Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Here's a short story about the making of Nihilumbra, its release on iOS and, one year later, its arrival to PC. Some insights and reflections about designing a game and getting it reviewed that may come in handy to studios trying to create an indie title

Nihilumbra, as you may know, is an indie puzzle platformer where you play as Born, an entity created from the Void, a huge mass of nothingness. In the game you set yourself free from the Void’s grasp and you start travelling the world trying to gather knowledge and experience to be someone in the end.

What you may not know is that this is exactly the same story that we lived as BeautiFun games, our small studio.

In our case, we were also born out of nowhere and we appeared in the videogame world with one clear objective: launch our first game without dying trying.

This is exactly what I want to share with the readers: the story of what we did, how it worked, where we succeeded, where we failed and what did we learn through the process.

Our first step was to design a game accordingly to our needs, our strategy and our philosophy as the purist nerd gamer kind of developers we are. Something that would allow us to earn enough to make a second game without falling into some monetization practices we were just against.

To do so, we decided to release our first game on iOS, since we considered that it was safer: on iOS you can publish everything you want (as long as it doesn’t have sexual content), while on consoles you need someone else’s approval before being able to publish your game. On iOS we were sure that we would reach some audience in the end.

Starting from that point, I had to design a game capable of using this platform’s advantages while avoiding the limitations. Also, we wanted to port the game to PC in case people liked it, so I kept that in mind while making the initial design. That’s how the painting mechanics came to my mind. It was something that would fit perfectly on a touching interface and, at the same time, would be easy to port to keyboard+mouse controls.

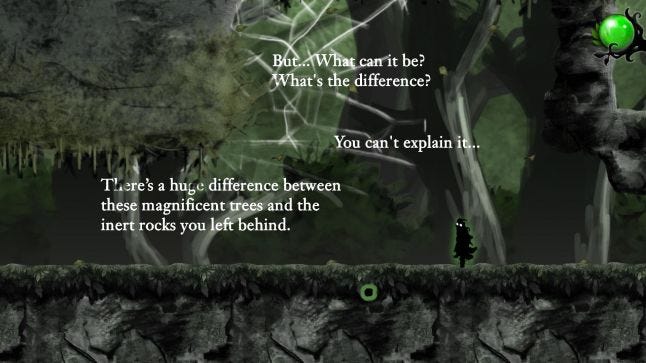

Also, the story was something really important for us, so I worked on a simple but deep story based on philosophy. Why did we decide to make a philosophical game? That's simple, I thought that it would match with a puzzle mechanic; the main point of both philosophy and puzzle games are questions, not answers. However, we thought that while some people would enjoy this kind of story, others would think of it as a useless fill for a puzzle game, so I decided to keep all the storytelling of Nihilumbra in the background. Curious readers would be able to follow the story, and the ones that just wanted straightforward puzzle solving won’t ever be disturbed or stopped because of the story. But… who would be the narrator? iOS players usually play their games during short gameplay sessions, about 5-15 minutes. I need the texts to be repetitive, clear and stubborn enough so players could understand the story even if they played 5 minutes every two weeks, so I decided to make the narrator as the main character’s inner monologue (though that’s never said in the game). When the danger is bigger or the character is scared, there are more texts and they are more pessimistic, and when things go smooth, the texts are more confident and there are less of them.

Alright, but what about gameplay? The audience on iOS is, usually, less experienced than in other platforms. We are not famous, we have no previous titles in the market, no friends on press or the industry and basically no one knew who we were, so the only thing we could rely upon to get visibility was the game itself, and we couldn’t afford to lose players because of the game being not accessible enough. The premise was: if someone wants to try our game, they must be able to enjoy it even if they don't have previous experience with videogames.

That’s why I designed the levels of Nihilumbra with a really smooth difficulty curve, an organic way of introducing new abilities and combining them; everything while keeping things really simple and clear. The tutorials of the game, for example, were created according to this. The players are teleported to a safe world where they can experiment with their new abilities before going back to the real world to face real dangers again.

