Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Australia's game industry is building momentum, but not without stumbles.

Video games are fast becoming one of Australia's most recognizable exports. In recent years, a stream of titles born down under have found commercial success and critical acclaim on the global stage. Cult of the Lamb. Untitled Goose Game. Stray Gods. Heavenly Bodies. Hollow Knight. The Artful Escape. Gubbins. Unpacking. The list goes on and on.

Those projects are the work of a burgeoning development industry that many in the country feel continues to punch above its weight. Game Developer travelled to Melbourne for GCAP 2023 and PAX Australia earlier this year to learn more about the people making games in the region and the advocacy groups supporting them.

It was a trip that shed a light on the highs and lows that come with making video games in a country that (like many others) saw its creative industry decimated by the global financial crisis of 2007, but has since attempted to use the road to recovery as pathway to something even better.

Before we plow ahead, it's important to understand where the Australian video game industry is situated right now. A snapshot published by Australian games industry association IGEA in June 2023 states the games industry delivered $4.21 billion AUD in consumer sales during 2022, representing a 5 percent upswing on 2021.

IGEA CEO Ron Curry said that number is evidence of a strong retail distribution base and a population that "loves playing games," adding it was "no surprise" that sales exceeded $4 billion. "The added benefit is that the consumer demand for games in Australia and internationally allows Australia to build a substantial video game development industry," he stated.

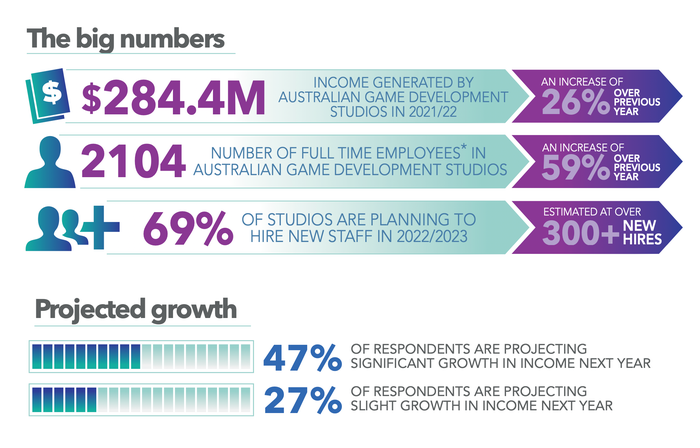

To build a "substantial" development industry, however, you need to persuade creatives and studios of all shapes and sizes to back your cause. The most recent Australian Game Development Survey suggests there's room for optimism in that regard. The report, again published by IGEA, shows that income generated by Australian game development studios during FY21/22 increased by 26 percent year-on-year to $284.4 million.

Image via IGEA

The number of full time employees in Australian game development studios also rose by 59 percent to 2104 workers over the same period, while the number of studios who said they planned on hiring staff in 2022/2023 totalled 69 percent. Notably, 85 percent of respondents said they are currently developing their own IP.

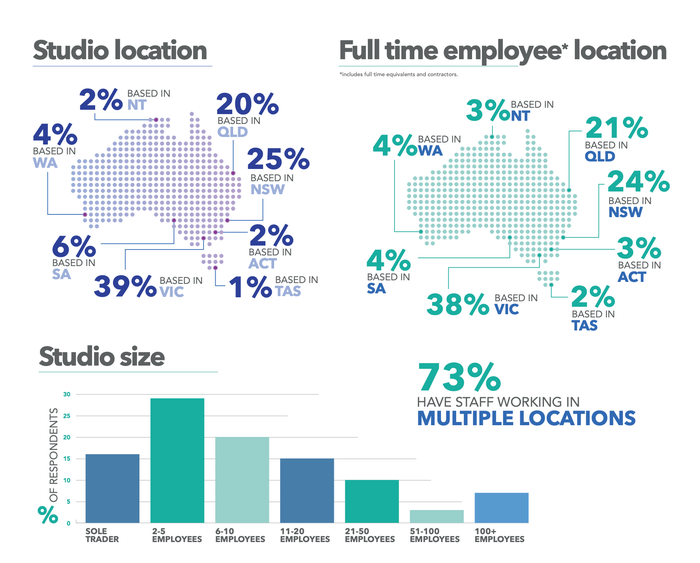

The report also highlights some disparity. The vast majority of studios, for instance, are based in the state of Victoria (39 percent) and New South Wales (25 percent), with IGEA attributing that regional imbalance to "the long history of recognition and support received from the Victorian government."

The bulk of studios in the country are operated by teams comprising 20 employees or less. For instance, only 10 percent of studios in Australia currently employ over 50 people, with the vast majority (64 percent) having less than 10 employees.

