Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

After its release, Heavy Rain director David Cage talks to Gamasutra about the perhaps unexpected success of the title -- one that he hopes will make players think, feel, and expect different things from games.

The PlayStation 3-exclusive cinematic action title Heavy Rain came out last month to strong sales and high levels of critical acclaim. While the game has its share of vocal detractors (many of whom have valid criticisms) there's no doubt that the game is bold, takes risks, and is connecting with an audience.

To that end, Gamasutra spoke to the game's director, David Cage, head of French development studio Quantic Dream. Quantic Dream made a critical splash a few years ago with Indigo Prophecy -- known also in Europe as Fahrenheit. Though critics and fans generally agree that the game stumbles by the end, it showed the potential of interactive, cinematic narrative in games. Many say that promise has come closer to being fulfilled by Heavy Rain.

From the nature of interactivity to the game's less-than-perfect English voice acting, this interview touches on different facets of this interactive drama -- and includes a few spoilers, too, so be warned.

Something that I've been thinking about while I've been playing this game is that very often when you're playing a game that's got a psychological component, it concentrates on that. Say it has shooting mechanics; they're not as polished as a shooter, and so the game gets evaluated against shooters and is found lacking.

I felt that your decision to back away from traditional gameplay mechanics actually helped ensure you don't get compared to other games by the players. Was that intentional?

David Cage: It was... not intentional, but we became conscious that that would be the result in the end. In fact, the initial idea was to say: there are some fantastic games out there based on the rules that we've followed for twenty years. These games are incredibly well-implemented, they look fantastic, and technology's great. They follow, by the book, every single rule that this industry has defined for twenty years.

And still, when you play them, you've got this strange feeling that they lack something; they don't have this depth, this meaning, that you would look for -- because they are based on mechanics, and basically it's doing the same thing in different levels with different enemies; basically you do always the same thing. Sometimes you just stop playing and say, "Why am I doing this, by the way?" Yeah, it's fun, but, when I turn off my console, that's it. There is nothing left in me when I stop playing.

When I stop watching a movie that I really like, the movie left something in me that changes my vision, or the way I am, or how I think, or how I see the world, or whatever. But when I stop playing this game, nothing's left. We thought that, if it's not possible to use these rules and get better results -- emotional results -- maybe it means that the rules are not reliable. Maybe we should change them; maybe we should break them and invent new rules that would allow us to go further. That was exactly how we thought of Heavy Rain.

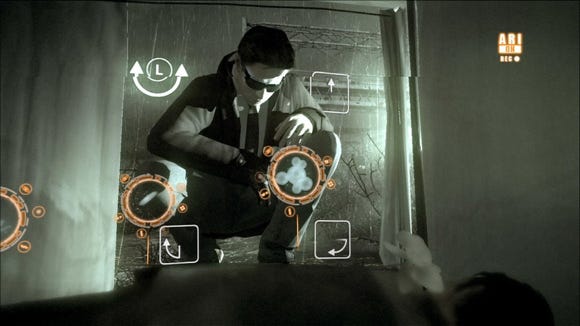

You put the button prompts in the game. With Fahrenheit they were at the bottom of the screen, overlayed. Now they're in the environment. Why do it that way?

DC: In Fahrenheit, you had to look at the 3D world, what you want to interact with: look up and say, "Okay, it's this movement", make the move and look down for the result. Basically, it's really unfocusing. What we wanted to achieve is the fact that you look at something, and you know at the same time you want to interact with this. This is how I'm supposed to do it, and here I can see the result. So your attention is focused only on the object, and you got all of the information at the same time.

That was really a challenge; it was a change we made maybe a year before the end, so it was a massive change. It really changes the entire look and feel of the game. We were really scared that it would look strange with symbols flashing here and there -- that people would just feel, "Oh, this is a video game." It would remind you all the time that this is a video game. And in fact, it didn't happen. We thought it was not that intrusive, and after awhile you don't see them at all.

There is a balance -- there's a certain amount of "gaminess" in the game. Particularly, I'm thinking about things like the power plant: you've got the maze through the tunnel, and the challenge with the wires. How much do you want to stick to gaminess in the design, and how much do you want to back away from it?

DC: I try to back away, but sometimes I feel bad about this and get to feeling I need to do something a little bit more gamey. But I'm happy with the balance in Heavy Rain, because it's almost like a reference to old games, and old adventure games especially. There is also the scene with Manfred when you need to get rid of the fingerprints, which is really --

Which, apparently, I screwed up, but I thought I had gotten it right; but I found out I got into the police station.

