Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

“The SNES was the golden age of pixel art," says Eric Barone, creator of Stardew Valley. "It had enough complexity to look interesting, but was limited enough that you had to be creative with it."

In 1991, the gap between what was possible at home and what was possible in the still-relevant arcades was narrowing. Early arcade games often relied on abstract concepts and symbols to create compelling action: that triangle is an asteroid-shooting starship; that horizontal bar is an agile tennis player. The Sega Genesis found fast success with ports of more advanced arcade hits like Altered Beast.

But this next generation of machines would not be confined to mere mimicry; with the release of the Super Nintendo 25 years ago this month, games designed from the ground up for home consoles would change our expectations of what was possible and deliver on the promise of richer, more immersive experiences. We felt this most immediately in the striking visuals; over time, a number of distinct styles would emerge as aesthetics.

Compared to machines released during the Reagan era, the SNES was capable of an explosion of colors: 32,768 all told, 256 at once. A technique marketed as “Mode 7” allowed developers to enable a kind of pseudo-3D by rotating and scaling sprites.

Different materials could be approximated: this looks like molded clay, that looks like a child’s scrawled crayon. Later advancements made possible visuals built on Silicon Graphics workstations along with true polygonal graphics. Now you could build entire vehicles out of triangles and spin them around as full 3D objects.

Looking back, Super Nintendo games may look simplistic or rudimentary. But at the time, the SNES allowed artists to bring their visions to life, and players swooned to never-before-seen vistas. Many of those players grew up to develop games themselves, and the impact of the SNES is evident in their work.

We talked to many of today’s game creators about the aesthetics of the Super Nintendo, and how that machine helped shape a generation of play.

***

If today’s games strive for photorealism, then the Super Nintendo was the pinnacle of pixelated Pointillism. Just look at the image from Chrono Trigger [above]. Each pixel was a small dot of color that, when combined, formed something richer and greater than the sum of its parts--especially when viewed on the lower-resolution CRT televisions of yesteryear.

“In my opinion, the SNES was the golden age of pixel art. It had enough complexity to look interesting, but was limited enough that you had to be creative with it. There's a certain sweet spot for pixel art... too low-res and it's ugly, too high-res and it's not even pixel art. The SNES, to me, struck the perfect balance between those two extremes.” - Eric Barone, ConcernedApe (Stardew Valley)

Harvest Moon

“It seems as though "Final Fantasy + pixel art" has become synonymous of the aesthetic identity of the SNES...any time an overhead game looks beautiful and has pixel art, people think about Final Fantasy, even if said game is nothing like Final Fantasy.” - T. J. Thomas, alpha six productions(Joylancer)

Secret of Mana

“In childhood, when I played pixel-art games, it wasn’t “pixel-art”, it was just “art”. I couldn’t imagine these screens would ever look more beautiful or detailed, because just like everyone else, I was interpolating the pixels as I watched. I was adding in detail that wasn’t there.” - Rex Crowle, ex-Media Molecule, FoamSword (LittleBigPlanet, Tearaway, Knights & Bikes)

What began as a simple trick to approximate three dimensional space in a 2D-based system became a visual hallmark of the SNES and a key differentiating factor in the fight against Sega. Some games used the sprite-rotation with subtle elegance (Final Fantasy III opening); others poured it on thick (NHL Stanley Cup).

“Seeing the Mode 7 effect for the first-time (and every time afterwards) was incredible. It was just so digital and futuristic. When the Mode7 kicked in and screens started scaling and zooming, it was like the console was transcending reality!” - Rex Crowle

ActRaiser

“SNES games would rotate and scale anything and everything, without regard for how blocky and pixelated stuff got. We didn't know to care back then. It was just amazing to behold.” - Tom Happ, (Axiom Verge)

“When you are escaping [in Super Metroid] and the level tilts to and fro, that was a use of the system’s graphics that I thought was really ingenious.” - Chris Johnston, Adult Swim Games (Headlander, Pocket Mortys)

“I still play the original F-Zero now... The exhilarating thrill of speed and brilliant use of Mode 7 was like nothing I’d ever played before. Later iterations of the game introduced true 3D, and yet they never quite managed to reproduce the pure and simple elegance of the original pseudo 3D. - Phil Tossell, Nyamyam, Ltd. (Tengami)

Demon's Crest

NES characters and worlds were often simple enough to be recognizable with few details: Think of Ninja Gaiden’s Ryu cascading over the same repeating platforms, or Contra’s soldiers ambling through a monochrome jungle. But the SNES boasted big, bold figures traipsing through detailed vistas bursting with color.