Image via IGEA

Government-backed funding programs are being deployed and reshaped to help those developers level up. During our visit, Screen Australia introduced three new initiatives targeted at indies, including an Emerging Gamemakers Fund specifically for teams working on smaller scale projects and a Future Leaders Delegation program aimed at getting five developers to GDC 2024.

Existing programs include the Digital Games Tax Offset (DGTO), which is part of the Australian government's 'Revive' national cultural policy and provides eligible game developers with a 30 percent refundable tax offset capped at $20 million per company. Local funding is also available on a regional basis through organizations like VicScreen–the Victorian Government’s creative and economic screen development agency.

From the outside looking in, it seems like the Australian industry is driving forward and has already taken some huge strides in firming up the support structures needed for future growth. Progress, though, should be perpetual. So what happens now?

"There has been an extraordinary evolution over a period of time, but I wouldn't necessarily call it revolution," says VicScreen CEO, Caroline Pitcher, explaining how the Australian industry emerged from the rubble of the GFC to rebuild.

"The industry in Victoria and Australia changed radically [after the crash]. That's when the triple-A global studios pulled out of Australia and we were left with a base of highly creative, incredible game developers that decided to stick with it and bring out their weird and wonderful ideas."

The decision by major studios to leave Australia was hardly ideal, but Pitcher suggests the silver lining was that it enabled local creators to "seize the gift of that moment" and take ownership of their destiny. "[We were given] the ability to really own Victorian and Australian ingenuity in our own ideas, our own concepts, and our own stories," she adds.

For its part, VicScreen has attempted to nurture creatives in Victoria by embracing the development community and spring-boarding them onto the international stage. As we mentioned earlier, funding is a part of that process, but VicScreen is also organizing events such as Play Now Melbourne, which is designed to connect local talent with publishers that have serious clout.

Image via VicScreen

Pitcher suggests that VicScreen's success has other Australian states and territories looking to the group for leadership, but notes that one of the biggest challenges facing any organization keen to support games lies in "articulating the story of value to government about screen holistically, and what that brings in its fullest form."

"It is culture. It is creativity. It is technology. It is skills. It is employment, and it's employment of young people. It's also the fact that that those employees are so incredibly future proofed with those skills," continues Pitcher. "This is the future and the government are catching on. But I have to say the Victorian government caught on a long time ago."

There are also more practical challenges. VicScreen games and interactive coordinator, Lise Leitner, believes there's room for improvement where funding is concerned, especially when it comes to financing prototypes. Discussing how VicScreen tailoring its own approach, Leitner says the group is eager to offer pragmatic advice that'll ultimately allow developers to "tell their story"

"We have a super robust assessment process where we will go to an industry panel. If it's not approved for funding straightaway, you can get feedback. So that's a huge learning opportunity," they say. "It's just about giving people the opportunity to come through, maybe get a little bit of money, and be in a better position to approach publishers."

They explain Cult of the Lamb, developed by Melbourne studio Massive Monster, is a great example of that process in action. VicScreen initially backed the studio with a small amount of funding somewhere in the region of $60,000, but that gold nugget enabled Massive Monster to add a bit more polish before reaching out to Devolver Digital and securing a publishing deal. The rest is history.

Cult of the Lamb has been a huge success for developer Massive Monster // Image via Massive Monster

Leitner says developers who secure funding though VicScreen won't need to make any repayments, and will crucially retain ownership of their IP. "It's really about getting the projects over the line. But then also, if somebody makes money through a project, they can put that into their next project. It's about creating that sustainability and affordability," they add.

No matter who you speak to about video games in Australia, it's clear the GFC weighs heavily on their mind. That's, perhaps, why the word "sustainability" is thrown around with such frequency–and given the current spate of mass layoffs sweeping across the games industry, it's easy to understand why.

"The global financial crisis decimated our industry here," says IGEA CEO, Ron Curry. "We had pretty much every publisher just pull out and it left a real hole in the market." Like Pitcher, Curry believes that chasm allowed Australia's smaller creators to shine, but with the industry expanding at pace it has also created a yawning talent gap.

"We lost a lot of talent," he says, noting that many veteran developers departed Australia to chase work in Canada and the United States. Some of those people never returned, and that's a huge issue when you're trying to encourage smaller studios to scale up and big businesses to settle down.

"We know that with the DGTO businesses are growing, but if you suddenly say 'we want a studio in Australia with 500 employees'–nobody in Australia works for a studio with that many people. So sometimes you have to import [senior level] people who can then act as accelerators for juniors and mid-level staff. But it's very hard to get into this country," says Curry.

The IGEA team including COO Raelene Knowles (centre) and CEO Ron Curry (far right) // Image via IGEA.

IGEA chief operating officer Raelene Knowles agrees. She believes that, on the whole, the Australian games industry is in a "healthy" place, but says that talent gap is making it difficult to establish clear pathways between smaller studios and larger companies. "I think Australia is quite famous for having great independent games, and that's brilliant–and we've got a couple of big studios, which is great," she says. "But how do we keep that middle functional? How do we how do we ensure the juniors coming through are getting adequate training and have adequate experience so they can spin off and do their own thing?"

