Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Nintendo Magic: Winning the Video Game Wars is a new book from Nikkei reporter Osamu Inoue, who spent three years researching the company, and in this excerpt covers the biographies of president Satoru Iwata and chief designer Shigeru Miyamoto.

May 14, 2010

Author: by Osamu Inoue

[Gamasutra is pleased to present an excerpt from Nintendo Magic: Winning the Video Game Wars, a new book by Nihon Keizai Shimbun reporter Osamu Inoue which provides a fresh window into the company that's risen to new heights of success with the Wii and DS. The book is out now in the U.S. via book publisher Vertical.]

"On my business card, I'm a company president... But my mind's that of a game developer... And at heart, I am a gamer." - Iwata

"Sending text messages is way more fun for them than any game we make. If we made a game where you have to type a certain message as fast as possible and competed nationwide, that'd probably be the most fun game in Japan." - Miyamoto

On June 27, 2008, at 10 AM, over 500 shareholders were assembled at Nintendo corporate headquarters in Kyoto, Japan. They had come to the white, fortress-like building to participate in the shareholders' meeting for the 2007 fiscal year.

The assembled shareholders first heard a short audit report from the auditor, then Iwata began his business presentation. Sales, operating profit, net profit -- all were at record highs. The Wii had contributed significantly. Their DS business was running on all cylinders, and the number of game titles that had sold a million copies or more had doubled from the previous year and were now up to 57.

There was nothing to complain about. Yet Iwata stood there solemnly, and during the question-and-answer session, he said, "There's an inherent risk of complacency setting in. As a result of our customers' support we've been blessed with a tailwind, but people in the company are going to start taking it for granted. I'm trying to figure out how to nip that in the bud."

No matter how long their success might continue, Iwata wanted to keep the company both hungry and humble.

When he assumed the presidency of Nintendo, his strategy was to try to increase the gaming population. The plan brought Nintendo explosive profits over a very short period of time. This success was derived from basic economic principles, and it's easy to see Iwata as a brilliant strategist, in this light.

Nintendo's traditional marketplace was a proverbial sea of blood -- Iwata realized there was no future in fighting a war for the territory Microsoft and Sony were determined to claim, and instead set a course for less troubled waters -- that is to say, people who don't play video games. Therein lay their success, or so the analysis goes.

But Iwata says this: "It would be cool if I could say 'Yeah, I knew it all along!' about what's happening now, but that's just not true. Even though I had confidence that our direction was the right one, the truth is I had no idea things were going to happen the way they did, as quickly as they did. On the contrary, it made me think, wow, when things change, they sure change fast. I still can't be sure what it is that will make people react strongly to what we do."

Iwata can say this with a straight face because rather than working for results, he'd done what he thought was right; the results had followed.

The right thing to do was to stop players from deserting games, and to bring videogames to a wider audience. To do that, they had to honestly engage the question: How do we make a console that won't be considered a nuisance, and how do we make a console that has something to offer everyone in the family?

Even though the path they'd chosen had won the approval of the marketplace and exceeded all expectations, they could not afford to become self-satisfied or change their strategy. To put it another way, they couldn't get cocky.

For example, the Wii represented the first piece of fully internet-capable business infrastructure Nintendo had sold, and it opened up two possible revenue streams. One was Wii Channels.

The Wii Channels -- with the ability to display up to 48 different services, from news and weather reports to television schedules -- was more internet portal than game console.

By the end of 2008, Wii sales in Japan totaled some 7.8 million units. About 40 percent of those were connected to the internet. With 3.1 million units online, we could call the Wii the biggest TV portal in Japan. Looking abroad, that number rose to 18 million units. It was surely the single most successful TV-based portal service in the world.

As people flocked to it, the value of the platform rose. It was natural that other companies would become interested in providing content for the Wii Channels, even if it meant sharing revenue with Nintendo. Fujifilm was one such company -- the first to maintain an independent channel on the Wii.

The Digicam Print Channel, added in July 2008, allows users to upload photos stored on an SD card and order prints directly from Fujifilm. It wasn't just prints -- the service included a variety of Nintendo-like touches, allowing users to purchase whole albums of their photos decorated with images from games like the Super Mario series, or order business cards with their Mii avatars.

There were other companies that want to use this new infrastructure for online transactions.

"Moms would like it if they could get information on the sales at the local supermarket." "It'd be great for the family if they could order in-season produce from other regions."

Retail giant Seven & I Holdings, online shopping mall Rakuten, and others -- they have all taken interest in the Wii Channel, and the possibilities seem endless. In addition to the usage fees Nintendo can collect, hidden within the Wii is the potential for staggering advertising revenue.

