Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Many games claim to be co-op, but offer an experience where only one player is needed to beat the game, the other can simply “tag along.” The second player is effectively rendered superfluous and begs the question: How can we avoid this “tagalong trap?"

Originally posted on the Shadow Puppeteer development blog.

In this blog we’re going to look at cooperative games, and identify components that make them “true co-op games” where both players perform active and meaningful roles, as well as cite examples of how we implemented these components when designing Shadow Puppeteer.

Cooperative games challenge players to work together: To succeed or fail as a team as they strive to reach a common goal. In these games, players can have identical or differing abilities. As such, we will not be covering competitive or adversarial multiplayer titles like Street Fighter or Mario Kart.

The first recorded co-op game was Fire Truck [1978]. Fire Truck challenged one player to steer the front of a fire truck while the other maneuvered the rear. Examples of more recent co-op games include Monaco: What’s Yours is Mine and Portal 2.

But not all co-op games are created equal. Some co-ops are engaging, giving both players a sense of purpose, while others can cause frustration or apathy due to an imbalance in the distribution of skills to each player. So, what makes a good co-op experience? This was the central question Sarepta studio asked ourselves as we began development on Shadow Puppeteer. And to answer it, we examined co-op games throughout history to identify what makes a good co-op game deliver an unforgettable and unique experience.

Our analysis and internal discussions resulted in the identification of three components that we believe define what we call “true co-op games.”

Many co-op games offer players two ways to play the same version of the game: one that you can play by yourself, and another that you can play with another player. But unless all players are integral to the completion of the game, there can be limited incentive to cooperate.

For example, Little Big Planet has sections that you can only access and complete if you have the minimum required number of players. By comparison, the NES title Chip ‘n Dale Rescue Rangers can be played in both single player and co-op. In this example, the addition of another player makes the game become easier, making it more accessible to less skilled players.

Consider the difference between requiring and allowing two players.

Consider the difference between requiring and allowing two players.

Very often in co-op games, the two characters have identical roles or skills. This can result in players dividing tasks throughout the game between them to increase efficiency. This can also, and most often does, result in one character performing all major actions, while the second simply “tags along.”

A good example, of how different player skills can create an engaging co-op experience, is Trine 2. Players control three characters with different abilities: The wizard can cast spells that move or create objects, the thief can use a grapple or a bow and arrows, while the knight has superior fighting abilities and strength. Conversely, in Halo 3: ODST both players play an Orbital Drop Shock Trooper, and although they can choose to equip different weapons, each player's’ skills and abilities are identical.

Do your characters have the same skills and abilities inside the game, and how does that effect your co-op play?

Do your characters have the same skills and abilities inside the game, and how does that effect your co-op play?

A good co-op game should engage all players equally, i.e., avoid having one feel like a “sidekick.” Whether players have different or similar skills and abilities, it’s important that they both feel like active, contributing members.

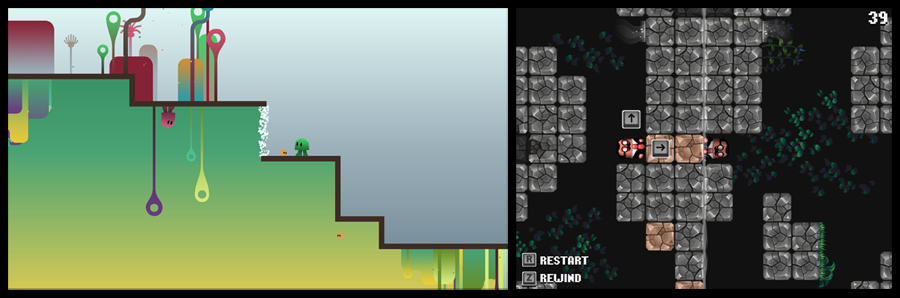

In Ibb & Obb both characters are presented as equals. The two can either move in the world above the ground with regular gravity, or use portals to walk upside down in the world below. They have similar skills and abilities, but some portals can only be used by specific characters. This ensures that both players take on an active role where they contribute. Both the path above and below offers challenges, and the players take turns having to perform important tasks in order for both to progress.

Another example of this is Paul & Percy. Unlike Ibb & Obb this game utilizes a switch mechanic between the two characters, which enables single player. Paul & Percy have the same abilities, but the characters are consistently separated on either side of screen. This means that the characters are always taking turns to move objects around their side to enable both to progress, creating a natural flow of “back and forth” gameplay.

Similar abilities can still provide agency for both characters when they are in separate locations.

Similar abilities can still provide agency for both characters when they are in separate locations.

After having examined co-op titles and assessed the properties of what made them fun and memorable, we turned to our own game, Shadow Puppeteer. How could we take the new knowledge we had acquired and apply it to the development of this game? Within the context of our concept, how could we ensure that we created a compelling experience dependent upon both character’s unique skills and participation?

