Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

How to organize and direct your thoughts and feelings from a narrative and cognitive perspective in the design of an engaging and dynamic game system. What to keep an eye on when initiating the design process to avoid constraints and pitfalls.

“Putting into play” originates from the site Narrative Construction, and is part of a project whose goal is to offer a hands-on approach to the design of an engaging and dynamic game system from a narrative and cognitive perspective. The series illuminates how our thinking, learning, and emotions interplay when the designer proceeds from scratch to reach the desired goal of a meaningful and motivating experience.

Continuing from the previous part of Putting into play on building a narrative and cognitive core to approach the design of an engaging and dynamic game system, I will eventually get into greater detail on how you organize and direct your thoughts as you proceed from a starting point before the premise has been formulated and the goal of what the player should experience or feel isn't settled.

The specific phase of the design process I am focusing on is usually preceded by a vision that is commonly held by a company, which contains an invisible hierarchy of thoughts and feelings. When the company grows, so do the strategies and methods to control the beliefs, experiences, expectations, and desires, which also define the cognitive and narrative constraints and possibilities you will face as narrative constructors (designers) during the process (see Part 1, where the umbrella term narrative constructor is explained).

When proceeding from the initial part of the design process, you have a tangible sense of anticipation as you know that every single decision you make will have an impact on the result. To control the process and ensure that everyone’s thoughts and feelings are directed towards the same goal, the conveyance of thoughts into a conceivable part that is understood by all becomes crucial. The side effect, however, of lowering the high abstraction level to become visible to everyone who is involved in the realization of the game, could make it hard to discern the narrative and cognitive constraints and possibilities. By putting your faith into methods, models, and structures, you are also subject to narrative and cognitive pitfalls.

Most of the narrative and cognitive pitfalls occur in the interface of going from a vision in your mind to the hands-on phase of realizing a dream. Whether you are working alone or together with others in the development of engaging game experiences, there are three key points to watch closely and act upon to avoid pitfalls:

- Beliefs that could block our thinking/learning from exploring new experiences.

- Beliefs that could block the desired goal from being reciprocally shared.

- Beliefs that could stress the need for control and maintain old beliefs.

Most of the pitfalls related to how our beliefs, experiences, and expectations work that could have a blocking effect on the possibilities to explore the full potential of an idea can be avoided at the very start of the process. I will attend to some of the most typical narrative and cognitive pitfalls that occur when the subject (s) and condition (s) of the premise aren't yet identified.

While I will gradually move towards the hands-on part of the design process, I will provide the concept of learning and some cognitive and narrative primary keys that can help us discerning constraints and organize and streamline thoughts/feelings to be directed towards the desired goal of engaging and dynamic game experiences.

If you haven’t read the previous parts of the series, here are the links to Gamasutra:

Part 1 Putting into play - A model of causal cognition on game design.

Part 2, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective I

Part 3, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective II

Part 4, Putting into play - How to trigger the narrative vehicle of meaning making

The culture within the design of interactive experiences usually focuses on the receiver's desires and expectations. We easily miss the desires and expectations of peers, as we believe that someone else has made sure that everyone who is targeting the desired goal is on the same page. This often leads to trouble later in the process when the thoughts and feelings are unfolding, and people's expectations and goals turn out to vary.

Since the goal is what unites our thoughts and feelings in the design of engaging and dynamic game experiences, the constraints we face from the cognitive pitfall are the difficulties to discern if the reciprocity of the goal is based on shared beliefs or shared desires. What separates the two mindsets from a cognitive and narrative perspective is that the desires as a goal capture our ability to imagine/think, whereas the beliefs could be what holds back our ability to imagine and explore new experiences. And if you are spending endless hours on meetings debating the goal, the advice is to check if the opinions about the goal are beliefs- or desire-oriented as the opposites often create a wrestling match.

The question is, what can we do that hasn't already been done within the design of interactive experiences to avoid the cognitive pitfall?

What’s intriguing is when we try to correct a constraint from a cognitive pitfall is that we are likely to include the pitfall into the methods we invent to streamline the design process. An example of this is the methods we use to avoid conflicts, and where the rule of brainstorming not to oppose others’ opinions or ideas reveals our awareness about the negative impact that contrasting beliefs and meanings have on our thinking and emotions. Thus the method is applied on a specific occasion to allow our imagination to flourish. Without solving the cause of the conflicts, we then leave the brainstorming session as if our imagination is done with its job. Whether we unconsciously use the method to express an expectation on people's behavior that is to turn off the imagination for the remainder of the process after finishing the brainstorming, I leave for others to figure out.