Both Curry and Knowles suggest that bringing more triple-A studios to the region could be part of the solution, allowing those at the start of their development journey to amass valuable experience through mentorship schemes and junior roles that will prime them for success.

Curry says attracting global players like Ubisoft to Australia might involve incentives like a payroll tax or property offsets, but claims the benefit to local workers would help shore up the local industry.

"It would be great to have a couple of really big anchor developers [...] that don't go away," he says. "Have something like a PlaySide that has 500, 600, 700 people and a studio in each state. We've never really thought about that in Australia, but why can't we have that here? Then there's the next tier under that, and then there's the independents. But all of them would be existing in an ecosystem that's supportive of each other."

IGEA and VicScreen aren't alone in calling for more veteran talent. Developers themselves are feeling the effects of a skills gap that has left some newcomers in limbo and others feeling overwhelmed as they're pushed out of their creative comfort zones into executive roles–often out of necessity rather than choice.

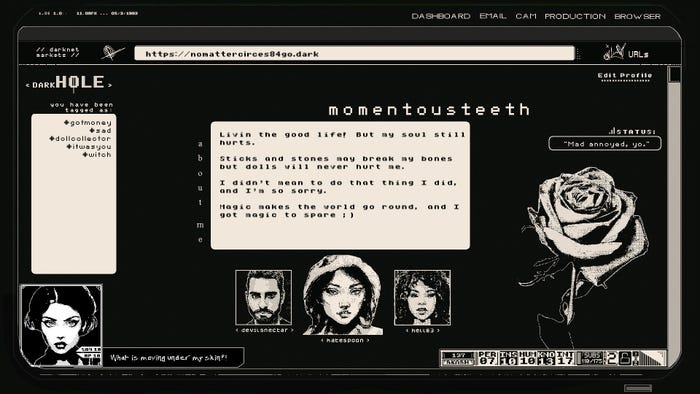

"This was definitely a creative project that wildly spun out of control," says darkwebstreamer lead developer Chantal Ryan. "I actually didn't mean to make a commercial game at all. This was one of my little creative projects that I was working on, but we had a huge response [...] and then all of a sudden we were getting messages from huge indie publishers."

That surge of interest soon turned Ryan from a "for fun" developer into the face of an indie studio that has been attending events around the world and negotiating with huge prospective partners. Although she quickly adapted, there's a sense more could be done to adequately prep developers for the trials and tribulations that come with building studios as well as video games.

"It's a weird adventure and you have to take things as they come, so it's never a linear path," she says. "Our path was literally 'oh, I'm making a game, but now people are trying to fund us.' Then it was 'oh, what's a pitch deck? Oh shit, I sent them the pitch deck and they want to talk money. Okay, now the government wants to send us to Gamescom but we need to be a company to do that. Now I'm applying to found a company what the fuck is going on right now? I'm an artist.'"

Chantal Ryan is currently working on psycho-horror RPG darkwebstreamer // Image via We Have Always Lived in the Forest

Others in the trenches share similar sentiments. Callum Williams, formerly an artist at recently shuttered Melbourne studio Samurai Punk, had become something of a senior figure after working at the studio for five years, but felt like they'd hit a brick wall when it came to skills progression.

"I feel like I've gotten to the point where I need advice from someone that's in the industry and who's a bit higher up and has that experience," he says. "When I first started our then art director Cyrian [Guillaume] had been there for a year and a half, but that was his first job. Initially he was teaching me a lot, but before he left we'd pretty much reached parity. Now he's left I'm the only artist, but there's still stuff that I could learn from someone senior above me."

Another developer, who chose to remain anonymous, claims it's almost "impossible" to find mid and senior level workers because "the industry is just too small at the moment."

"Australia is missing a key tentpole game(s) that draws talent to work here. What I mean is franchises or studios that are creative, large and inspirational," they say. "These works need to be Australian-owned and controlled for them to be lasting cultural artefacts. Attracting talent to work here is hard but retaining exist talent is even harder. This is not a silver bullet but it's not really discussed as a reason why people leave.

"All the major funding agencies need to be investing more in business training for new studio founders. We've had a lot of studios end up in situations where some shitty business stuff happens not because of malice, but purely because they don't know any better. The amount of people accidentally fucking over their contractors and employees is pretty upsetting. Most of us did arts degrees and are simply ignorant of better ways to run things that are both fair for workers and sustainable."

It's not just smaller studios feeling the squeeze, either. League of Geeks co-founders Ty Carey and Blake Mizzi, whose studio employed roughly 70 people at the time of our interview, explain that finding experienced devs in Australia has always been hard due to the "tyranny of distance," but hopes the DGTO will help attract more people and businesses to the country. Mizzi specifically believes talent is a "two-sided problem."