DC: You forgot something. Yeah, and that's the kind of gameplay mechanics [we use]. Having a little bit of this is fine when it supports the story -- when it's not just something to keep you busy, when it really means something and has its place in the narrative. That's fine.

Speaking of that part and also the part when the police are asking Ethan what was Shaun wearing, and what time you were at the park, I didn't expect to have to retain information. It seems stupid to say that, because that's the kind of information you would typically retain in real life, but in a game context I'm going to be more worried about what the challenges are. I wasn't expecting to have to remember those things.

DC: It's funny that you mention this because that was really something about role-play. It's not something if you give the wrong answer everything will collapse and game over and this is it. It's just, if you can't even remember the clothes of your son, it really means something about you as a father.

Really, you didn't pay attention, and it was a way to reinforce guilt for the player as the father. This is just role-play, and this is something I used a lot: not every single action in Heavy Rain has huge consequences. Sometimes it's just about the role-play, putting you in the shoes of these characters; making you feel bad or making you feel guilty or whatever. I really like this kind of stuff.

Me too! I was talking to someone last night about this scene towards the beginning where you have custody of Shaun and you have the schedule on the chalkboard, and I did everything.

I got the Good Father trophy. It's a "Ding! You're a good father." And I talked to someone else who's like, "Yeah, I just let him watch TV; he threw a temper tantrum, and I gave up on it." I'm like, "Huh."

At the time, obviously, I felt that, as a player in the role of Ethan, I wanted to be a good father; I wanted to help his relationship with his son. But there was also a part of me that was the gamer that was like, "I want to try to achieve the most that I can with this scenario." So it worked on two levels.

DC: (Laughs) That's one of my favorite scenes, by the way, in the game, because this is an anti-videogame scene in many ways -- because there's nothing really to achieve in this scene. You don't kill anybody; there's no explosions. It's not spectacular. It's just a father taking care of his son, or not, with time elapsing and night coming and stuff. I really love when the house becomes really dark in real-time.

There's something deeply depressing in this scene, and I was really pleased with the results, especially when we showed it for the first time. We were really nervous because we though, "Oh my God. What are people going to think about this scene?" Because, basically, you don't do anything really spectacular.

And the feedback we got about this scene was just amazing because, with some people -- I remember a journalist who was raised by his father because his parents divorced, and he was like Shaun, moving to different houses with crates that were never opened because they were moving out. He felt so depressed about this scene because it truly resonated with his own personal experience. When you can do that, as a game creator, this is the absolute holy grail -- that's what you're looking for.

Chris Hecker has said that in movies the easiest thing to do is shoot a scene of people having a conversation; in games, that's the hardest thing to do.

DC: That's true.

I think that you're aiming at that.

DC: Dialog in games is usually something very difficult and challenging because, when characters talk, the first the thing the player wants to do is skip, and "Okay, give me control again. I want to play; I don't want to listen to people talking."

We tried to find solutions to this by first making these dialogs in real-time, which means that you cannot stay forever without knowing what to say, because the dialog continues without you if you don't choose anything; and also by trying to create, in some scenes, what we call "dynamic dialogs", the fact that you're in control as your characters talk.

That was the case in the scene at the sleazy place where we go with Scott Shelby and meet Lauren for the first time, and you can explore the apartment as you talk to her. I thought it was interesting because it allowed the player to become an actor, and to participate in the performance.

Depending if you want to sit on the bed with her to talk to her, it's going to create this strange feeling of proximity and being close to her and trying to be nice to her. At the same time, if you just look around and take pictures, it really means something different. Again, it's about role-play.

And it's kind of at a subtle level, because you're not really tracking at that granular level, and it's not having an effect on the consequence of the story or anything. It's just about how you feel as the player.

DC: Exactly. But that was the main focus: it's how you feel as the player. I don't believe that every single action has to have tremendous consequences. Sometimes, just changing the psychological state of your character and feeling what he feels -- we did a lot, for example, in one of the first sequences to make sure that you feel responsible for what had happened to Jason when he died. You lost him -- you as the player. You didn't pay attention; you lost him in the crowd and couldn't save him. This strange feeling of guilt is something that we really build.

There's this one part I love in that crappy office in the police station, and there's a part where he's in withdrawal from Tripto and the room stretches. It's a film technique, but since it's a game you can actually make that a concrete thing, whereas in a film it would have to all be through camera tricks; but with this you can actually change the geometry of the room. We're very good at aping film's tricks, but we can come up with our own psychological tricks, our own sort of vocabulary; we construct this world, so we can break it if we want to, too.