What is important to remember is that not all constraints are pitfalls. They could just as well be a natural part of the learning process when solving problems caused by limited resources. The constraint could then be what leads to the possibility of exploring new experiences and inventions. The same holds for our beliefs and experiences that could be comprehended as a contrast in the form of a constraint but turn out to be an opening to something new. This is why a focus on the desired outcome helps the designer to avoid pitfalls due to preconceptions and triggers the imagination and the motivating engine of learning.

If we turn to how our mind is processing information, we can get a clear idea of what it means to trigger our imagination and the motivating engine of learning. By allowing our core cognitive activities to perform at maximum capacity if we want, we can turn into bloodhounds in the exploration of new experiences.

The ability to generate inter-domain causal networks, use network understanding to speculate about potential outcomes, test and re-adjust our imaginative hypotheses, and to shift attention from one target to another, while keeping in mind the ultimate goal (e.g., subsistence) over an extended period of time is unique to the human mind of today.

Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017

According to the description of dynamic forces of our cognitive activities, targeting an ultimate goal accommodates speculating, testing, re-adjusting, and attention shifting between targets. This is when activities like comparing, distinguishing, and selecting, among others, take place. If you add the speed at which we are processing information, minding how emotions assist our thoughts by retrieving information from our memory, it isn't hard to understand why the setting of a reciprocally shared goal is crucial to the process of reaching the desired outcome. Neither is it hard to imagine why so many hours are spent on meetings when every single mind, belief, experience, and expectation needs to be tested and re-adjusted. Co-ordination of minds is essential because we have everything to gain from knowing how our causal thinking and understanding work.

When setting out to discern constraints and possibilities in the design of an engaging/dynamic experience, I feel very connected with the character Lucifer in a television series with the same name, which is about the devil that ends up working for the LAPD when on vacation in Los Angeles. What Lucifer does in every episode is also the first thing I do, which is to ask what people desire.

But don’t worry, the similarities end there. Or do they?

Our beliefs and expectations could vary, which would cause constraints to the possibility of uniting the minds to target a reciprocally shared goal. The question is, what do you do with the information of someone else’s desires?

Let’s assume that Lucifer is our peer and that we asked him what kind of game he would like to create. We would most likely hear Lucifer share his beliefs on sex, drugs, and punishment and that everyone held the same desire. I would guess that most of us would perceive an indication of a long meeting ahead. As we easily slip into debates, it isn't so much what Lucifer says that could cause a narrative and cognitive pitfall. Instead, it is our beliefs, preconceptions, and meanings about Lucifer that could become a constraint to the motivating engine of learning. So to loosen up the narrative patterns we hold, which contains our beliefs, experiences, and feelings, the reason you are targeting the desires is to open up for the possibilities to imagine new patterns. But if the beliefs to agree upon each other’s meaning is the way to streamline the process, it is then a cognitive constraint occur which could harm our core cognitive activities to perform at full capacity. The only way to go is to look beyond the beliefs and meanings of people. But how do we do that?

It would seem that we believe in agreeing on other people’s opinions and beliefs is the way to set the process in motion. The first part of Putting into play (link) and the 7-grade model of reasoning where the 3rd grade describes how we read others’ thoughts, beliefs, experiences, intentions, and feelings as being similar to our own. The advantages of the 3rd grade are that we can understand others’ thoughts and feelings, more or less. Furthermore, we can also imagine the shared outcome of an engaging experience.

A consequence of the above is the assumption that sharing a goal is equal to having the same beliefs and sense of meaning, and that the need for control in the process quickly gathers people with the same belief. The cognitive and narrative pitfall here is the unconscious building of a group that maintains and repeats familiar structures of beliefs and conceptions.

A “learning bias” occurs from believing we learn while we are repeating patterns of a belief. The way to recognize this pitfall is if something unexpected happens that unsettles the group. Whether we manage to discern the cognitive constraints depends on how, or if we react, and if we will reject or embrace the unfamiliar.

A great example of "learning bias" of a group with the same mindset of beliefs comes from the game designer Fumito Ueda. In an interview, he describes how his peers, during the development of the game Shadow of the Colossus, were laughing at the sad music played when a foe was taken down. Being used to the rewarding fanfare of defeating a boss, the peers thought the sad music Ueda had added to enhance the emotional experience was a bug in the game. As we need to look beyond beliefs and meanings to discern the cognitive and narrative pitfalls, we might wonder how many "Uedas" that we are missing. But if we genuinely wanted to prevent ourselves from having a "learning bias," it is not Ueda we should look at but his peers and their reactions.

