Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Are F2P games morally questionable on a fundamental level? What if we have just learned to cope with the evils of the standard business model of "upfront payment"? A response to Jonathan Blow.

Here are some thoughts I had recently. We are quick to demonize Free to Play, myself included. But what we tend to forget that the "traditional" model of upfront payment has severe issues as well. Those issues have been detrimental to how games have developed and are still detrimental to what games are today.

But before we go into it, here is a recent presentation by Jonathan Blow that summarizes quite well the argument.

Mr. Blow does an interesting analogy here. He compares the issues of F2P games to TV dramas from the 70ies and 80ies like Knight Rider, A-Team or The Six Million Dollar Man. He claims that commercial breaks and syndication rules made those shows shallow and exploitative. He claims it took the Cable TV Network HBO, which got rid of syndication and commercials in favor of a subscription model, in order to elevate TV dramas onto a more serious, artistically ambitious level of today. He cites Game of Thrones, The Wire and (I think) Sopranos as examples of "good" modern TV shows. For him those are good dramas because, unlike the previous TV dramas, the world does not reset at the end of each episode. Rather, the story keeps developing from episode to episode which results in events having staying consequences and characters changing over time. Additionally, they resort less to "cheap tricks" like cliffhangers to retain the audience past a commercial break. Finally, they are generally more serious and less campy in nature.

He argues that the early TV dramas are like F2P games. Because of their business model, F2P games are shallow and exploitative. They HAVE to apply certain tricks in order to be commercially viable. Therefore, their ability to be artistically meaningful is inherently diminished.

To be fair, I made a similar argument where I mocked the very idea of TRAUMA being a Zynga-style Facebook game. To some extend I do agree with Mr. Blow.

But there are at least two major issues with Blow's argument, the first being historical in nature. While HBO has no doubt been an influence, claiming it was HBO that changed TV dramas is a bit of a revisionist history. In fact, a lot of modern TV dramas still do have commercials and are still used for syndication. Even going back to the 90ies it's easy to point out TV dramas that did not exhibit the exploitative features mentioned by Mr. Blow. Shows like The X-Files or Babylon 5 were syndicated and had commercials. But they had also arcs that spanned multiple seasons and often dealt with serious, mature topics. What changed between the 70ies and today is not so much the business model but the mindset of TV producers and the expectation of the audience. A major catalyst for this change was the TV Series Twin Peaks. It combined the format of a police investigation series with the season-spanning arcs of Soap Opera. It was also directed by a film director which introduced a major shift towards film-like aesthetics and themes. Twin Peaks wasn't the only reason. However it contributed to a gradual evolution of the genre: the audience started seeking out similar dramas and TV networks started being more comfortable with a smarter and more mature approach to make their series.

Twin Peaks

Twin Peaks and the discovery of nuance and depth - the maturation of TV drama was not brought about by the change of business strategies.

So a particular business model may modulate but doesn't necessarily completely dictate the potential for artistic value of an individual work. A willing creator ought to be able to use the limitations of it's medium to bring out it's potential. As Nietszche put it so well, art is always about "dancing in chains". The particular issues of the F2P model seem to me to have more to do with the mindset, the goals and aspirations of the people making those games. One could argue that the reason why most F2P games have little artistic ambitions is because it is harder to make those kinds of games artistic. But correlation does not mean causation. It could be just as well the other way around: because there is a lack of successful precedence, making artistic F2P games is hard.

This begs a question - are there perhaps ways in which the "standard" upfront payment model business model for games inhibits artistic expression? We consider this way of monetizing games for granted. What if we have become blind to it's shortcomings. Or what if we have found ways to deal with the shortcomings so they don't even occur to us?

This ties neatly into a different analogy that struck me recently - many modern games (and increasingly other media) bear striking resemblances to US-style superhero comics. On the one had, of course, they actually ARE adaptation of said comics. But in a more fundamental way, the way they market themselves and the way storytelling is structured resembles those comics.

Superhero comics were often designed to create an upfront outrage and sensation - a hype. This is perhaps most evident in the way the design of the covers. Quite often the covers actually had a vital panel of the story on the front showing a major, dramatic scene from the current issue. It hinted at some profound changes - important characters dying, marrying or being in incredible situations. This resulted in a "hook" where an audience might be intrigued in finding out how the details of how the incredible event comes to be and how it eventually resolves. Sensationalist content is being front-loaded to create a high anticipation for what is to come.

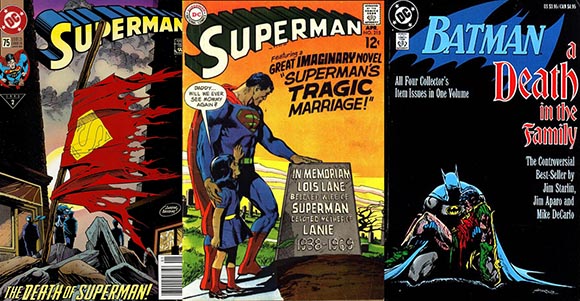

US Comic Book Covers

SHOCKING BRAND NEW ISSUE!!!