However, when confronted with such possibilities, Iwata's reaction was not what you'd expect.

"I think that calling the Wii Channel a new revenue stream smacks of counting the chickens before they've hatched, and anyway -- that's not why we created it. It might turn out to be something besides a game that brings in money for the company, but that's all."

In the end, the Wii Channel was created to answer the questions "How can the Wii offer something to everyone in the family?" and "How can we get someone to turn it on every day?" Iwata says that using it as a source of revenue is purely secondary.

"We think there's a tendency in internet businesses to give daydreams and visions too much priority. People should wait until their site actually starts getting 30 million viewers worldwide every day before thinking about how to monetize."

What opportunities for revenue on the Wii channel might Nintendo itself develop for its main business? Iwata's position remained steady on the issue even regarding the Virtual Console, a game download service for the Wii.

The Virtual Console allows users to download games originally published for older consoles like the NES and 64. The games are cheap -- between 500 and 1,000 yen. In late 2007, roughly a year after the launch of the Wii, the Virtual Console had sold roughly 7.8 million games, bringing in revenue of 3.5 billion yen. It doubled that figure in just three more months, as game assets that had been long unused again saw the light of day.

Yet even the Virtual Console was developed not for "revenues," but as part of Nintendo's efforts to answer the question: "Why do video game systems get treated as unwanted guests?"

Up until the Wii, none of Nintendo's home consoles had been backwards compatible; if you wanted to play an old game, you had to keep the old console, and Mom couldn't stand seeing all those videogame systems lined up by the TV. But what if getting a Wii meant all those old machines could be put away? Thus was the Virtual Console born.

Near the beginning of the Wii's development, Iwata said to [Nintendo R&D general manager Genyo] Takeda -- and it wasn't clear if he was joking or not -- "What if we made a console with like six slots, so you could play games from all kinds of systems?"

Takeda later agonized over this in private. Did the president mean it?

The truth was somewhere in between: "The thought was serious, but I was half-joking about the method," Iwata says. Eventually they settled on a virtual solution where games from a variety of older systems could be downloaded via the internet.

It was not unlike the "Famicom Mini," which reissued old NES games. They went on sale in 2004, winning success by including games that hearkened back to the NES era, appealing to both the nostalgia of adults who'd played the games as children and the frustration of those who hadn't been allowed to.

Perhaps nostalgia could be another aspect of the new game system. That possibility was the basis for the development of the Virtual Console. "We don't want to just give the games away," says Iwata flatly, "but it also isn't meant to pull in huge revenues."

At the same time, he's confident he'll get good results. "There's always the possibility that it could become an unexpectedly large revenue stream. It involves so much less energy than making a new game. I have confidence that they'll be more steadily profitable than the cell phone games a lot of game developers are working on now."

What kind of man is Satoru Iwata -- that he can perfectly balance humility against unwavering confidence? A closer look is in order.

The Wii -- which at the time was still known only by its codename, "Revolution" -- was revealed at E3 2005, though the design of its controller would remain a secret.

Two months before that, Iwata was at the Game Developers Conference (GDC) in San Francisco. On the fourth day of the event, he took the stage after Microsoft's vice president and delivered his keynote address. He began by holding his business card up in the air.

"On my business card, I'm a company president," he began. Then he pointed to his head. "But my mind's that of a game developer." Finally, he put his hand to his chest. "And at heart, I am a gamer."

This self-introduction perfectly captured the essence of the man named Satoru Iwata, and it won the hearts of the audience in an instant.

No matter how far back we look in order to understand Iwata -- who dedicated himself to broadening the gaming population, succeeded, and yet remained humble -- we will find games.

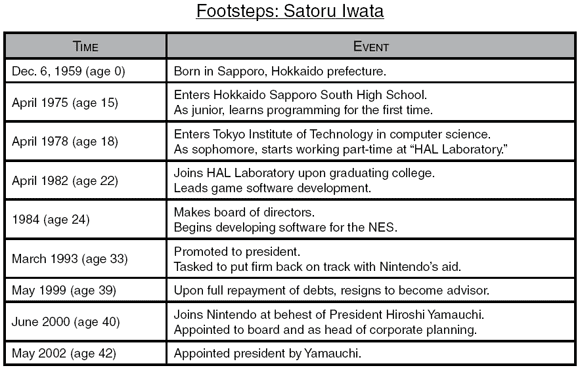

He was born in Sapporo, on the northern island of Hokkaido, in December 1959. The eldest son of a prefectural official, he was brought up comfortably. He displayed leadership potential early, serving variously as class president, student council president, and club president while in middle and high school. It was while attending Sapporo South High School that he first encountered computers.