I’m not particularly fond of using the term “bias” when naming cognitive constraints, as it’s commonly used to point at a specific group without reflecting on the likeliness that we are ourselves part of a pattern. We have to consider the dual nature of our awareness and unawareness of how our thoughts and feelings work, and our capacity to notice that something doesn’t make sense. We easily discard the feeling by finding, what we think, a sensible explanation that regulates the emotional balance, the so-called control. Since it is tricky for us to discern patterns of beliefs that could limit the possibility to explore new experiences, we have, ingeniously, invented a role that unveils the interface of patterns of beliefs.

We call those who are pushing the limits to reveal our patterns of thinking stand-up comedians. Compared to their predecessors, the fools (jesters), who amused kings and nobles with their lives on the line, stand-up comedians at the most risk their reputation (maybe with the exception of Sacha Baron Cohen). I think we can all recall a moment from a film when the fool makes a joke, followed by everyone holding their breath, glancing at the king, trying to anticipate his reaction. Without having to refer to bias, it is right there, in that very moment of life or death, that we can discern the interface between two contrasting systems of beliefs – even those of real-life but (hopefully) with less drama.

To understand how certain patterns result in behaviors, thoughts, and feelings of a system, we need to understand the power structures behind the narrative construction of meaning – in reality as well as fiction. The tricky side of discerning the interface of a system that could limit our learning is that every sign isn’t necessarily one of drama or conflict. The essential detail could just as well be the one we didn’t pay attention to.

There is a story from the Second World War about a cognitive pitfall known by the name of "survivor bias," whose algorithm written by Abraham Wald on how not to disconsider what we can't see, is well known to those working with AI. By examining the airplanes of survivors returning from battle, one decided to reinforce the sections of the aircraft that had been damaged. Consequently, the cause of damage to the planes that didn’t make it back was overlooked. When Wald, from the other side of the Atlantic and far from the arena of war, advised the military to reinforce the parts that had no bullet holes in them, the number of survivors immediately increased.

Hearing this story today, we react with amazement at how something as obvious as examining the planes of those pilots who didn’t return could be missed. Although, what the story (i.e., the narrative construction) does is to reduce the possibility of getting the full picture of the circumstances. Drawing on the knowledge of how our core cognitive activities work, the question is: why weren’t people able to realize the obvious eighty years ago?

What we do have as a lead to answer the question are the gut reactions of something that appears peculiar and odd. A simple way of discerning a cognitive and narrative pitfall of bias is if the story told makes us feel better and smarter than others. But, looking beyond the sense of meaning, we are not enlightened about the ways Western culture has historically dismissed the narrative as a cognitive process and how our thinking and feelings work in favor of what can be seen and felt. When we hear the story, we don’t get the full picture of the narrative and cognitive systems and their dynamic forces as all the light is on what can be seen and perceived. Therefore, we overlook the narrative and cognitive aspects of taking perspective and position in space when imagining causal, temporal, and spatial links of objects. Given the privilege, we have today of imagining the circumstances depicted in the story, but where the framework of imagination eighty years ago is omitted, we consequently miss out on a dimension of emotion and fear that explains how the need for control can have caused a “survival bias” where saving resources clashed with saving lives.

Interestingly, we never miss a good story about a unique individual like Ueda (see Part 1, Putting into play), and in this case, Wald, who, from the other side of the Atlantic and with the help of mathematics, managed to see what others couldn’t. Once again, this demonstrates the dual nature of how we use our imagination without acknowledging it. This is due to the pattern of beliefs maintained by Western culture to generally only confirm what can be seen and felt. And that’s why the 7-grades model of reasoning, published in 2017 by Gärdenfors and Lombard, is an opening to explore what we believe we can’t see but where the 4th grade explains how our mindreading works by using intuition. Intuition is the interpretation of traces in the presence that point to activities in the past, which help us make assumptions about the future.

Here I would like to stress the point I was making earlier about how, when we are reading causal, spatial and temporal links, we should pay attention to the gut feeling of things that don't make sense. As it can be exhausting to continually pick up cues from feelings, I would like to provide an additional helper to avoid pitfalls caused by commonly held beliefs, which makes me return to Lucifer to see what we can learn from the devil.

