Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

As a follow-up to project specific financing options, we now turn to the wonderful world of company-based equity funding, where investors are betting on your ability to grow the value of your studio long-term.

A version of this article was first posted to the Canadian Media Fund's Trends online magazine and analysis website, and is in part derived from the Funding What When lecture at GDC 2018's Indie Game Summit.

While publishers have been funding games since the dawn of the video game industry, more traditional business angel and venture capitalist communities are relatively new to the game industry investment table. Stories keep popping up about studios receiving millions of dollars of funding from VCs. Sometimes a lot of money, like the recent US$1.25 billion investment into Epic Games!

And so, when game developers embark on their money-hunting quest, they often include VCs and angels on the hit list. But, critically, VCs and angels are part of a broader category of investors that fund at the company level. They do NOT invest in projects like a publisher normally would. This means that company level investors are taking equity in your studio (i.e., they are buying shares), and thus become a longer-term partner in your studio.

That said, when you take on an equity investor, it doesn’t mean you are losing control of your company. While an investor does gain certain rights, and has voting power relative to their number of shares, they are usually investing in the leadership and have no interest in taking over. Still, properly negotiating your shareholders’ agreement is one of the most important things you’ll do for the long-term health of your business.

As a co-owner of your studio’s shares, equity investors care most about increasing the value of those shares over time. Yes, they want to back an inspiring founding team. Yes, they want to help you change the world. Yes, they want to see you succeed in creating something innovative and groundbreaking. But, all of that is in service of generating a meaningful return on their investment, which only happens when they sell the shares at a much higher price than they invested at.

Generally speaking, equity level investors want to back companies that have the potential to scale massively, and deliver exponential growth. It is just the way their math works, when you consider that most investors build a portfolio of companies, and that most of those companies are likely to fail. Then the one or two that do succeed need to succeed so greatly that they overcome the rest of the losses.

It is critical to understand that if you are not working on projects that are massively scalable or within a business model that can deliver exponential growth, then you are absolutely wasting your time talking to company level investors. This doesn’t necessarily mean you can only do free-to-play / games-as-a-service games, but that’s most typical in today’s market.

Equity funding is not better than project funding, or vice versa. They are simply different forms of funding best suited for different kinds of opportunities. Refer to the previous article on game project funding for more details on that aspect of fundraising.

Now, assuming you do in fact have a scalable opportunity, here are the common sources of company level funding:

Sweat Equity

You and your cofounders are always the first investors in the company. Often not with actual cash, but with under/uncompensated time, effort, expertise, contacts, etc. (aka your blood, sweat, and tears). This is also how cofounders generally earn their initial portion of shares in the company.

Friends, Family & Fools

This category is also often referred to as “love money”, in that only someone who loves you would be foolish enough to invest in your company. There is a fine balance in your confidence of success versus risking the savings of loved ones, though later investors often take this as a positive signal.

Accelerators & Incubators

There are hundreds of accelerators and incubators across the globe offering to mentor your startup, provide entrepreneurial coaching, connect you to key partners, and ideally provide some funding as well. Sadly, very few of them will touch game studios, or have the right expertise/network to be relevant. Tread carefully.

Equity Crowdfunding

Less common than the normal “rewards” based crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter and Indiegogo, equity crowdfunding offers an actual slice of your business. Since this is a means to solicit investment in highly risky endeavors, equity crowdfunding is heavily regulated and not necessarily legal in all countries.

Angels

Angels are wealthy individuals who are investing their personal money. Generally they want to feel like they can provide more value/wisdom than just writing a check, and thus often invest in the industries where they already have had success (along with expertise, connections, etc., that they can share). Angels are often hard to find, and usually do not “reveal” themselves or have a website. In some cases, they may belong to an angel network/group organized on a city or regional basis, making it slightly easier to find them. Alas, it often requires deep personal connections and non-stop hustling to find suitable angels.

Venture Capitalists (VCs)

VCs are professional investors and fund managers. Unlike angels that are investing their personal wealth, VCs are aggregating much larger investors (called “limited partners,” or “LPs”) into funds and then investing on their behalf. Famously, many VC firms are located in Silicon Valley, but you can find VCs across the globe. These are generally well-run firms, with professional staff. They have websites, and often attend pitch and startup events. The challenge for game developers is that many VCs tend not to invest in the game industry, as they deem it too risky and are not familiar with the operational complexities of running a successful game studio.

Corporate Venture Funds

Also referred to as strategic investors, large corporations often manage an internal investment fund that allows them to invest in interesting/innovative companies that are relevant to their business. While making sound financial decisions is still critical, the priority of doing a deal is more weighted toward the potential strategic value. An example would be if Intel’s corporate venture fund invested in a startup making advances in quantum computing. Many large publishers, especially from Asia, have taken an aggressive approach to strategic venture investing, beyond normal publishing deals.

Technically, an initial public offering (IPO) is also a form of selling your equity via a public stock market (e.g., the NASDAQ). But, IPOs generally come much later after demonstrable success, and are beyond the scope of this article.