It was regarded as the best school in the city, having turned out many graduates who went on to become well-known political and business figures. The school philosophy emphasized initiative and autonomy -- it lacked even a uniform, making it a rarity among Japanese high schools. Iwata had a part-time job washing dishes, and with the money he saved up (along with some extra from his father) he bought a Hewlett-Packard HP-65 calculator.

It was the world's first programmable calculator. Introduced in 1974, it was considered a marvel of engineering, having even gone into space as a backup for the Apollo Guidance Computer during the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project.

The word "PC" hadn't even been invented yet, but already Iwata was drawn into learning how to program the tiny computer, devising games like "Volleyball" and "Missile Attack" and playing them with his classmates.

In love with computers, Iwata entered the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 1978 to study computer science. This time he used the money he received as a graduation present to buy a Commodore PET -- with integrated monochrome display, keyboard, and cassette tape reader, it was the world's first all-in-one computer.

He would store his programs on cassettes, and bring them every week to the Seibu department store's computer department to show off. By the time he was a sophomore, a group of the store's employees had formed a company called HAL Laboratory -- and they invited Iwata to join them. It was the beginning of his career as a game designer.

The computer that appeared in Stanley Kubrick's film 2001, "HAL," turns into "IBM" if you substitute each letter with the one that follows it in the alphabet. HAL Laboratory took their name as an homage to this -- it indicated their resolve to "stay one step ahead of IBM."

It was a lofty name, but when the company was founded it had only a handful of employees who worked out of a one-room apartment in the Akihabara district of Tokyo. Its main business at the time was the development and sales of peripherals for the PCs (then called "microcomputers") that were becoming popular at the time. They had only one game programmer -- Iwata, the part-timer.

Just as he was starting the job, his father, Hiroshi Iwata, won the mayoral election for the city of Muroran. In the four terms he served thereafter, he left behind him a legacy of achievement on behalf of the city, including fighting for fiscal reform, pushing through construction of the Hakucho, or Swan Bridge (which straddles the Port of Muroran and is the largest suspension bridge in eastern Japan), and preserving a Nippon Steel Corporation blast furnace that was scheduled for closure.

Iwata was now the son of a mayor. He was attending a top school. But he had no interest in becoming one of the elite. He was so fascinated by games that upon graduation, he went straight to work for the unknown HAL. As the company's first video game developer, he had no one there to learn from but continued to polish his skills on microcomputer games on his own.

The shock came in the second year of the company's operation, 1983. Nintendo unveiled their game-oriented computer, the NES (or "Famicom" as it was known in Japan). It sold for the devastatingly low price of 15,000 yen.

"Please let me write games for it."

Iwata's feet naturally took him to the company's headquarters in Kyoto. It was the beginning of a beautiful relationship.

At the time, game programmers like Iwata were still quite rare. For Nintendo, whose internal software development system was not yet sorted out, his sudden appearance was a godsend.

Golf, Pinball, F1 Race... HAL Laboratory successfully undertook software development for Nintendo to publish legendary games that supported the NES in its early days -- and by doing so, the smaller company earned the larger one's trust. In 1984, Nintendo invested in HAL, underscoring HAL's importance as a crucial second-party developer.

HAL grew steadily, one employee at a time, gradually expanding the scale of its business. In addition to developing several titles for Nintendo to release under their own name, their peripherals for the NES -- including controllers with autofire capability -- were a hit, and they quickly became a known name in gaming. As Iwata took on more managerial responsibilities, his title changed -- to board member.

But in 1992, despite its rapid growth, HAL Laboratory was faced with a crisis. They filed for bankruptcy protection under the Civil Rehabilitation Act, and were functionally insolvent.

The previous year, having grown to employ nearly 90 people, the company had moved from Tokyo to Yamanashi in an attempt to strengthen the software development section. However, it was just then that the economic bubble burst. They had borrowed most of the money to fund the new location's construction, and compounded with a recent lack of hits and the difficulty of raising short-term funding, declaring bankruptcy was the only option.

It was Nintendo that came to the rescue and supported continuing development.

Yamauchi, then president of Nintendo, had a high regard for HAL's development skills and attached a condition to Nintendo's aid: Iwata would become president of HAL upon the company's restructuring.

It was Iwata's first stint as the manager of a business -- so far he'd been immersed in game creation. Though the company's outstanding liabilities had been lessened, they still owed 1.5 billion yen. Part of that debt would become Iwata's personal responsibility if the company were unable to repay it. But because his thirst to make great games had not been quenched, he trod that thorny path.