The core of the television series is to depict Lucifer surprised by not having his beliefs and expectations on humanity confirmed. What differentiates Lucifer from us as designers, from a cognitive point of view, is the fact that he is taken care of by a narrative constructor who is looking after the pacing of Lucifer's learning. The narrative constructor achieves this by having the devil questioning his experiences and beliefs when interacting with others.

In reality, however, we need to become our own narrative constructors to ensure that our beliefs and expectations won't have a blocking effect on our learning and where a feeling of surprise – even if we don't agree – could be the opening. This is why I have repeated throughout the series to have curiosity as default.

Curiosity, as default from a narrative and cognitive perspective, may seem like a flimsy framework when trying to communicate beliefs and meanings to organize and streamline thoughts and feelings to be directed towards a reciprocally shared goal. By recapturing how our core cognitive activities work, it may be easier to visualize how the mind-set of being curious could work as a motivating engine of learning.

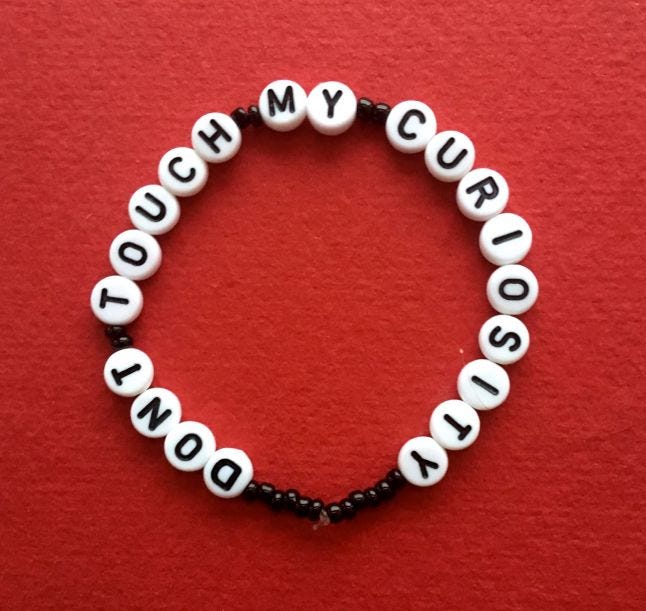

Let’s look at our thinking as a technique similar to a 100-meter sprinter and compare the lifting, forwarding, and shifting legs with the mind’s generating, testing, re-adjusting, and shifting attention from one target to another while holding on to a unique goal. Here, I would like to introduce the motto: "Don't touch my curiosity." In the same way, as the sprinter is guarded against obstacles, we should guard our core cognitive activities' right to perform at maximum capacity. The motto will work as a protection against forces that could have a blocking effect on our ability to learn/explore new experiences as well as a negative effect on our well-being. When finding yourself seeking comfort in Nietzsche's words about what doesn't kill you, makes you stronger, ask instead what made your curiosity wane. You are most likely to have the answer.

You can also use this bracelet as a reminder to always stay curious. The bracelet also functions as your bloodhound in the tracking of other curious minds. When people ask what it says, and you start turning your wrist to expose the letters, you have set the magic in motion. It is not a guarantee but a sign of a possible shared desire to see the motivating engine of learning be put into play.

Under the banner "Don't touch my curiosity" as a means to enter the concept of learning, I will get into greater detail in the next chapter. By adding the narrative keys of perspective, position, and goal to the organization and uniting of the thoughts and feelings, I will initiate the hands-on process and introduce you to the narrative and cognitive forces behind your prime tool as a narrative constructor to control the motivation and the pacing of engagement. I will also establish the basics to how you can:

Discern constraints of beliefs, meanings, and preconceptions during the design process.

Build a bond with the player in the exchange of thoughts and feelings.

Distinguish the different grades of attention and engagement and their effects on motivation.

Continue to Part 6, Putting into play – On organizing engaging and dynamic forces.

If you have any questions, don’t hesitate to ask. It is together that we learn.

Take care, and stay curious!

Katarina

Illustrations by Emese Lukács

Gärdenfors, P., Lombard, M., (2017). Tracking the evolution of causal cognition in humans. In the Journal of Anthropological Sciences 95. p.219-234

Bruner, J. (1991). Thenarrative construction of reality. Crit. Inq. 1, 1–21. doi: 10.1086/448619

Bruner, J. S. (1990). Acts of Meaning. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (2009). Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Return to:

Part 1 Putting into play - A model of causal cognition on game design.

Part 2, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective I

Part 3, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective II

Part 4, Putting into play - How to trigger the narrative vehicle

You May Also Like