DC: Interactivity is a very powerful medium, and we did very little things with it so far: pretty much always the same thing. Often I use the analogy with the movies. The first movies, the graphic quality was very low; there was no sound; they were black and white; the frame-rate was really low. All they could do with it was "the attack of the train" and "the attack of the bank" because it was big and spectacular, and that was fine; but, as the technology evolved, movie makers were able to tell more subtle things.

So they started maybe with a movie like Metropolis, and then there was Orson Welles and more and more subtle emotions in movies, also because the technology evolved and also because movie makers discovered how to use this technology to treat your emotions.

This is pretty much where we are, I think. We are at a stage in the industry where we can stop making the attack on the train or the attack on the bank; we can move to something more subtle now. We should create our own Metropolis and our own Citizen Kane, probably.

Were you surprised by the success of the game? I'm not an analyst, but I have certain gut feelings about games; I thought this game would be popular, but I did not expect it to debut at number one in the UK. It debuted in the top 10 in Japan; it debuted in the top 10 NPDs in a month against things like BioShock 2. Were you anticipating this?

DC: Yeah, the NPDs for February, and we just had one week in February, which is great. No, I didn't expect it to be that popular. I was quite used to having critical acclaim and commercial mid-success. This is honestly what I was expecting for Heavy Rain. I think that no one even at Sony was expecting this. No one even in the most positive reviews we got -- all the critics were saying, "I loved it. I just hope it's going to sell, because if it doesn't it it will be a pity."

But I think the success took everybody by surprise, including Sony, because the game was sold out in the UK in two days; so you couldn't find it on the shelves. You couldn't buy it, pretty much, after two days. So it was really a shock. And same thing in Japan, which is even more of a surprise: the game is sold out. You can't buy it. And that's great; I think it means a lot.

It means something because during the development of Heavy Rain, we said, "This game, whether it's a commercial success or a commercial failure, is going to send a very strong message to the industry about how interested the market is in innovative concepts and games exploring new directions.

If it's a failure, it's going to mean that, for the whole industry, 'Don't change anything! Continue to make the same games because this is what the market wants, and if you try something else you'll fail.' But if the game was a success, it would mean that the market was eager for something deeper and something new."

And I said that last year, before knowing the reviews and before knowing the sales. So now I can say, "Look! The market wants innovation." So this is what we should concentrate on now, and Heavy Rain is a very strong message to publishers to take more risks and support innovation.

And support something with a different texture. I like it for a lot of reasons, but it offers just a totally different texture than other games, both from a gameplay and from a narrative perspective.

DC: Many critics wrote that it was the first game for adults, and, yeah, I take that really as a very strong compliment because most games are for kids and teenagers. Most games are about feeling powerful and killing monsters and doing spectacular things and just feeling strong.

My son is nine years old, and he loves these games, because he's at the stage where he needs to master his environment; he needs to become stronger and take confidence and stuff. These games help him in order to do this. But when you're an adult, this is not necessarily what you want to play because you're beyond this stage. You expect something else. I hope that there will be more games dealing with a major audience. We shouldn't make only games for kids and teenagers.

Sega's Yakuza

The first game I thought was really for adults was -- Sega has a series called Yakuza, and they're gangster dramas. I would put the story on par with Heavy Rain, but the main game part is a punching, kicking fighting game: beating guys up. It's a fun game, and as a gamer I like it, but I think that you have a hard time reconciling those two parts.

DC: The most important thing for me with Heavy Rain was not to put violence at the center. Violence can be used as a narrative device when it supports the story or the characterization, but it's not the end goal; it's not the core of the experience. In Heavy Rain, that's the big difference, because in most games what you do is kill, destroy.

In Heavy Rain, you make choices, and these choices could be to kiss someone or not to kiss someone; it could be to help someone or not to help someone. It could be just to make a decision affecting your psychology or how you feel about your character. I think that was the most important thing.

An analyst wrote that, before the game was released, no matter how good the game would be, it would never sell. He said the reason for that is that gamers don't want to think when they play. I thought that was the most horrible thing to write and to say because that's so totally wrong. People playing games are just people!

And you're thinking all the time when you're playing games!

DC: Yeah, absolutely. Absolutely. It's absurd; thinking and feeling is a pleasure. When you go to a movie theater and watch a film, you really enjoy thinking and feeling and trying to guess what's going on. It resonates with you as a human being, and I see no reason why videogames should be any different.

When I'm playing a game -- like God of War -- yes, it's violent, but I think that violence is abstracted. Even when it's realistic, you know it's not a realistic context. But if you want to up the realism of the narrative -- up the realism of the world -- then suddenly the violence is, in the case of Yakuza, incongruous.

