Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Are game design patents helping or hurting developers? Where should we draw the line? In this exclusive Gamasutra editorial, game designer David Sirlin discusses The Trouble With Patents, using Sega's infamous _Crazy Taxi _design patent as an example.

Article 1, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution says that Congress has the power:

To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries;

Back in 1790, the patent examiners who considered each application were the secretary of state, the secretary of war, and the attorney general. Receiving a patent was a notable honor, reserved for important inventions.

In 1793, Thomas Jefferson defined the criteria to patent as

Any new and useful art, machine, manufacture or composition of matter and any new and useful improvement on any art, machine, manufacture or composition of matter.

Today, we say for an idea to be patentable, it must be:

Novel

Non-obvious

Useful

Patents made it possible for great inventors such as Alexander Graham Bell, the Wright Brothers, and Thomas Edison to invest their sweat and genius into expensive new creations. With a patent, an inventor has the government’s guarantee that he can sell his innovation for a limited time without competitors being able to copy the product. After all, why spend money on R&D for new, innovative products if knock-off companies can instantly copy them?

“The patent system added the fuel of interest to the fire of genius.”

—Abraham Lincoln

And then something happened. I don’t know exactly when, but patents — especially software patents — have gone off the rails. It took 46 years to reach the 10,000th American patent, but today, there are more than 10,000 patents granted every three weeks. Perhaps patents could be given out as Cracker Jack prizes—after all, the US Patent and Trademark Office already approves more patents per year than boxes of Cracker Jacks sold at Dodger Stadium each year.

A notable change happened in 1991, when the U.S. patent office was no longer funded by the general tax fund and had to start sustaining itself entirely on fees from “customers.” This framed poster at the patent office’s headquarters gives insight into the office’s mentality:

Our Patent Mission:

To Help Our Customers Get Patents

The more patents, the more fees the patent office collects, and the more innovations we stimulate, right? But what happens when big corporations harvest thousands of patents for the sole reason of locking out competitors? What happens when competitors have to merge with each other to actually make anything? What happens when a cottage industry of patent hoarders waits for the right moment to strike, then demands that anyone who makes 3D games pay a tax? Or anyone who makes a spreadsheet program?

Entrepreneurs are faced with a minefield of seemingly obvious things they cannot implement out of fear of patent lawsuits. Meanwhile, IBM was awarded 2,941 patents in 2005, marking its 13th straight year as the #1 company in volume of patents (it had a much better year in 2004 with 3,248 patents).

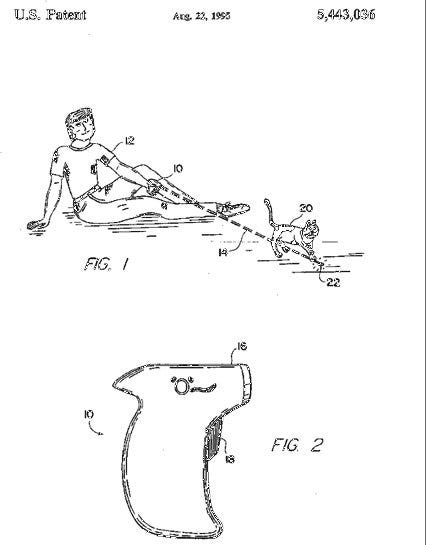

Method of Exercising a Cat

"A method for inducing cats to exercise consists of directing a beam of invisible light produced by a hand-held laser apparatus onto the floor or wall or other opaque surface in the vicinity of the cat, then moving the laser so as to cause the bright pattern of light to move in an irregular way fascinating to cats, and to any other animal with a chase instinct."

What in the world are all of these patents? It’s not exactly the light bulb or steam engine these days. In 1991, Amazon’s CEO Jeff Bezos patented the “1-Click buy” (patent number 5,960,411). That’s the concept where a website already has your stored credit card info, so you can click on a “buy now” button to buy it in one step. This landmark patent was widely criticized, and Jeff Bezos responded by saying that the patent system, as it stands, is broken.

If he didn’t patent this, his competitors would, and they’d use it against him. Bezos is “playing to win” in the game of business, and I can’t fault him for that, but even he pointed out that the rules of the game itself are broken and need to be fixed.

Patents currently give the patent-holder a twenty-year government-sanctioned monopoly. Twenty years might have made sense in 1790, but it certainly doesn’t in the realm of internet (or game) technology. Bezos said that perhaps three years would be a more reasonable number in the internet sector.

