Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

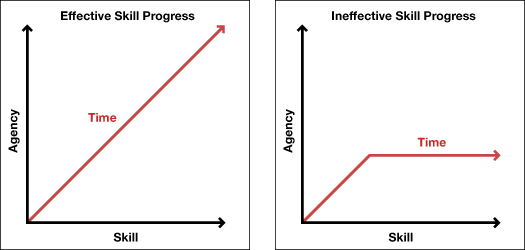

A look at player investment and progression as generated by the relationship between skill and agency.

Mr. Isigan posted an interesting article yesterday about stagnating plots affecting the player’s sense of progression (my thanks, Mr. Isigan, for providing a good read and a topic of discussion). He mentioned two axes of experience in that article: plot and time. In this post I would like to point out and further analyze the other crucial axis to the experience of progression (aforementioned by Mr. Bycer) which Mr. Isigan somewhat neglected: skill.

The Hypothetical

Let’s take a look at that hypothetical example he gave concerning a serial killer as an illustration of stagnating plot which destroys the feeling of progression:

"An ill-minded man with a butcher knife in his hand secretly enters the bathroom of a young woman which, unaware of all this, is taking a shower. With a sudden move the man opens the shower curtain and frantically stabs the young woman to death. Just as he’s finished, he realizes that a neighbor, an old prostitute, has witnessed the scene. He immediately goes to the neighboring home and kills her. Just as he’s finished, he realizes that another neighbor, a middle-aged nun, has witnessed the scene. He immediately goes to the neighboring home and kills her. Just as he’s finished, he realizes that another neighbor, a young cheerleader, has witnessed the scene. He immediately goes to the neighboring home and kills her. Just as he’s finished, he realizes that another neighbor, an old cleaning lady, has witnessed the scene. He immediately goes to the neighboring home and kills her."

I would have to agree that such a situation is patently absurd. And yet, one wonders whether the inability of the game to harness the ridiculousness of the situation itself is what would cause a detriment to the experience, and not actually the repetitiveness and horizontal non-development of plot. Let’s consider the above scenario seriously; how can we make this into a viable experience? Such an exercise would help establish that a game can have progress even when the plot is purportedly stagnant.

Unstated Assumptions

An initial question: how deep would the “pure action” (as worded by Mr. Isigan) be in this game (or how much skill is there to be learned and how much does that skill level impact player agency)? If it is a simple matter of just running over to the victim and pressing a button without any challenge at all, that would actually fail in any game pretty much regardless of how amazing a plot has been applied.

Actually this assumption of a lack of challenge is really the greatest hurdle as well as the greatest boon in implementing the above into a feasible game experience. The severity of the actions of the player vis-à-vis the implicit assumption of the wildly disproportionate helplessness of the victims destroys any chance for credible suspension of disbelief. But if we destroy this to begin through the use of a highly satirical tone (we can satirize the player’s assumptions that the [conspicuously exclusively female] victims are helpless, for instance), the primary problem disappears.

Say, the old prostitute is actually an undercover vice cop; the middle-aged nun is a recovering former assassin; the young cheerleader turns out to be a supremely fit killing machine; the old cleaning lady wields a volatile cocktail of toxic household cleaners and knows the ins and outs of the building like the back of her hand; etc. These “victims” would each provide their own unique set of challenges and cause the player to develop/exercise considerable skill.

Admittedly, the suspension of disbelief (if you could call it that) in such a game would rely heavily on the efficacy of the satire/writing. But at any rate, if the game mechanics were compelling and deep enough, the player would become invested in developing his skills in negotiating them despite a redundant (in every sense of that word) plot.

That is to say, the other assumption in the hypothetical case above is that the feeling of progression relies almost solely on plot, which is not necessarily true in games. There is no doubt that good writing and plot pacing contribute mightily to the player experience (and would, in this case, make the difference between thoughtful feminist critique of male power fantasies in core games and slasher flicks, or irredeemable and actually misogynistic camp). But the point is that suspension of disbelief which arises from a properly developing plot is, in fact, not entirely necessary when player investment and progression is created largely through skill development.

Counter-Strike, for instance (a game Mr. Isigan mentioned as containing “climbing tension”), has absolutely no plot progression to speak of (this is not to say it doesn't have a "narrative"). It’s the same story of disarming/planting the same bomb at the same bomb site, or rescuing/preventing rescue of the same hostages from the same locations over and over, round after round. Condensed in this manner, CS is really no less redundant, and actually no less absurd, than his example of the serial killer who kills one victim after another. It is simply that CS provides a high level of complexity and a large number of opportunities for variations (and thus improvements) in the execution of these same, repetitive ludic goals.

Examples of Skill Axis Based Progression

Recently, I’ve been burning a lot of hours playing King’s Bounty: Armored Princess. It’s a rather terribly written (or perhaps in this case poorly translated) game—so much so that its metascore would probably be several points higher were it not for how painful it is (again, no contest on the idea that bad writing can be damaging to the player experience). Even further, the game mechanics and events are entirely repetitive.

In other words, if KB:AP was considered only along the two axes of plot and time, it’s a game that could be called an utter failure. And yet the game has a highly compelling sense of progression. It’s an addictiveness which arises from the depth of skill involved and the manner in which the game continues to reward the development of skill by granting further agency along the full length of its skill development path.

Compare this with EA2D’s flash game Dragon Age: Journeys, whose gameplay is quite similar, but which fails to achieve the same level of player investment. The writing isn’t nearly as bad as KB:AP, and yet it’s tactical depth is weak enough to induce boredom in far less time. That is, player investment dries up quickly because the “skill axis” plateaus too fast and the amount of agency to be gained in the game is too shallow. Indeed, any investment which arises at all is really in unlocking those items for use in the “real” game, Dragon Age: Origins.

Perhaps a more useful example is taxi driving in GTA3. This example is basically exactly the same as the serial killer hypothetical situation: you pick up a customer, you drop them off, one after the other. The mechanics never change and there’s no plot whatsoever. What does change, though, is the expertise of the player in driving a car, the speed at which a player can reach the same handful of destinations, and the developing knowledge of the map which allows the player to reach these locations even faster. Not only is the player learning how to drive and navigate the map better (essential skills to the game), he’s getting paid to do it. And the more skilled the player is at the job, the more he gets paid.

Doing Skill Axis Based Progression Right

The important thing to take away from these examples, then, is that for the player to experience progress (at least, in games where plot is trivial), increasing player skill should have a direct, proportionate, and continuous correlate in increasing player agency with respect to an equally proportional challenge, and the amount of player skill which can be developed should not be trivial.

Skill versus Agency

Skill versus Agency Continued

Which is to say, the examples Mr. Isigan describes of “pure action” failing to generate “climbing tension” have more to do with skill axis stagnation than plot axis stagnation. These are situations in which a player’s level of skill has little to no impact on his agency (“skill caps,” if you will) due to restrictions mandated by the developer (the primacy of items over skills in WoW or the obligatory time sink of skill learning in EVE Online come to mind). Such experiences often “[feel] fake or arbitrary or biased towards the business model,” but the feeling in these cases arises from "artificial" limitations on the player’s capacity to affect the game mechanics than from poor narrative design.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like