Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Thomas Was Alone is a game about colored rectangles learning about their humanity through companionship that was able to tug on plenty of heartstrings, but how?

My college freshman creative writing teacher would often stress the importance between writing that tells its reader something and writing that shows its reader something, and that writing that shows its reader something will often leave them much more satisfied than writing that only tells.

Having a free weekend, I decided to sit down and start churning away at my stack of games I accumulated over the Steam Summer Sale, starting with Mike Bithell’s Thomas Was Alone. The game has received much acclaim for its minimalist feel without coming off as low budget, but where the game truly shines, in my opinion, is in the story. Through narration by telling, the player is allowed to fill in the blanks in a way that creates an incredibly satisfying experience and makes character attachment inevitable.

Before delving into Thomas, it may be best to go back to that freshman creative writing class and briefly discuss story, plot, and the difference between the two. A work’s story is the chronological order of events that have happened leading up to the present, whereas its plot is the order in which the viewer is subjected to these series of events. Story is also concerned with events that are implied, but not explicitly stated, and it is here that Thomas’ narrative model truly shines.

The game’s plot at this point would only consist of a couple lines of narration and then whatever actions it would take to solve the level, but with those few lines, the narrator is able to bring the implied story of Thomas and Chris’ interaction to the front of the player’s mind. They are left to imagine the conversations between the naïve Thomas and already jaded Chris as the two progress together and develop in a way specifically tailored to the player’s imagination, making attachment all the more easy.

Thomas’ narration also serves as a subtle way to help players should they ever become stuck on one of the levels. By giving this advice through narration as opposed to say, a quest/tutorial objective, the player does not feel talked down to. The screenshot above was from a particular level I was being stubborn about, insisting that Thomas could make a jump that he really couldn’t. Eventually, with the narrator’s voice playing in the back of my mind, I realized that the puzzle did require Sarah’s help. When a player is struggling and help is needed, the narrator is there to do so, but otherwise they just remain a part of the story.

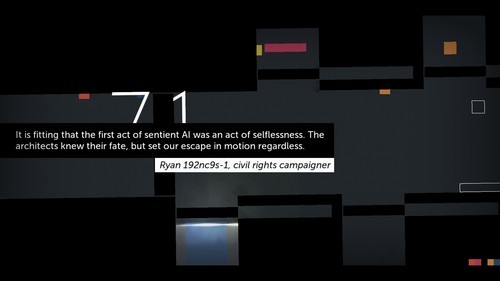

But the narrator isn’t the only method of storytelling in Thomas. Between “worlds”, bits of what seems to be an interview are shown. The interviews are set after the events the player witnesses, and while they do serve as reflections on the story, they also give the player a glimpse of what will be the repercussions of Thomas and friends’ actions. To me, these tidbits pulled double duty in finding closure for the story, but also giving us enough of a trajectory to be able to predict what will happen beyond the scope of the game so that we can watch the end credits feeling satisfied; a refreshing change of pace indeed for an industry that can sometimes get too focused on stretching the plot via sequels rather than telling a story.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like