“The NES and prior generations still required some use of your imagination to really get a feel for locations, but I think SNES took it to the next level where it was all there spelled out for you. Everything from the dark and slimy tunnels of Super Metroid to the realistic locales of Street Fighter II were able to be beautifully rendered on the SNES with its wide color palette.” - James Petruzzi, Bit Kid Inc. (Chasm)

“There was something about the palette that was used in Super Mario World and the fluidity of it that stuck out. I just stood there for ages staring at it, saying ‘Dad, Dad. I must have this.’” - Rhodri Broadbent, Dakko Dakko (Floating Cloud God Saves the Pilgrims, Scram Kitty and his Buddy on Rails)

“I always felt like it had a chunky look to it. Possibly because it had a resolution of 256 x 224 while the Genesis was 320x224? Also, the hardware has this limitation where the palette is divided into 16 parts with 16 colors each, and each tile or sprite can only select one. So you'll see a lot of images where all the rocks, say, are shaded with a ramp from light to dark grey, then the plants are all shaded with another ramp from light to dark green. Things would thus be ‘contained’ in separate parts, often following collision boundaries, in a way that feels almost tactile. It nets a different look than in later consoles where any color could go anywhere.” - Tom Happ

Zombies Ate My Neighbors

In the early 90s, game designers were still testing the boundaries of player expectation. There were no rules. Cue psychedelic boss fights, ravens rotating around the moon, and one giant baby.

“There's a certain ‘feel’ to the SNES that is kind of hard to describe, but that I've sought to capture in my own work. I guess it's a certain playfulness, or a feeling of being on the cusp of some great discovery, some great ocean of the imagination that you're only just dipping your little toe into.” - Eric Barone

Yoshi's Island

“With Yoshi’s Island, games really started to be stylistically more creative… we don’t have to stick with this linear progression into realism. We can be more out there in what we do.” - Rhodri Broadbent

Earthbound

“Earthbound uses a lot of interesting tricks... Especially at the end of the game. I think back in the day, people thought it looked like an NES game and didn’t buy it. They were right--it did look like an NES game, but it was an aesthetic choice.” - Chris Johnston

Donkey Kong Country

Along with pre-rendered graphics, these were the first steps away from hand-drawn art and toward the use of computers to build more photorealistic visuals. But when images built on Silicon Graphics workstations get down ported to the relatively underpowered SNES, certain sacrifices had to be made.

“Any sprite animations made from photography or pre-rendered CG was ridiculously called Digitized, and I couldn't get enough. Mortal Kombat, Clay Fighter, Donkey Kong Country... hell, even Pit Fighter was kind of cool. No, actually it sucked.” - Sean Krankel, Night School Studio (Oxenfree)

“I think Donkey Kong Country is important. Not because it’s a good game, because I don’t think it is a good game. But because of the graphical style and what they were trying to do. CD-ROM technology was so big and computer graphics were so big at the time, that having this pseudo rendered Donkey Kong with those visuals -- it looked like the future.” - Chris Johnston

“Donkey Kong Country had this radical new look. Pre-rendered graphics were a big deal at the time, and seeing the amount of color and view depth achieved in that game was mind-blowing for me. I was just starting to understand what it meant to make this look possible, how expensive it all was (the rigs were costly plus the time it took to render each frame was intense), and how different it looked from anything else that had come before. While it's a bit ugly now, I still recall intensely re-watching that pre-release VHS tape they sent Nintendo Power subscribers for the game. It was my first behind the scenes look at games development in video form.” - Alex Preston (Hyper Light Drifter)

“The 90's aesthetic was very bold and playful, and Donkey Kong Country captured that. Also, the soundtrack by David Wise is an enduring masterpiece.” - Eric Barone

“It made me sad when hand-drawn pixel-art started to be replaced with pre-rendered sprites at the very end of its era. Although there were extra details like more realistic shadowing, the art lost its crisp styling, where every pixel was carefully considered by the artist clicking their mouse, like a sculptor tapping on their chisel.” - Rex Crowle

Though the full transition from 2D to 3D games would happen with the coming Sony PlayStation, we first saw evidence of the shift on the SNES with the pioneering work of Argonaut Games and a young programmer named Dylan Cuthbert. Here, he explains how they first got the sprite-based super machine to punch above its weight and spit out the necessary polygons for Star Fox.

