Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Procedural Generation (PCG) is a really abused marketing word. More often than not, PCG is used a surrogate for good game design. We fill our games of meaningless "variations" instead of meaningful "variety". It is time to stop this.

Last year, during the spectacular failure of a super-anticipated game such as No Man's Sky, I wrote an article on my blog on the big problem of Procedural Content Generation (PCG) used as a marketing tool. Today, I'd like to cover again the topic on a broader audience because I think the problem is still not solved.

Main problem is that PCG is a very overused marketing term. We all know games claiming that “in this game you can explore a gazillion different levels!”, “you can visit thousands millions of new world” and stuff like that. We all hear those phrases in the advertising material of every PCG-powered games.

For people like me, deeply invested in PCG for passion and research, it is clear the real meaning of those phrases. But for the average player, they build totally unrealistic expectations. When I read that a game offers 1000000 different worlds, I know that this means “10 variations for 6 different parameters, most of which are similar to each other or partly broken”. However, for the average player, this means exactly 1000000 different worlds! It is not surprising that the player’s expectations are never met!

What I perceive as "variation" are perceived by the final player as "variety". Unfortunately, these are two very different terms.

The problem here is about the meaning of the world “different”. Even if, technically, 10 variations for 6 parameters are technically different from each other, they are not “different” in the human brain. Without entering in the realm of heavy math and philosophy, we can simply say that two things are “Real Different” from each other if and only if their difference is greater than the stool threshold.

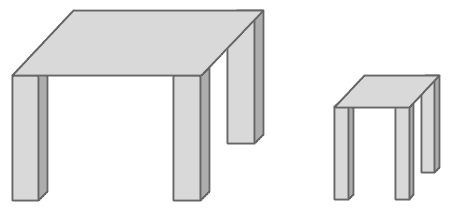

But what is this stool threshold? I will try to explain it with an example. Imagine you have an algorithm to procedurally generate different four-legged furniture. In this algorithm we can randomize three parameters, the two sizes of the rectangular plane and the length of the four legs. As you can imagine, we can generate a lot of tables, however, if the legs are tall enough and the plane is small enough, we stop having a table, and we have a stool instead. Well, the Stool Threshold is exactly the blurry line that separates the stools from the tables.

As you can see, this is not a formal definition. But it can give us the idea of what “noticeably different” means. It is not based only on how the table/stool looks like, but this should take into account also its purpose (that is, we use a table in a completely different way than a stool). So, even if we technically have thousands of different furniture, in the end, we are offering to the players just a bunch of similar tables and stools. That’s exactly why people get hyped and bored by PCG-centered games: you promise thousands when you are offering just 2.

There are two advice I can give you to avoid the PCG-marketing trap. If you avoid the lazy applications of PCG, you will find that it will serve you in a much deeper way than you think.

Stop using PCG to replace actual game-play! PCG is the palette, it is not the real painting. PCG is a tool that helps the gameplay, it is not The Gameplay. If the game-play is based exclusively on watching PCG at work, you are in a very dangerous place.

Aim to the meaningful, not to the different. PCG is not always based on generating billions of different things. Instead of generating vibrant worlds that then will be static for the whole duration of the game-play experience, use PCG to follow the player during the game, providing dynamism and changing the world in such a way the player can feel an emotive attachment. An example I love is how in Dwarf Fortress the dwarfs can use earlier events lived by the player to craft artifacts, and books. A jar inscribed with the events in which your beloved dwarf almost killed all your expedition is much much more interesting than a stunning but completely random and abstract jar.

And if you cannot really avoid that, at least stop using PCG pure numbers as a marketing slug in your trailers.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like