One notable patent in the video game industry is #6,200,138 (or ‘138, for short). This is Sega’s:

Game display method, moving direction indicating method, game apparatus and drive simulating apparatus

Here’s a couple lines of that patent, representative of the rest, to illustrate the quality of writing present in this patent:

A game apparatus for executing a game in which a movable object is moved in a virtual space, comprising:

setting means for setting a dangerous area around the movable object;

“Movable object is moved?” If an object is moved, just say so, because it’s clearly movable. “Setting means for setting?” What does that even mean? I’ll spare you the agony of reading through this entire patent, and I’ll just summarize it for you.

Sega made the game Crazy Taxi. Fox Interactive made the game Simpsons Road Rage, a knock-off of Crazy Taxi. Sega sued for infringement based on patent ‘138, which basically says this:

You drive around in a city, rather than a race track.

There's an arrow that hovers around, pointing you to where you should go.

Cars have an invisible aura around them of "danger zone" and a bigger aura around that one called "caution zone." Virtual people in the danger zone jump out of the way. Virtual people in the caution zone stop walking, rather than walk into danger.

The size and shape of the auras described above can change based on the speed of your vehicle.

Now, Simpsons Road Rage and Crazy Taxi are incredibly similar games, and no one is even denying that. But the concept of driving around in a city where virtual people jump out of the way of your car is not exactly what Thomas Jefferson had in mind when he said that patentable inventions were to be new and useful, and you can forget about non-obvious. I also don’t think he’d be too happy that no one can make a game where you drive a car around a city with virtual people who jump out of the way…FOR TWENTY YEARS. The big picture of protecting the R&D of entrepreneurs is certainly not served by patents like ‘138.

Neither is it served by Namco’s patent 5,718,632, giving it a twenty-year government-sanctioned monopoly on using mini-games during another game’s loading screen. I don’t know how else to say this, but the idea of putting a mini-game in a loading screen is “obviously obvious.”

This kind of stuff is an insult to actual inventions. Somewhere along the way, patents started greatly hampering the advancement of technology, rather than cultivating it. One belief is that patents such as Sega’s ‘138 and Namco’s ‘632 are so laughable that they would never stand up in court. Well, they are laughable and I don’t see how they could stand up in court because they blatantly fail the test of “non-obvious to a person of average skill working in the field at the time.”

But the power of the patent is the power to threaten a doomsday not unlike nuclear warfare. Defending against even the craziest patent lawsuit is more than a $1 million endeavor (or at least that’s what patent lawyers tell me). Hardly anyone can afford to take this gamble, and anyone who does has a chance of losing BIG—a lot bigger than just the $1 million ante required to sit down at the legal poker table. When a patent holder sues for infringement, he’s entitled to reap the rewards of the “infringer’s” past sales. This encourages patent hoarders to wait until their prey hits it big, then sue, so the damages are astronomically (and unpayably) high.

And so the mafia-esque bullies will continue to bully. But what about Sega’s lawsuit over Crazy Taxi? Surely a court would interject some sense into this matter. Unfortunately, Fox Interactive was (somewhat understandably) not willing to stand up to Sega’s hollow patent, and so the patent was never tested. This encourages more bullies to bully more companies and demand protection money, while both sides escalate their nuclear arsenal of patents.

I guess I mixed metaphors of mafia and missiles just then, but the current situation is not unlike a war of mafia families with a dash of escalating nuclear weaponry thrown in, so I’ll let the mixed metaphor stand.

A lot of these problems stem from the way the US Patent and Trademark Office goes about determining what is novel and what is non-obvious. To find out whether something is novel, the patent examiner looks at previous patents and at published works to see if there is a discussion of the idea. The problem is that ideas that are bad, trivial, or completely derivative are not usually discussed in published works. In fact, serious publications (the ones the Patent Office would weigh the most) are the very publications that filter out all the bad, trivial, and derivative ideas, so of course they won’t discuss such ideas.

Just because you might not find any articles about “we could make video game controllers vibrate when the player gets hit by something in the game,” doesn’t mean the idea is novel, or that no one thought of it. In fact, so many people thought of it that probably hardly anyone submitted a serious paper theorizing about this feature ahead of time. It’s so far not even a very good feature, and yet it’s patented, and not by Sony (you’ll notice the lack of rumble in the PlayStation 3 controller).

And then there’s “non-obviousness.” The current test of non-obviousness has many problems, a fact that should be obvious by the sheer number of patents granted on obvious ideas. There is simply not enough emphasis on determining whether a person of ordinary skill would find the idea obvious. But there is also a more subtle problem with the process.

Suppose a group of 100 people of ordinary skill in computer programming separately encounter the same problem. This problem is so easy to solve that there are dozens of solutions. These 100 people submit, say, 45 substantially different implementations that solve this easy problem. Then one of them applies for a patent on a specific implementation.