“One of the reasons the FX chip and Star Fox got made was because I had knocked up a 3D game on the Gameboy [X]--I was 18 at the time--and we had suddenly been flown over to Kyoto to meet with Miyamoto because they were struggling with 3D on their launch title Pilotwings. They showed us an early prototype and explained that they were using a DSP chip on the cartridge itself to help with some of the calculations but Miyamoto was frustrated that he couldn’t rotate the biplane in all directions without using up way too much sprite memory and drawing each frame individually."

"Jez [San, founder of Argonaut Software] had the idea of creating a custom chip to replace that DSP with much more powerful features such as polygon rasterisation. As luck would have it, Argonaut at the time had just finished working on prototypes for the Konix Multisystem, a console that didn’t make the light of day but had a bunch of pretty cool custom chips in it and we were close to the people who had made those chips, some of whom worked on the original ZX Spectrum. So Jez phoned Ben Cheese, who sadly passed away a few years back, directly from the corner of that meeting room and fleshed out the rough details of the chip, right there on the spot. This obviously took Nintendo by surprise and they set up meetings with Yamauchi. A few months later the project got going.” - Dylan Cuthbert, Q-Games

"While the polygonal look didn't make it into many games, it marked an important turning point in the industry in the push for new graphical technology.” - Alex Preston

“[Star Fox] felt so real in its physicality. It was as impactful as VR feels now.” - Sean Krankel

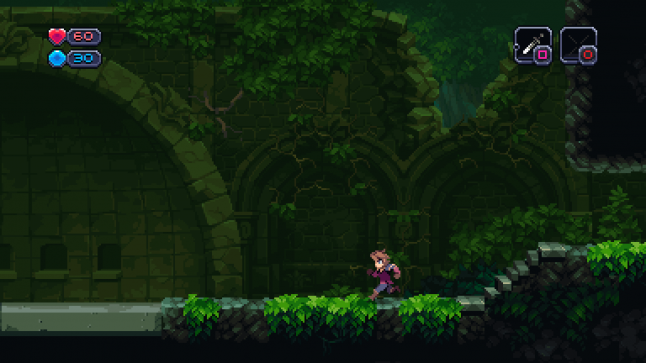

What’s old is new again. After years of trudging down the same brown corridors and staring over a gun barrel, the crisp 2D style found in classic SNES titles is coming back thanks to developers who grew up during the 16-bit era. But could these games actually run on the 1991 hardware?

“Stardew Valley has too many colors, and the music and sound effects are too complicated to work natively on the SNES. But I think a SNES version of the game could be theoretically possible and I wish it existed… I tried to capture the SNES style as much as possible without having it get in the way of good design and convenience for the player.”” - Eric Barone

“Chasm has a very low native resolution that could be run on a CRT (384x216), but the framework we use to develop it definitely could not run on the SNES. Keeping an authentic aesthetic to the period is very important to us though, so there’s certain things we don’t do like mix resolutions or use advanced lighting.” - James Petruzzi

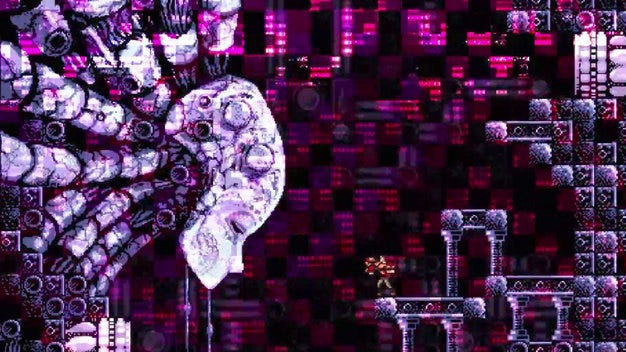

“The SNES supports more colors than Axiom Verge uses, but probably couldn't handle the amount of creatures, bullets, and explosions on screen at once. There are times when AV zooms out the whole screen to fit a boss or creature (such as Urukku) and I don't think this would work on SNES. And the soundtrack to AV is basically CD quality. You could probably rewrite the whole game in a way that would look and play similarly on SNES--kind of the way a lot of SNES games looked similar to the arcade but with graphical reductions.” - Tom Happ

You May Also Like