Some puzzle-platformers classics from where Nihilumbra took its strongest influences.

But that was not enough. To be sure that the game was accessible for everyone we used a static screens system, instead of a scrolling camera, just like Abe’s Oddysee, Heart of Darkness or the first Prince of Persia did. That way, players would always see the puzzles one by one, focusing their efforts on solving them before moving to the next screen, and forgetting about the previous screens really fast.

But there was still a problem. We are all crazy gamers (I beated Sonic the hedgehog when I was three; my parents didn't know if I was a genius or a freak (they still don't know)) so we didn't want our game to be that easy. But... we couldn't make a longer campaign because we were running out of cash and we needed to release and, on the other hand, we didn't want unexperienced players to be unable to complete the main story. That's why I came up with the idea of the Void Mode. (SPOILER ALERT!)

The game itself tells you at the end:

You are free, at last. (credits)

The Void will never chase you again. But you are not free. The world has been destroyed and that will prevail in your conscience, unless you fix it. Your duty now is to remove the Void from the world. Then you will be really free.

What this means is that you are technically free, but you are carrying a burden. This means that you have completed the game and you can walk away and play something else, but you'll leave Nihilumbra's world destroyed. If you want to clean your conscience is up to you. From now on, it's your choice to try to finish the game or not. In other words: I, as a game designer, will try to make the game as hard as possible and you, as a player, have to outsmart me to beat the Void levels because I won't help you like I did during the story mode.

This mode fixed everything. Now, unexperienced players were able to see the whole story and quit after that with a smile; on the other hand, the most experienced ones found a huge challenge in the Void Mode, where the real puzzle game starts. Turning the whole campaign into a tutorial for a bigger, harder game was something that couldn’t go wrong. (Actually we were surprised when we started receiving emails from people that beated the Void Mode without being expert gamers) We even had a really original reward at the end of the Void Mode: a new language!

But… how did things went after releasing the game on iOS?

Everything worked just fine.

We released the game on iOS with a really crappy marketing campaign (we indies simply can’t do proper marketing), but great stuff started to happen. We won a prize on a local TV and radio show, we were game of the year on some sites, we had an 86 on metascore, an average user rating of five stars, we appeared on a list of Apple’s best games of 2012, we won an indie prize on a Casual Connect, a Best Game design award on Barcelona’s Gamelab…

Everything was great. It seemed that our little design tricks worked perfectly. Non gamers found the game interesting and accessible and the experts were enjoying the Void Mode. We even received an email of some man who bought the game for his grandson and ended up playing it himself (He said it was his first videogame ever!), and I helped a woman from the other side of the world to beat the Void Mode through emails, because she said that she really wanted to (and she did it in the end).

We were absolutely happy and optimistic and we decided to create a bigger, better and awesomener version of Nihilumbra to be released on PC. Our goal was to create the game that it would have been if it were developed for PC from the very beginning. The standards on PC were higher, so we had to improve a lot of stuff to earn a place there.

We invested one year on the PC version: we remastered the whole soundtrack to make it sound better, we added weather effects, an art gallery, we replaced all the textures for HD ones, we added new languages, achievements, we redesigned all the menus, adapted the controls, improved the particle effects… The hardest thing was to adapt the game to wide screens and avoid using black frames on the sides. Since Nihilumbra had static screens, the whole level design was compromised when they became wider; we had to modify all the levels to be sure that no puzzle would be spoiled.

We also added a narrator with a really deep and awesome voice that reads all the game’s texts. It is something that really adds to the general atmosphere, but considering that it wasn’t on the original game, we decided to give players the option to mute it.

After one year (and a really tough time on Steam’s Greenlight), the PC version was ready. We thought that people would love it since it was way better than the original game, but… how did things went after releasing the game on PC?

A lot of things went wrong.