In Iwata's own words:

"I feel there's a depth, a wonder to the act of making games. Creating a single game involves constant trial and error, integrating control and play while remaining true to your theme, your concept. You wade through the vast possibilities, converging on a product. I really don't think there's anything else quite like it."

To Iwata, game design was a quest for truth. That truth could be found at the end of a long, hard development process akin to spiritual training. The endless depth of that progression captivated Iwata. Ever since high school, he had loved games more than anyone else he knew, and his desire to create them had led him here.

So despite the path of thorns -- despite the great risk -- Iwata had no choice but to try to turn HAL around. Once he became president, Iwata's almost simple-minded passion for creating games led to two hits for the company: 1992's Kirby's Dream Land, a Game Boy game, and 1999's Super Smash Bros. for the 64. Both were released as Nintendo games, but HAL Laboratory had developed them behind the scenes, with Iwata occasionally writing code himself to finish them.

Kirby's Dream Land was an action game featuring Kirby, a pink balloon-like creature. He could inhale enemies and items like a vacuum cleaner, then spit them back out as an attack. The new style of gameplay helped it sell five million copies, HAL's biggest hit at the time.

Nintendo and HAL would go on to produce a whopping eight more titles over the next six years, including Kirby's Adventure for the NES, which popularized the hero into one that stood shoulder-toshoulder with the likes of Mario and Pokémon. The series has sold over 20 million copies worldwide.

Super Smash Bros. sold 2 million copies, the second best outing for the 64. It's a fighting game, a genre which generally involves two characters attacking each other with punches, kicks, and weapons to bring the opponent's health to zero.

But in Smash Bros., the object was simply to knock your opponent out of the battle area -- and battles weren't necessarily one-on-one. There might be several characters in the ring at a time -- characters from other games, like Mario, Donkey Kong, and Kirby. A new genre had been born.

By making hits out of these eccentric titles, HAL had paid back its 1.5 billion yen debt in just six years, and Iwata had turned the company around.

"Thanks to your help, we've been able to recover," said Iwata to Nintendo president Yamauchi during a visit to Nintendo.

"Will you come work for us?" was Yamauchi's reply to Iwata, who'd gained experience as a business manager. It was a difficult time; Sony was pressing in. This would be a new quest. Iwata felt it was time to return the favor Nintendo had done him, and immediately agreed.

There was another reason for his ready agreement -- Iwata was only too happy for a chance to work side-by-side with a game developer he respected deeply: Shigeru Miyamoto.

He's nominated every year for Time magazine's "100 Most Influential People" list. In 2007 he and then-Toyota president Katsuaki Watanabe were the only two Japanese people on it. In 2008 he was selected in a reader poll on Time's website as the most influential person, pulling in almost two million votes in the process. He is world-famous.

He is Shigeru Miyamoto, Nintendo's senior executive.

Miyamoto's fame, surprisingly, started in America, and is more widespread abroad than it is in Japan.

It started with the arcade game craze, when the kids were all playing a game called Donkey Kong, and continued with a character by the name of Mario, whose history now spans more than 20 years. Miyamoto's work has since garnered him worldwide fame and recognition; he has received countless awards.

For example, in 2006 he was awarded the distinction of chevalier in the French Légion d' honneur, an order originally established by Napoleon Bonaparte. In 2007 British magazine The Economist gave him their Innovation Award in the category of consumer products. The list goes on and on.

Iwata held Miyamoto in the highest regard, and as a fellow game creator, set his sights on catching up to the master and learning his secrets. While Iwata is now technically Miyamoto's superior within the company, he is still (by his own admission) "the biggest Miyamoto fan in the world," respecting him as the man who "set down the basic grammar for video games."

Iwata (right) and Miyamoto fielding questions at the Japan Foreign Correspondents Club in December 2006. As a fellow creator of games, Iwata was always in pursuit of Miyamoto. [Photo © AFP/Jiji]

Yet as Iwata says, "It's as though the man who wrote the rules went and broke them." Indeed, as Miyamoto continues to work on such un-game-like games such as Wii Fit, his reputation as an innovator only grows.

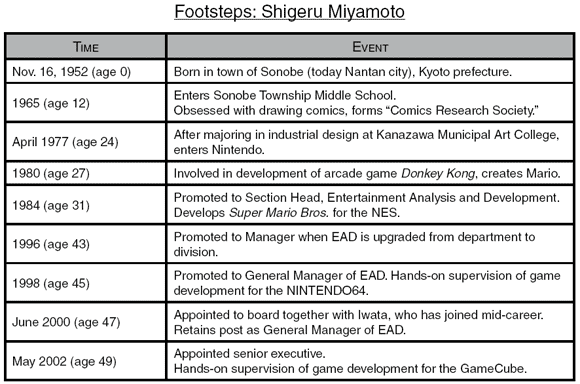

Worldwide, his name is introduced with words like "legendary" and "genius," yet his roots lie in a suburb of Kyoto, among the same backyard hills you can find anywhere in Japan.

