Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Nuovo Award-nominated Life Tastes Like Cardboard is a semi-autobiographical game about "boredom and self-pity," delving into the developers own dark thoughts and experiences in their life.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

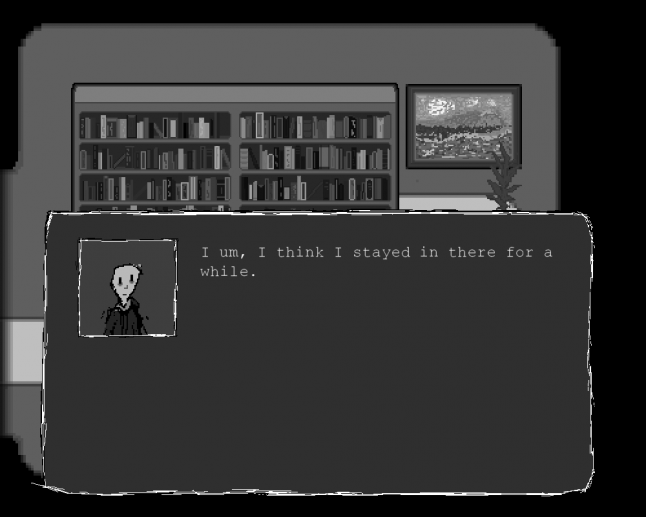

Life Tastes Like Cardboard is a semi-autobiographical game about "boredom and self-pity," delving into the developers own dark thoughts and experiences in their life.

Demensa, developer of the Nuovo Award-nominated game, sat down with Gamasutra to talk about the challenges of learning many things about designing games to tell their story, the emotional toll that comes from creating a sad game, and the worry and relief that came from knowing that players connected with the subject matter.

Hi, I'm Demensa. I made this game. It was my first game. Before this, I never even considered making games because I didn't know how to program and I couldn't draw. Actually, I still can't program or draw. I didn't have experience in writing stories or dialogue either. It shows. Words aren't my strong suit. I had at least written some music before. I think it was important to have one area of the game that I didn't have to struggle, through.

There were an uncountable number of influences for the game, but I'll only mention the two main ones. I remember playing The Beginner's Guide when it came out, and I was blown away by how vulnerable and relatable it was. It explored the ideas of art, relationships, and isolation in a way I had never seen before, and it had a huge emotional impact on me. I ended up scribbling a few ideas for a game that was supposed to capture the same sort of raw emotion and authenticity I felt in The Beginner's Guide.

About six months later, I played Undertale and had a weird emotional breakdown where I decided that I HAD to make a game. I think that's a common story among indie developers. There was a wave of games inspired by Undertale, and I feel embarrassed about how long mine took to make. I wanted to share how I was feeling. How I felt lost and alone. How I felt that nothing was worth anything. How I was scared all of the time.

In the weeks following my playthrough of Undertale, I started coming up with different scenes, lines of dialogue, characters, mementos...There was no solid concept, I just needed to make something.

Gamemaker Studio, FL Studio and GIMP were the main programs I used. Most of the in-game art was drawn with the Gamemaker sprite tool rather than GIMP.

I had to prove to everyone how sad I was!! If I just said, "Hey, I'm sad and anxious. I don't know what to do. I need help," then obviously (in my head) I must be doing it for attention. If I was actually sad, then I needed to prove it by throwing away two and a half years of my life away to make this game.

Working on something sad for so long is difficult. It really takes a toll on you. I felt that I couldn't share it with anyone until it was completed, because it was so personal. There was a paradox where the only times I felt emotionally in sync with the game, were the ones in which I was completely demotivated and couldn't actually work on it. When I could work on it, I couldn't fully empathize with what the game was supposed to be about.

Thankfully, there's enough emotional range in Life Tastes Like Cardboard that I wasn't constantly focused on negative thoughts. I forget sometimes that a large chunk of the game is neutral, or even upbeat.

