Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra sat down with Telltale Games' Dave Grossman at Comic-Con International to discuss the upcoming Sam & Max: Season One, digital distribution, and why The Secret of Monkey Island is still really, really funny.

Dave Grossman is the Senior Designer at San Rafael, California-based Telltale Games, currently serving as Lead Designer on the upcoming Sam & Max: Season One, the license for which was recently acquired by Telltale after the IP's previous video game treatment, Sam & Max: Freelance Police, was cancelled by its publisher, LucasArts.

Prior to Telltale, Grossman provided design and programming work on a number of high profile games, including classic adventures The Secret of Monkey Island, LeChuck's Revenge: Monkey Island 2 and Day of the Tentacle at LucasArts, the Pajama Sam and Freddi Fish series for former Lucas co-worker Ron Gilbert-founded Humongous, and most recently provided contract work on a variety of games, including Voodoo Vince for Microsoft Game Studios and a number of serious games projects.

Gamasutra sat down with Grossman at the 2006 Comic-Con International in San Diego to discuss his role at Telltale, the joys of a yellow sky, and what's in store for our favorite dog and rabbit-thing freelance police duo.

Gamasutra: What exactly is your role on Telltale's treatment of Sam & Max?

Dave Grossman: I am Senior Designer at Telltale and Lead Designer on Sam & Max Season One.

GS: At least a couple people at Telltale were working on the cancelled Sam & Max: Freelance Police project at LucasArts, right?

DG: That is true. I'm not sure exactly which ones, but my co-designer Brendan Furgeson was actually one of the writer/programmers on that. I believe some of the artists were also working on that, and I think Randy Tudor [Engineer] was working on it. Some of the other guys became the heads of our company. I was obviously not one of the people working on it.

GS: Do you know how the license was acquired by Telltale? Did it have to be acquired from LucasArts, or...?

GS: Do you know how the license was acquired by Telltale? Did it have to be acquired from LucasArts, or...?

DG: No, no, it had to run out. What happened was they had kind of a lien on it for a couple of years, like an option where if they didn't put anything out for a certain amount of time the license would revert back to Steve [Purcell, creator of Sam & Max], and then once they did...he was happy with the first treatment, and he knew the people, and so they hammered out some new details for a new deal, and off we went.

GS: So it wasn't a situation where LucasArts could have sat on it if they wanted to.

DG: They would have had to release a new game, I think. And clearly they were not interested in doing that.

GS: They seemed afraid to.

DG: Yeah. I think they may be at this point, I don't know, jealous? [laughs].

GS: Do you know how much of that original treatment carried over, if at all?

DG: Oh, essentially none of it. I mean, we couldn't really do the same stuff, we couldn't use any of the assets, and using the design stuff would have been questionable too. Also I, as the lead designer, I was not familiar with that. I wasn't there working on that. So we basically just started over. And we also wanted the treatment to be different. This, coming from Steve himself, he wanted it to be a little more gritty, like the comics. The Lucasarts treatments were always a little more polished up, and we wanted to get a little bit more of that dirt on the streets, and the paper cups and people being mean and nasty. There's a lot of that in the comics, and it doesn't come off in the Lucasarts games.

GS: Are we talking gritty visually, as well?

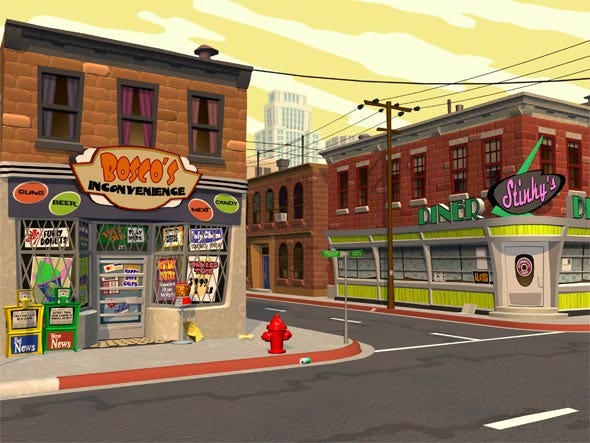

DG: Yes, actually. We sent Steve a screenshot of the street that we had built, and one of his really interesting comments was, "The sky's blue. It probably shouldn't be blue, let's try a yellow one." And boy, that yellow sky just makes it look really filthy and disgusting, and he loved it.

GS: From a business perspective - I mean, obviously you guys like Sam & Max and enjoy working on the property - but from a business perspective, why Sam & Max? Do young gamers, does your potential audience know who Sam & Max are? Does that matter?

DG: Well, yeah. This is obviously a better question for Dan [Connors, Telltale CEO], I was not in on the decision. I'm totally happy about it, sure. Sam & Max has a very strong, devoted, and peculiar fanbase, both the comics and the game have that, and that's actually pretty good for us. We work small enough that we don't need to have the license that's the biggest movie of the year because we're spending $20 million on the game and so everybody in the world has to buy it in order to do it. If we just have kind of a small devoted fanbase, we can make something that's kind of personal and fun.