You have the abstract, concrete; abstract, concrete -- a switch back and forth. Walking down a street in Tokyo, even if you're a gangster, you're not going to get into fistfights with -- by the time you beat that game, we're talking like 2,000 guys or something. (Laughs) You know what I mean? It's just not realistic.

DC: Well, that's the problem with most action games: that the story, at some point, needs to justify that the hero goes from jungle level to the snow level to the sand level, so this is already something difficult.

It also has to justify that there are zillions of people attacking you all the time wherever you are; there are people shooting at you because this is what the game is about. So it's really difficult to have decent storytelling in most games, and I think that games like Uncharted 2 or God of War III did a great job at that, trying to have a story really supporting the experience.

At the same time, I made a different decision, which was to get rid of the violence, the mechanics, the patterns in the gameplay. I think that this is not an absolute necessity; there are other ways of offering gameplay than using the same loops in a way.

Did you kill the drug dealer?

Yes.

DC: No hesitation?

Yes, there was hesitation. In fact, after I did that part, I got up at the next break and grabbed my roommate who had already beaten the game, and I said, "Did you kill the drug dealer?" I had to ask him immediately. I had to compare notes. Yeah, there was hesitation; that was a moment where I said, "Look. I know I'm playing a game, so I can..." I knew I had that power because there wasn't a real consequence. So I was able to play around with that.

DC: But is it something you would have done personally, in real life?

It's so hard to say. We're talking about a scenario that's very -- I don't have kids, so I don't have that bond. I can't anticipate what my reaction would be in this scenario at all.

DC: It's difficult to tell what you would do. Did you cut your finger?

Yeah. I've done everything, basically.

DC: Okay. Did you kill the religious guy?

No, I didn't; I saved him. think I do behave differently with the different characters -- with Jayden, I really don't like the other cop. I mean me; I don't like him. I don't like him at all, and I like the rational approach.

DC: That's funny. Many people shot the religious guy when he takes the crucifix out because they thought it was a gun, and it's incredible how many people shot him. It's funny.

Why'd you record the English voices in France? I think that's a common criticism of the game.

DC: Yeah. It's really funny because most of the actors are American, actually. Scott Shelby, Madison Paige, Carter Blake. There are a couple of English actors: Ethan and Jayden are English actors, actually. But there are no French actors.

I haven't heard the English voice acting because I was about a week late in starting it, and everyone I talked to said, "Play it in French with subtitles."

DC: (Scoffs) That's absurd.

Really? You think?

DC: Yeah, it's absurd. I think the English version is really the real version; the original version. But some people probably complained about the accent, and this is something we tried to care about; but actors have so many technical constraints on stage that it was really difficult to fight for everything.

They needed to know their lines by heart. Facial animation... Many technical constraints. A lot of text to record. Plus, you want them to act and to deliver their lines, etc. etc. So, yeah, we'll probably pay more attention to that and probably work with American actors only in the next game to make sure that this is not in the way.

How did you do the recording? Did you just record them in booths, or did you actually have people acting together?

DC: We actually shot in a sound booth for facial animation because it's a different camera setup. They had an actor delivering the lines to them; they were actually acting with someone.

That's just another thing that's different in games; finding the footing, as we move into these more dramatic, serious games that require really convincing acting. To have Kratos shouting like, "Ah, Ares, I'm gonna fucking kill you!" doesn't require the same sort of depth as a guy screaming about his son getting run over by a car.

DC: Mm; agreed. You know, the cast was really amazing; there are some really great actors. We gave them so many technical constraints, and we're working on this. The goal is not to find better actors; the goal is to find ways of allowing them to deliver with less constraints. That's the main goal. But we learn, we discover, we improve the technology and the way it produces kind of things. I also notice that many people felt the emotions that we wanted them to feel, and it's also due to the acting.

Oh, yeah! Even my friends and people I've spoken to -- everyone is feeling the emotions of the game. Well, not everyone; you have to be aware that there are people who totally don't like the game at all, and that's going to happen with any piece of media or art.

DC: Very few, to be honest. Very few, to my big surprise. (Laughs)

Did you feel like you had to set the game in America to appeal to the widest audience? Why not set it in France?

DC: Well, because the genre's really a dark thriller, and it made sense -- as this is a very codified genre -- to use the rules of the genre; and the rule is it takes place usually in the U.S. There are some great thrillers taking place in South Korea, which is also very interesting; so I'm not saying it was impossible to set in France, but that was not how I felt about it.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like