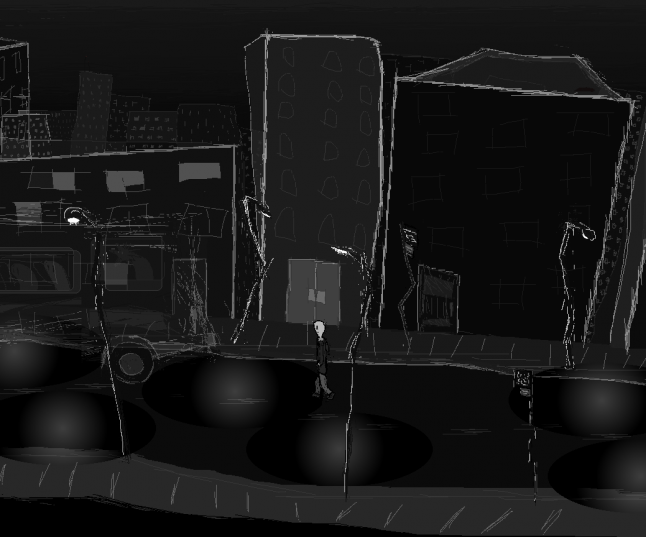

The distinct visual style came about when I stopped working on the game and went back to finish my degree. On the weekends, I would drink enough that I wasn't disappointed by how bad my drawings looked. I would try to draw something, and instead of stopping immediately, I'd keep going until I had something that was at least "finished". This was a horrible strategy to avoid being paralyzed by self-consciousness, but it's what I did.

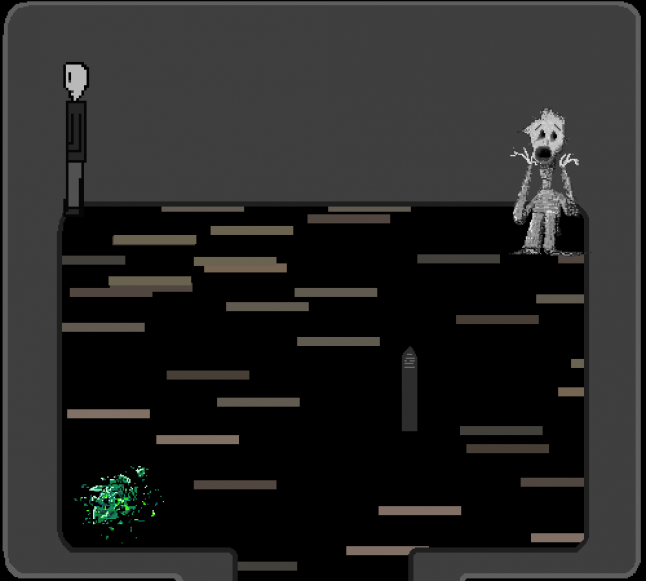

When I came back to work on the game, I had a recognizable style, where I'd use a combination of the 1x1 pixel brush and the fill tool to make things look like they were disintegrating. I listened to music as I drew the art for each area, and I always ended up composing something inspired by what I listened to. Artists like Tim Hecker, Thee Silver Mt. Zion Memorial Orchestra, and Max Richter were staples for the more cathartic sections.

The main thing about the music and audio is that I wanted to compose a lot of it. I didn't want players to be stuck listening to the same song repeat ten or twenty times in a single area. If the music was at least interesting, then I thought the player wouldn't be as bothered by how long it took to move through the game.

I'm a distant person, usually. I don't have many friends and I don't talk to people on a regular basis. I think that as a result, I had (and still have) this incredibly strong urge to overshare things about my personal life. Like, "If I don't say something right now I feel like I'm gonna explode!" I was still self-conscious about it though...

I went back and forth so many times on how much I wanted the main character to be a representation of myself. In the end, I decided on making us pretty much the same person, but with enough minor differences that I felt comfortable releasing the game.

Has making this game helped me? I'm not sure yet. The thing about this game is that it's not at all about facing your problems or attempting to solve them. There's a fantastic interview of Davey Wreden on the podcast Tone Control, where Davey talks about how making a game about a problem you have doesn't actually solve the

problem. Deep down, you have an outrageous expectation that somehow by releasing the game, your life is going to be fixed. I'm still in that indignant phase, where I can't believe that all of my problems didn't go away. I think that making this helped me to know myself better, at the very least.

I'm still surprised to see what a positive response it's gotten. I expected to be laughed at and ridiculed for making such a pathetic, stupid, "cringey" game. That's why it's free, actually. I had so little confidence that I felt like I didn't deserve to be paid for all of the effort I put in.

A lot of people say that they genuinely connected with it. A lot of people say that they feel understood by the game. Like the game is reading their own thoughts back to them. Certainly, it's worrying to hear that so many people feel the same way, but at the same time, there's a huge relief in knowing that you connected with someone. Like, you both get it. I'm so, so, so thankful to everyone who played the game, everyone who left a comment or review, or donated money, or sent me a message telling me about their experience with the

game. It means so much to me, I can't even begin to explain.

The knowledge that you are not alone can be a powerful thing. Is it enough? I don't know.

I feel guilty for not handling the themes of mental illness in a way that is constructive for the player. If you look at a game like Adventures with Anxiety by Nicky Case, you see the same sorts of mental health issues being explored, but it ends with a message of hope and self-improvement. The same thing is true of Undertale. In my game... not so much. In the end I had to make what felt most real to me. Hopefully that doesn't make me a bad

person.

You May Also Like