GS: So that small, devoted fanbase, that's your target audience?

DG: Well, ultimately, we want everyone in the world to play our games, but yeah. I'd say we're not really specifically aiming at a small audience or anything, we just kind of tend to like licenses that are maybe a little bit peculiar, that maybe wouldn't work for other companies. We like to do stuff that has a lot of story and character in it. We're not really trying to make shoot-em-up games, action games. Something like Sam & Max, it's hard to see what other kind of games you can do with it. You can do driving and shooting, but it would be kind of wrong.

GS: You could do a Chase HQ remake...

DG: You need lots of talking, there needs to be a lot of casual time going in the game.

GS: Telltale's digital distribution model, and even first title [Telltale Texas Hold 'Em], seems to be a very casual games approach. Is there a central belief that adventures can work on a sort of casual download basis?

DG: You may be a little off the mark in having us aimed at adventure games. We're not really trying to do that, exactly, we just have a lot of experience making adventure games, and are bringing the things that we learned about storytelling in games from that to bear on the kinds of things we're doing. So we're actually willing to bend away from that and do other kinds of gameplay, as long as we keep the story stuff in focus.

I'm actually pretty interested in where we come down in relation to the casual games space, because basically what we're doing is kind of non-casual casual games, and so the average casual game you sort of pick it up and you play for twenty minutes and you're done, on your lunch hour or whatever, and then you play it again and again and again, whereas ours are more sort of play it for a little while, and you're like oh, wow, I want to keep playing this for a while but, ah, my lunch hour is over. And I sort of wonder how much crossover there's going to be between people who - it seems like casual games are aimed at people who don't have enough time for huge games, and so what we're making is sort of games on a smaller scale, more regular distribution. We kind of have that sort of life set-up. No one else is really doing that, so.

GS: So it would be unfair to call you guys an adventure game developer, it's just the way you see these particular properties, Bone and Sam & Max.

DG: Yeah. I mean, I...did you happen to catch our panel this morning?

GS: No, and I'll tell you exactly why. They decided to schedule the two best games-related panels at the exact same time, and I was at the other one.

DG: Oh, I know, I wanted to see the other one! But yeah, one of the things I was talking about there was just sort of starting from story and/or characters, depending on whether you're adapting a story, you start with the story, and if you're doing something like Sam & Max you just start with the characters themselves and say, 'What's appropriate for these characters? What do they do? What do they think about? What's going to be fun about their lives?' And I'm not particularly attached to any style of gameplay, but we have an engine that's working well for kind of point and click type of stuff. But we're building in a driving mechanic for Sam & Max, and it's entirely appropriate. I'm doing a detective story, I want to have some driving in there. I want to have shooting, and chase scenes, and stuff like that, but that's not going to be the focus of the game. So, again, it's whatever's appropriate to the license, the characters, and the story that we're trying to capture.

GS: So at its core, Sam & Max will be a pure adventure game.

DG: Sam & Max, yeah, basically it's a lot like you've seen already with Bone (above). It's point and clicking and puzzle solving, and we've kind of streamlined the interface a little bit. Things change a little bit for the driving and shooting, but it's still kind of point and clicky. It was interesting to try to make that, actually, because we don't want to change your basic interaction with the game too much when you get in the car and start driving. So you're aiming at the street to go around instead of operating the steering wheel with the arrow keys and stuff like that.

GS: It's fair to say you guys are interested in storytelling mechanics in your games, and research shows that's sort of a major draw for the female demographic. Do you track the genders of your purchasers?

DG: I have no idea, actually! If we do, nobody tells me about it. I don't quite know what it is. I think in general adventure games do a little bit better with the female market, and so do casual games. I think females are the majority of the casual base. And we, by percentage, have more females in the company than most do. It's like, 20, 25 percent.

GS: Well, speaking of your team, can you guys afford to be in California with your sort of small-scale business model?

DG: [laughs] Wow! Um, apparently so, because we're still here. Yeah, I mean, I don't see how any start-up at all can afford to be in California. But actually, things like commercial rents are not that horrible right now, since there's kind of a depression in that market, and our offices are in this weird little hall in a building that's scheduled to be demolished. I don't know if you've been following our website, actually. There was a line on the floor beyond which we weren't supposed to go at one point, since we were only renting half the floor. And then they put up a wall, because they rented the rest of the space to somebody. Just suddenly one day there was a wall. And then we started expanding, and we started looking for other space, and then they made a deal to take up the rest of the space. And so the other day the wall came down, and we're expanding across the tape into a new space.

GS: Beyond the tape!

DG: Beyond the tape now! We're growing like crazy!

GS: Let's talk about humor in games. Obviously you have experience in this.

DG: Yes. I've written a few games that are purported to be funny by certain disturbed sections of the population.

GS: Yes, I have laughed at games you've worked on, and may or may not be disturbed. Is humor hard to do in games? Is it like acting? Is comedy hard in game design?