"In some ways, we're getting too many awesome graduates. They're incredible but we don't have the managers to support them," he says. "Then other studios have the managers, but you're working distributed like us. We have absolutely struggled supporting juniors. How do you train a junior when you're working remote through Zoom? It's hard."

The League of Geeks team // Image via League of Geeks

Mizzi suggests the solution will require advocates and the government itself to play an "insurance game." It's imperative, he says, that companies setting up shop in Australia are given the space and security needed to expand, and notes it's a challenge for mid-sized studios like League of Geeks to "succeed and thrive." Longevity is the key to expanding Australia's talent pool, he suggests, because it will provide the country's workforce with the time needed to acquire key skills.

Both Carey and Mizzi acknowledge that local and federal government are showing a lot of support right now, but like Ryan before, suggest there are some critical blind spots that need addressing.

"There used to be a program called Screen Business Ventures, which didn't invest in projects but invested in companies to build out their C-suites by maybe helping them hire a CFO. You know, how many studios have a founder that's also the lead programmer and accountant?" He believes that New Zealand is actually leading the charge there, and claims Kiwi studios "have much better business acumen–so we need to skill up on the business side in Australia."

Funding also remains a point of contention. The general consensus is that financing has improved thanks to the efforts of organizations like IGEA and VicScreen, but the country as a whole–while definitely in the ascendency–isn't quite where it needs to be.

A studio founder who wishes to remain anonymous believes the DGTO minimum spend threshold of $500,000 is an area that needs rethinking. "There are some incredible teams making some great games, many of which will be break out successes like Cult of the Lamb. The DGTO is certainly making things move in the right direction, even if it did have a bit of a spluttering start getting the final legislation through the halls of Canberra," they said.

"Because of the $500,000 threshold we'll probably see some of the bigger studios get bigger quicker, but some of the small-mid studios may still struggle a bit as try to raise that initial $500,000. VicScreen and Screen Australia investment helps there, but still may be a bit too far for some. If they lowered that threshold, that would help out a few more smaller teams for sure."

They also suggest advocacy groups like IGEA and VicScreen could be doing more to spotlight the work of smaller teams and studios that aren't producing global hits, but acknowledge the impact those organizations have had on the industry is overwhelmingly positive.

"Where the [advocates] fall short sometimes is being caught up in their own bureaucracy, and their desire to look good to other government departments as there's a bit of competition between States. They're desperate to say 'we helped funded X hit game' and milk that, which I can understand to a point, but it does mean that only the top tier successes get that extra visibility boost," they add.

There are plenty of challenges unique to Australia, but there are others that have unfortunately become commonplace across the industry. Since visiting Melbourne in October this year, two local indie studios have taken critical hits.

Killbug developer Samurai Punk closed its doors after over a decade and Jumplight Odyssey maker League of Geeks made over 50 percent of its workforce redundant after failing to clear a funding gap that emerged after multiple investment deals collapsed in quick succession. The industry at large is struggling right now, and no amount of optimism or moonshot visions of the future can shield people from the brutal reality of development in 2023.

One anonymous developer told us that Australian games are on an "upward trajectory," but suggested the industry might not be quite as stable as the marketing implies. What was evident during our time in Australia, however, was the genuine sense of collective camaraderie that permeates the development community. "It's like a family," adds Mizzi, discussing how the scene in Melbourne, specifically, has grown over the years. "We weren't in competition. There was genuine support."

It was a sentiment that was shared, sometimes verbatim, by almost everyone we encountered. "Everyone looks out for each other," explains darkwebstreamer developer Chantal Ryan. "We're constantly in each others DMs, asking questions and answering questions. Everybody wants to share what they know."

The challenge now is for advocacy groups like VicScreen, Creative Victoria, and IGEA to help the people who put Australia back on the map weather the storm. There are developers in Australia who need more assistance, and it's down to those institutions to help them secure that lifeline.

If the Australian industry can navigate some choppy waters, VicScreen CEO Caroline Pitcher believes it could very well become one of the "top five destinations" for creatives and prove it's possible to deliver sustainable, multi-project indie development at scale. Her colleague, Lise Leitner, says getting there will require more hard work and support for teams of all shapes and sizes, allowing emerging studios to complete production cycles without feeling pressured to deliver a global hit.

Indeed, it's vital to remember (perhaps now more than ever) that progress isn't defined by shimmering awards, lucrative franchising deals, or grandiose marketing campaigns, but rather the quiet victory of survival and the chance to start again. Art can only flourish if you back the people who make it–through both success and failure.

Game Developer was invited to GCAP and Melbourne International Games Week by Creative Victoria, which covered flights and accommodation.

You May Also Like