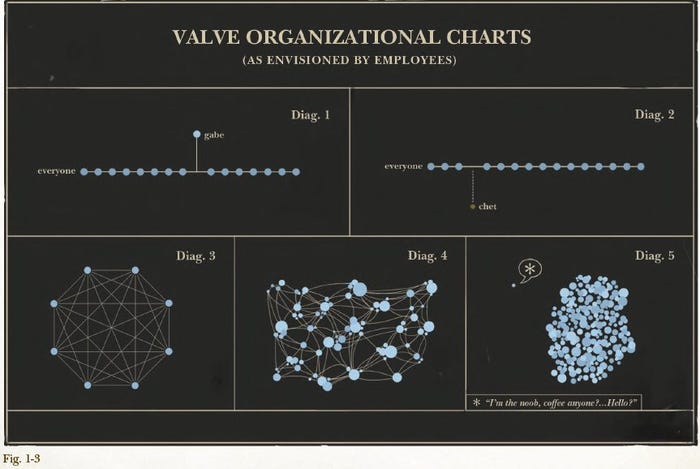

The most striking aspect of Valve's handbook -- and the recurring theme that gets so many wanna-be Valve staffers salivating -- is the amount of freedom and independence that the company grants its employees through a flat management structure.

New hires aren't plopped onto a project by middle managers. Rather, they individually choose what project they want to work on. Allowing trust and empowerment to run so rampant sounds like pure management insanity, but it seems that this model allows for the best projects to organically rise to the surface, when the right people are in place.

Flat management structures aren't unheard of -- they're quite common with startups -- but Valve has maintained and scaled this structure from its launch as a startup to today's 290-person, independently-funded game industry powerhouse that generates billions of dollars a year. That makes this approach rather uncommon.

Judging by the handbook, the way that Valve became known for its great games and hugely-successful Steam platform apparently wasn't through mighty Valve boss Gabe Newell cracking his whip across the backs of his employees, but by creating an environment of trust and accountability.

"Hierarchy is great for maintaining predictability and repeatability. It simplifies planning and makes it easier to control a large group of people from the top down, which is why military organizations rely on it so heavily," the handbook reads.

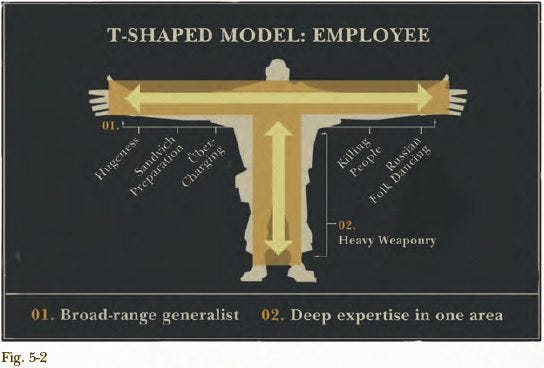

"But when you're an entertainment company that's spent the last decade going out of its way to recruit the most intelligent, innovative, talented people on Earth, telling them to sit at a desk and do what they're told obliterates 99 percent of their value," it continues. "We want innovators, and that means maintaining an environment where they'll flourish. That's why Valve is flat."

Valve sides with personal growth rather than organizational advancement, which is a bit reminiscent of the game design debate of intrinsic vs. extrinsic rewards. Will people benefit more in their career through learning and working in a flat multidisciplinary structure, or by advancing to the highest possible box on the organizational chart? The answers to each are not mutually exclusive, and there's a legitimate argument for both, but Valve chooses the former approach.

The key to such a flat structure at Valve is the hiring process, and the company pulls no punches in stressing the importance of recruitment, which Valve encourages everyone to take part in.

"Hiring well is the most important thing in the universe," the handbook reads. "Nothing else comes close. It's more important than breathing. So when you're working on hiring -- participating in an interview loop or innovating in the general area of recruiting -- everything else you could be doing is stupid and should be ignored!"

That's a fairly straightforward message.

To me, the lesson here is less about structure (though it's fascinating to hear more about how things work at Valve), and more about working with people whom you trust. By all means do not immediately go and flatten your studio or team structure after reading this. Valve was founded from the get-go to work this way, and surely if certain companies tried to remove a structure of direct reports and middle managers, they could very well collapse.

But no matter what structure, there's something to be said about trusting the people you work with, and maybe you will come to (or have already come to) a point where you need to seriously ask yourself if you trust the people you work with.

Trust is valuable: it can translate to a more reasonable work/life balance, a greater sense of empowerment, better efficiency, greater creativity, and an immense sense of satisfaction for a job well-done. In the end, what else would you want from a career in making games? Or really, a career doing anything?

Okay... maybe more money. And in Valve's world, trust and empowerment actually have translated to fatter bank accounts for its employees -- those idealistic, pie-in-the-sky-eating Valve employees.

(Thanks Flamehaus for making the handbook public.)

This article was originally published in 2012. It has been lightly updated for formatting in 2023.

You May Also Like