Currently, that one person could claim that his particular solution to the problem was non-obvious and novel. That is vacuously true, as it’s entirely possible that none else used his particular method. In fact, his particular method might be a worse solution than the other 44 solutions mentioned above. Even though the 45 solutions are collectively “obvious,” this one particular solution is considered non-obvious, so the patent is granted.

But here’s the kicker: after he gets that patent, the courts seem to allow him to enforce it against people who used different solutions to the same problem! That’s right, even if your specific implementation to 1-Click buying is different from Amazon’s, they can still enforce their patent against you.

Courts do not always allow companies to get around a patent by using a different implementation to achieve the same goal. In Amazon’s case, Judge Marsha J. Peckman didn’t even need to review Amazon’s particular implementation of 1-Click buying because she considered any implementation to infringe on the patent. So, even if you developed your (different) particular solution to the 1-Click buying in parallel to Amazon and with no knowledge that Amazon was even working on it, you’re still out of luck.

There’s no hope of reform coming from companies adopting different behavior. Companies are merely playing the game with the broken rules presented to them. Reform must come from lawmakers who restructure the rules of the patent office.

More is not better. In fact, fewer is better. The current test of non-obviousness should be overhauled so that it is actually effective in testing whether something is obvious. That test is supposed to be measured by whether a person of average skill working in the field would think it’s obvious, so I propose that we actually ask them!

Patents need peer review. The current oversight is for patents to go to court and for judges to decide what stands, but as we’ve seen in the Sega case, there is far too much incentive to keep these cases out of court. Oversight should come before the patent is awarded, during a public review period during which anyone can point out the fallacies of pending patents. This would mean that anyone who applies for a patent and is rejected would not be able to keep their idea as a trade secret.

Some would call this a problem, but I think it’s worth it on the whole. Legitimate patent applicants would have to carefully consider the risks of applying, but a public review would hopefully help demonstrate that legitimate patents are, in fact, legitimate. Public review would also eviscerate what I’m guessing is the majority of patent applications, and rightly so. Reducing the number of patents granted each year by 90% sounds about right. And while we’re at it, only certain types of patents should have a twenty-year reach.

After a patent is granted, more oversight is needed as well. Currently, the only recourse is the courts, but a firm (or individual) should be able to challenge a new patent and get re-review, perhaps within six months of the patent’s approval. The fees from these challenges can go towards the funding of the Patent Office, which will admittedly need more federal funding as well, once the approval rate of patents is slashed by 90%.

Open review of patents does have problems, but secret review of patents with no appeal has already thoroughly demonstrated itself to be broken. We could do worse than a little more oversight and transparency in decision-making.

"Other people have invented almost everything already. It becomes more and more dffficult every day."

—Henrik Ibsen, 'The Wild Duck'.

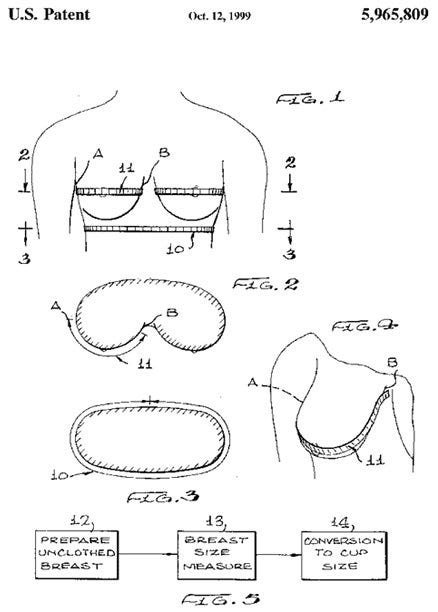

The joke’s on Commissioner Duell, because he should have realized that amazing inventions like 1-Click buy and the method for measuring breasts with a tape measure were yet to be patented in his time.

Method of Bra Size Determination by Direct Measurement of the Breast

"A method of direct measurement to determine cup size of the breast which includes band size measurement by initially measuring the user's chest or torso circumference with a flexible tape measure immediately below the breasts followed by the step of adding five inches to the measured number and incorporating conventional rounding-off procedures."

References

http://www.itjungle.com/tfh/tfh011606-story03.html

IBM stuff

http://www.stephenrubin.com/violation.html

The article that started it all.

http://www.around.com/patent.html

Very good article. Note that I took the images and captions of the two silly patents from this site. Maybe this is bad form, but the stuff is public record, so I don’t know.

http://www.ladas.com/Patents/USPatentHistory.html

http://infolab.stanford.edu/~ullman/pub/focs00.html

Source that talks about the paradox of getting a patent based on a particular implementation, but then being able to stop all other implementations in court.

Some sketchy info I used to estimate the Cracker Jacks sold per year at Dodger Stadium.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like