As Miyamoto, a native of the town of Sonobe (now part of Nantan City) wrote in the opening sentences for a 2001 column entitled "To All of You Who Hail From Tanba" that ran in the Kyoto Shinbun:

The setting for games like Super Mario Brothers and Pikmin comes directly from mountains like Komugiyama and Tenjinyama. I scrambled around the shrines at their peaks and down their slopes, detective badge pinned to my shirt as I searched for cave...

He spent his early years covered in mud from scampering about the mountains, fishing, and poking around in caves. It was there that he formed the memories that would come to inform his games.

A small town of ten thousand-odd people just shy of an hour outside of Kyoto on the San'in rail line; it was there that Miyamoto was raised, attending the town's public schools.

While he was by turns mischievous and innocent as he ran about the town, his drawings also received praise from his first grade teacher, and he grew to love drawing. By the time he entered middle school he was deeply enamored with comics and founded a "Comics Research Society" with his friends. In high school, he joined the mountaineering club and hiked Komugiyama with a backpack full of sand for training.

Miyamoto enrolled in Kanazawa Municipal Art College to pursue a career in industrial design, which he felt would mesh well with his fondness for plastic models, crafting, and toys as well as drawing and sculpting.

It was around this time that he learned music. He practiced guitar on his own, forming a band with some friends. Experiencing the joy of creating music with other people -- no matter how clumsy -- ultimately found expression in Wii Music, a game that let even the rankest amateur join a jam session with a wave of the Wii Remote.

Thanks to his free-spirited upbringing, when Miyamoto approached graduation he decided it would be a lot of fun to work at this toy company based in Kyoto and went for an interview.

At the time, Nintendo was moving beyond card games. To break into the video game market, Nintendo needed people with expertise in art and industrial design.

So it was that Miyamoto came to work for Nintendo in 1977, at the age of 24. He was the first designer the company ever hired, though his work began with nothing but poster and package design. Four years later came a turning point -- and the beginning of a legend.

It wasn't as though Miyamoto had originally come to work for Nintendo to do videogames; he was not a programmer like Iwata. What first distinguished him as a game creator was a 1981 arcade game meant for export to the US.

At the time, video game arcades were sweeping Japan, spurred on by the success of Taito's Space Invaders game. Nintendo wanted a share of this business and was well into the development of their own arcade game. Their Game & Watch series of portable electronic games, introduced in 1980, was meeting with success, and Nintendo devoted its business resources to developing two arcade machines.

Nintendo of America (NOA) was incorporated in 1980 to facilitate expansion abroad. However, a major part of this push, a game called Radar Scope, went largely unsold.

In response to the request from NOA to develop a new game that could run on the existing Radar Scope cabinet and hardware, the home office decided to create a game based on one of their Game & Watch titles.

With Game & Watch's ongoing success, there was no way they could form a new development team just to make up for an overstock situation in America. In searching for their salvation, what came up was a game already in development as a new title for the Game & Watch series: Popeye.

Popeye -- based on the American cartoon -- would have name recognition. If they could load it onto the excess Radar Scope cabinets, they would have no trouble selling them, the logic went. It was onto this project that Miyamoto's boss invited him.

However, licensing problems froze the project in its tracks -- Nintendo was not allowed to use the likeness of Popeye or any of the related characters in the game, even though development of the gameplay and levels was proceeding well. They would have to create alternate characters. Miyamoto-the-artist's day had finally come.

Instead of Popeye, Miyamoto created "Mario." In Olive Oyl's place was "Pauline," and instead of Bluto, there would be "Donkey Kong." He proposed new ideas like "Donkey Kong throws barrels" and "Mario jumps to evade them," which were added. It was his debut as a game creator.

Miyamoto designed the Mario character with an outfit that would fit with the game's setting, which was a construction site, and added a mustache, which would be discernible even with the coarse graphics. Originally he just called the character "the ol' man," but when the game was shown to a Nintendo of America employee, he claimed the character looked just like a colleague named "Mario." The rest is history.

Unlike its predecessor, Donkey Kong did not go unsold. Far from it -- orders poured in. It was a huge hit, ultimately selling over 60,000 units. Miyamoto had discovered the joy of game design. It was the beginning of a flood of popular games from the designer, and his ascent to worldwide recognition.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like