DG: I think not, actually. But I think that's very personal, because it seems like there are two kinds of people. There are the kinds of people for whom comedy is hard, and there are the kinds for whom drama is hard. I think drama is actually much harder to pull off effectively. If you're being funny, people are willing to forgive a whole lot of other stuff. Particularly, I'm designing a game by putting a puzzle that has a vaguely implausible element to it, and the best thing to do is to just call attention to it and admit it right in the game. Play it up! Can't do that in drama, it doesn't work, it really doesn't work and there isn't anything you can do about it. And I guess it's just the way that I think.

GS: So what are some examples of pointing out this absurdity? I mean, I remember quite a few instances of this in Monkey Island, were some of those your jokes?

DG: Oh, yeah, yeah.

GS: Like, the T-shirt, being just sort of a useless inventory item that you find when digging for gold.

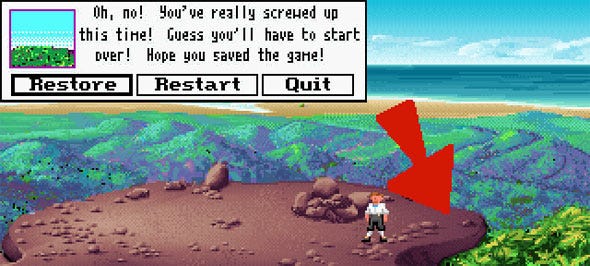

DG: I have a lot of trouble remembering whose jokes some of these are. I do know that we actually, and it was an interesting situation working on Monkey Island because you really had a lot of opportunity to expand on things as we were building it. So, basically because so little had to be decided in advance, the art didn't really take a whole lot of time. There were only sixteen colors, you didn't have to worry too much about "oh, I'm going to have to change this animation, it's never going to work," because the animations were so simple, they were just kind of characters walking around like little puppet theater things. So things like, there's a bit where Guybrush is walking around on top of a giant pinnacle of rock, and there's sort of a dangerous looking bit over the edge. Well, it had just been drawn into the art that way, we didn't really intend for it to be dangerous, but it was easy enough for me to make the little piece of rock crumble down, and jump him off, and copy the little Sierra screen as a little dig at Sierra, and then he bounces back…

GS: "I bounced off a banana tree."

DG: "Rubber tree." [laughs] Oh. And there's that whole scene that happens behind a wall? You're in the Governor's mansion and you have to get the idol? We went back and forth for a week or two, we just kept trying to design that part of the game. It was like, there had to be some puzzles in the mansion, and you have stuff going on with the guard, and some ants and a trail of honey, and it just wasn't working. And finally, I was just joking, I just said, "Well, let's make the whole thing happen behind a wall." And Ron [Gilbert, lead designer] was like, "Hmm! Let's try that!" And I'm like no, I'm just kidding! Really! And he's like no no no, just mock it up, it'll work, you'll see. And…it was good!

GS: How important is storytelling in games? Recently David Jaffe from Sony, the God of War designer, was blogging about how he's come to the conclusion that it's just not all that important, that the real sort of meat of games is the play mechanic, the gameplay itself.

DG: I think you're talking about two separate things, almost. I mean, some kinds of games are just fine on their own. But I think that telling a story with your game makes it more interesting. If you put Doom out, you kind of do that once or twice, and people have done it way more times than that, and it's kind of like oh, I'm playing Doom again, only the characters look different than they did before. And I think something like that is a really good platform for doing something that has a lot more story, elements about a little more complex character interaction, about being able to actually stop and talk to people while people are talking to you. But you can still do a lot of the same sort of mechanics. And I think cross-pollinating those two types of games can create something that's better than either of them.

GS: What do you think of cutscenes?

DG: I like them in very small doses. I kind of learned my lesson on that, Day of the Tentacle had one of the most notoriously long beginnings in any game I can think of. And in fact, we cut it in half. There's kind of an interactive part in the middle where you kind of get to the mansion and it's like, 'oh, let's find the tentacles' and stuff. Well, that was just put in there to actually break up the original cutscene that was something like seven minutes long!

My actual favorite beginning of any game was the one from the original Secret of Monkey Island where Guybrush walks out from out of nowhere up to some guy and just says, 'Hi! I'm Guybrush Threepwood and I want to be a pirate!' And you're off and running, and that's all you need to know to play that game. I'm very much a fan of just giving people the minimum they need to start. You can fill in the rest later. It's good storytelling technique, I think there's a penchant on the part of inexperienced writers to try to say everything upfront.

GS: So cutscenes, not necessarily at the beginning of the game, but in the middle, setting up exposition and stuff like that…is it a shortcut? Or is it a necessity to telling your story?

DG: My life would be a lot harder if there weren't any cutscenes, like if I couldn't ensure that I couldn't get at least two lines of dialogue off without the player running away. If I didn't have them, it would be something where…I could get used that, it would just be a different kind of storytelling experience. You could still do some interesting things. I think of The Sims, which I think is an interesting vehicle for storytelling. It's vague as it is, and kind of playboxy, but you can get more direct with that, with the same kinds of mechanics, and have a more movie-like experience with it without doing cutscenes.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like