First problem! We have an iOS stigma that makes some people automatically hate our game without needing to try it. It’s absolutely true that there are some lame iOS ports on the PC market which make people don’t trust this kind of games, but it’s a serious problem for us that some people prejudge us without considering the effort and the time we invested to create a great new version.

Second problem! Some people hate the narrator. There’s a lot of players who love it, but others just can��’t stand it. They say that it talks too slow and that it’s bothering and anticlimactic, or that it’s not adding anything extra to the game since its repeating the written texts from the background. We’ve been punished really hard on some reviews for adding this feature, which is really sad considering that it can be muted.

Third problem! The Void Mode sometimes goes unadvertised. Since it comes after the credits, some players quit the game before trying it, or they think of it as an extra difficulty mode instead of a part of the experience. For this reason some reviews say that the game is too easy and short. Maybe part of the error was to call it a “mode” on the first place.

Fourth problem! The difficulty of the Void Mode is too damn high! That’s just true. The Void Mode is as hard as I could do it. As I explained, it was designed to be beaten only by players that wanted to accept the challenge. Just as old games did. Take a look at Ghouls and Goblins: everything there is designed to kill you, not to scare you while you are obliterating enemies with some cool moves on your way to the end. I never finished that game, but I love it.

Fifth problem! The story is pretentious and boring and it bothers people while they try to play. Once again, it’s a problem that shouldn’t be really important, considering that it’s always on the background and you don’t even need to read it if you don’t want to.

For all these reasons, the PC version is not working especially well, and we were failing to understand why the same game was enjoyed by so much people one year ago and right now it seems to have so many flaws. But we’ve discovered something that really makes sense…

We haven’t received a single complain from players on any social network. Actually, we are still receiving compliments, lots of messages thanking us for creating Nihilumbra, and on Twitter everyone seems to enjoy it. Also, we realized that small blogs really liked the game. The only ones that weren’t enjoying it were the big sites and some youtubers.

For some reason, it seemed that people paying for the game were enjoying it a lot more than people receiving press codes.

Why is that so?

From my point of view, the key to solve this mystery relies on the differences between the marketing campaign that we did for the iOS version and the new one.

As I said, when we released the game on iOS we did a really bad job communicating it. Basically, we tried to send some emails manually to important sites, but the people who published a review of the game were just the ones that were really interested on it.

On the other hand, for the PC version we sent a press note explaining the great reception of the game, the prizes that we won and we delivered like a gazillion press codes. Basically we did our best to try to be reviewed by everyone we could. That means that our game was going to be tried and reviewed by people that weren’t previously interested on playing it.

And we weren’t ready for that. I designed Nihilumbra so everyone who is interested on it would be able to play it and enjoy it, no matter the gender, the age or the experience, but the game is not designed to hook you up while you are playing it if you don’t have a disposition to enjoy it. There’s a lot of ways of drawing players attention, like adding explosions, sex, mysteries or fast paced gameplay, but we don’t have any of those. That could explain why some important reviewers fail to connect with the game, since they have a lot of titles to try and not too much time to savor all of them.

Our game is meant to be played slowly, with interest and patience, and I believe that rushing through it could lead to an unsatisfying and empty experience.

All these are just theories, mere debate material, but if you seriously think about it, it makes perfect sense considering the way videogames are becoming. Take a look on the newest triple A titles and you’ll see that they compete on spectacularity, graphics, theme, and a lot of them start to become boring after the first awesome twenty minutes.

Is the press leading the industry on that direction with the necessity to get high scores or is the massification of games decimating the amount of patience and attention players can dedicate to every game? The fact that a whole game analysis can be synthetized into one number proves us that making a game that appeals to the most of the press is a certain key for success.

In our case, we designed the whole game thinking only about the player experience assuming that they wanted to play it, and it seemed to work perfectly while we were on the iOS market, but the game should also be ready to catch someone who doesn’t really want to try it, because that’s the attitude that some reviewers will logically and inevitably have.

We’ve learned that it’s not the same to make a good game than making a game people wants to talk about. You have to do both. And that’s what we’ll do in the future.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like