This is, of course, a direct result of the business model. The goal is to make the audience pay for the content before they actually consume the content. In order to do so, comics aim at convincing their audience that the content will be well worth their money. They do so by giving the audience samples of the content and they - of course - don't pick just any part of the story but the most shocking part.

But this has repercussions for the actual storytelling. Every single story needs such a hook. It needs to be crass and "in your face" so they can put it on the cover. Characters need to follow well established stereotypes so every dummy gets what this is about just with one image from the cover.

More insidiously, there is no need to actually provide anything beyond that front-loaded content. By the time the audience buys into the content, the creator already got all they needed from them. As long they deliver that one money shot that was promised nobody can complain. So the rest of the story can be just unsubstantial dressing. With a lot of those superhero stories, you get the impression that the writers first came up with a hook and then reverse-engineered some asinine rationalizations for why it happened and some half-hearted, stereotypical resolution. Ideally, the resolution would revert everything to normal so they can do it again in the future. Superman died about twice now. Batman broke a spine and fully recovered. How many Robins did we go through now?

This kind of storytelling is not unique for comics. Films rely more and more on hype generated by trailers. Many scenes in movies are nowadays made specifically so they can be put later in a trailer. Do you know that feeling where you leave a cinema and feel like the trailer gave away the whole movie? This may not be because the trailer went overboard, it may be because the movie was made just to create the trailer and the rest was just filler.

This is also related to the issue of sequels. It's difficult to hook an audience with a new, unknown setting and characters. It's easy to hook them with a follow-up to a story they are already familiar with.

And no medium is as much plagued with sequels as videogames. Almost every major release nowadays has a number greater than 3 in the title. Because it is much more difficult to sample a piece of interactive experience than to sample a panel from a comic book, videogames rely heavily on the establishment of franchises and genres to provide those hooks necessary for the business model. The rhetoric being always - "it's like that thing you know but better". It's zombies but in space. It's soldiers but with dogs. It's that big game from last year but now even larger.

Sequels Q1 2013

Top 10 selling games of Q1 2013. ALL of them are sequels. (source: http://www.vgchartz.com/)

The recent trend of crowdsourcing can be seen as yet another escalation of this model - no longer do we sell games, we sell mere promises of games. We finally got rid of the filler and everything else. We just sell the hooks now. Product may or may not be included in the box.

The results of this market philosophy is profound in any medium. Because what is lost along the way is modestly, subtlety and surprise. All three are difficult and precious in videogames and modern cinema. My best movie experiences were the ones where I had no idea what a movie was about going in. The reason why retro games often feel so fresh is because their modest aesthetics often conceal their richness. Perhaps this is why we are obsessed with avoiding spoilers noways. The only surprises stories provide have become precious and fragile. One sentence can make the added value of actually going to the movie evaporate.

To be fair, I have been harping on comics, movies and games. But it's worth pointing out that both have their fans, who very much appreciate those very qualities I have been criticizing. I can appreciate them myself. This is analogous to, as Blow mentioned, the people who have fun playing Candy Crush or Farmville. The fact that people like something doesn't mean that there is nothing wrong with it and we still may want to look for ways to offer more ambitious alternatives.

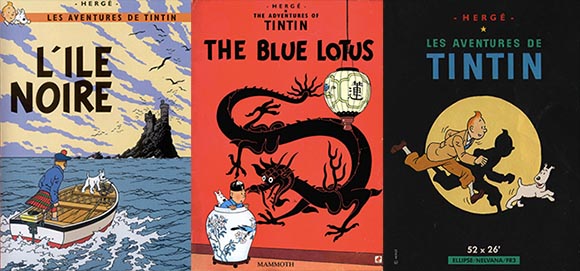

But it's not all doom and gloom. As already mentioned, a business model may modulate but not dictate how we utilize a given medium. Going back to comics, the US Superhero comics were just one subset of a much larger genre of comics. European comics, for example, shared many similarities with their US counterparts, but often chose a less upfront appearance. The stories were longer and not necessarily focused that much on a central hook, allowing for more surprise and wonder. Nowadays we have a wide selection of sophisticated graphic novels next to the old superhero mainstays. Superhero comics have evolved themselves.

Tintin Covers

Tintin covers - evocative but a lot more restrained.

So there is hope that games can mature in the same way TV series and comics did. To some extent we already see it happening. Blow mentioned Going Home as an example. I, for one, am looking forward to his own game the Witness.

Shallow and exploitative games are not just the result of a business model. It takes a certain mindset to create them. It takes a different kind of mindset to consciously resist and overcome the corruptive aspects of a particular business model. There are good reasons to be critical of the hubris and exploitation of F2P games. But it is wrong to categorically dismiss the entire idea as evil at it's core. A similar evil lives in the heart of every kind of economy. Even it it sounds ridiculous at this point, In the future, game designers may find a way to use F2P to pursue more artistic goals.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like