An important nuance to keep in mind is that not all equity investors are actually buying equity from the outset. Often for smaller/earlier investments, deals are done via a convertible note instrument. Essentially, this is a loan that is repaid in equity when it matures. It sounds more complicated than it is. The main benefit is that it allows you to take in funding early, when it is hard to place a tangible value/price on your shares.

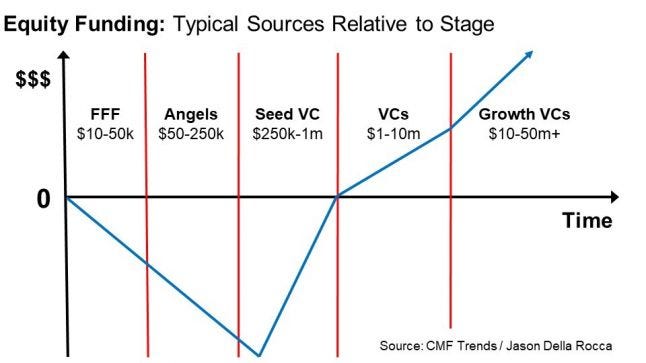

Now that we know the typical categories of equity funding, we need to consider the ideal timing of each source relative to the stage of your company. Sadly, we can’t just collect a big bag full of money whenever we want to. Understanding the sweet spot for each source is critical.

The above graph follows a hypothetical game studio’s lifecycle, plotting its revenues over time along the blue line. At the start, the blue line goes negative given the studio is burning cash on development and not initially generating any revenue. Then as the blue line heads upwards, revenues are coming in and eventually crosses the break-even line (i.e., the horizontal axis) and starts generating profits. The timing on this cycle is highly variable, depending on size of the team, scale of production, business model, platform, etc. Meaning, it could all take place in a matter of weeks if you made the next Flappy Bird-style success over the weekend. Or it could be a multi-year cycle if you are working on the next big MMO.

As you are getting started, generally love money is the only viable option. These are relatively small amounts of funds to help you get started, and enable you to advance the project/business far enough to convince angels to invest. Angels rarely invest in ideas alone and demand something more tangible (e.g., a prototype or MVP, or some other form of initial traction).

Angels are able to invest slightly larger amounts of money, and importantly provide wisdom to advance your business. Ideally, they are also connected to seed VCs and can help with this stage of fundraising. With the progress made and traction gained with your angel money, then you can approach early stage seed VCs for funding.

Importantly, these three categories of investors (FFF, angels, and seed VCs) are all coming in before you’ve proven that you can generate profits. This means they are taking a bigger risk, generally banking on the vision of the business and pedigree of the team. This is also the timeframe when incubators and accelerators come into play (i.e., pre-profit). While each program is highly variable, their sweet spot seems to be some time between friends & family and angels.

Finally, once the company has proven it can generate profits consistently, then normal VCs can be approached to fuel this initial success, with much larger growth stage VCs coming in to fuel massive growth during elevated phases of profitability.

Now, despite all of those “typical” scenarios, anything is possible when you have certain unfair advantages, like your spouse just won the lottery, or Fortnite’s creative director spins out to start a new studio. If that’s not you, then heed the typical timings outlined above.

Keep in mind that as the funding amounts increase at later stages (in some cases, into the tens or hundreds of millions), more has been proven/validated about the business. Thus later stage investors writing bigger checks are taking on less risk and uncertainty. In fact, it is your friends and family that write you a small check for a few thousand dollars in a context of high uncertainty that are actually taking the biggest risk, and are least likely to see a return on their investment.

Further, as a rule of thumb, the smaller the check, the “closer” the investor is to you both relationship-wise and geographically. Friends and family, well, they are potentially in the same home as you. Critically, angel investors prefer to invest where they live. First, so they can be more involved, attend board meetings, go for coffee with the founders, test the prototype, etc. (without the cost/time burden of getting on a plane). Second, doing cross-border investing can become extremely costly (e.g., extra legal/tax advice, document translations, etc.) that could outpace the actual amount invested. As the deals get into the growth stages, the world opens up.

If you are still in the earlier pre-profit stages of your company, look “closer” for investors. Be warned: jumping on a plane to fly across the globe to angel and VC hotbeds like Silicon Valley or Tel Aviv will most likely result in “nice, but come back when you are more advanced” style responses.

Fundraising for your company is rarely a one-shot deal. Few investors are willing to bankroll your entire budget based on an initial pitch. Rather, fundraising is an ongoing process (sometimes never ending) of pitching, closing a round of funds, and using those funds to gain traction/make progress. Then, that progress allows you to improve the story, and go back out and pitch/raise/progress all over again. Then...profits.

In that sense, a good metaphor for fundraising is the rally race, going from checkpoint to checkpoint, filling up with enough fuel and resources to survive until the next checkpoint, where fans and partners are waiting (hoping!) for you to arrive to fuel up again. All along, you’re checking the map and navigating around obstacles based on constantly updating conditions.

Luckily we are not alone in this race, and many have navigated it before us, though perhaps less so on gaming soil. Still, there are countless resources, videos, events and blog posts from the startup world to get you rolling. None are more suitable than Guy Kawasaki’s Art of the Start, or Brad Feld’s Venture Deals.

See you at the finish line!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like