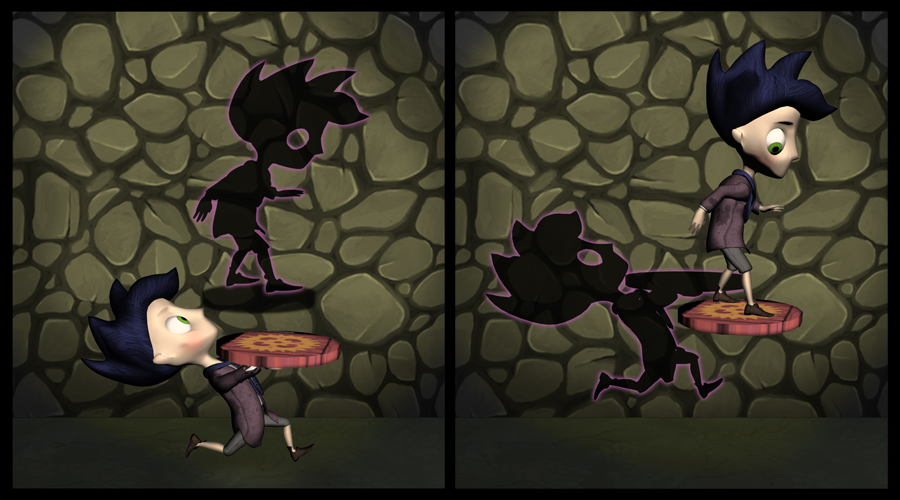

At the very core of Shadow Puppeteer lay the premise of a boy and his shadow, and the exploration of the idea of ‘what would happen if our shadow came alive’. How would the Boy and Shadow differ in how you played them? What similarities would they have, if any?

With our initial premise we were creating a situation that in itself made it necessary to have both players contribute in an active manner, by separating the two players in different “dimensions.” On character, the Boy, could operate in 3D space, while the other character, the Shadow, could exist in the 2D. And with this, we could create an internal logic in the game that communicated well to the players the unique value of each character, making it easy to understand why certain actions and places were accessible to one character and not the other.

The Boy and Shadow of Shadow Puppeteer.

The Boy and Shadow of Shadow Puppeteer.

Since Shadow Puppeteer would mix platforming and puzzle solving we decided that the characters would have certain similar abilities to perform core gameplay actions. They can both walk, run and jump. This also fits the narrative of the characters since both have the same origin (connected as human and shadow).

They also have common basic interaction skills: such as moving crates, pulling levers or carrying lids. The difference is that the Boy interacts with objects in the “real” world, whereas the Shadow interacts with the shadow of those objects. Doing this gave us the opportunity to make puzzles where part of the solution was figuring out who needed to interact with what. For example, having one object’s shadow cast within another shadow, makes it inaccessible to the Shadow character. Similarly, placing objects in the background or foreground can bring it into or out of the Boy’s reach.

The lid: An example of when both can use an item, but the result is different.

The lid: An example of when both can use an item, but the result is different.

In addition to sharing core gameplay abilities, the characters have unique skills. We altered the Shadow’s gravitational pull to make him drawn to the closest, strongest light source. This would enable the Shadow to reach new places within levels. This could have been a mechanic that made the Shadow significantly more active than the Boy, but instead it balanced the two characters out: The Boy already had an additional platforming element by being able to move in the third dimension. Source change would be the Shadow’s response to that. The characters also have a skill dependent upon another: The Boy can create different shadow tools with his lantern, that the Shadow can pick up and use. Making this mechanic of creating and using shadow tools a joint effort makes players communicate and work closer together.

Each character had to be equally important with the same amount of tasks to do. This was implemented with the two other central co-op components through the game’s level design. As an example: let’s look at an early level called “Home.”

The players have witnessed the Shadow Puppeteer stealing all the other shadows. They have been introduced to core gameplay mechanics: moving, jumping and activating interactive objects. Here, the players start off meeting the Puppeteer, who becomes unexpectedly diminished as the handle of his musical instrument breaks, leaving him without his weapon. The Puppeteer runs and the players are faced with their first true co-op challenge.

The Boy can climb the ladder, but how will the Shadow progress?

The Boy can climb the ladder, but how will the Shadow progress?

The Boy can progress through the first section of the level by climbing a ladder. However, the ladder only exists in the 3D world, which is unaccessible to the Shadow, blocking his advance. The differences in the characters’ abilities creates a situation where they must consider how to use each other’s situational strengths to compensate for each other's weaknesses. To help the Shadow progress, the Boy must pull a crate from the shadows into the light in order to create a platform for the Shadow cast by the crate.

Which of the characters can get up to the next landing?

Which of the characters can get up to the next landing?

But at the next stage the shoe is on the other foot. A tree branch in the foreground is casting a shadow, creating a platform to the next landing. The Shadow can easily use the branch’s shadow to advance. But, the Boy can’t jump on a thin branch in the foreground then jump to the landing in the background. The Shadow must jump up, push the shadow of the crate, so the actual crate falls to create a platform for the Boy. The “first one, then the other” nature of this play creates a dynamic that emphasizes the importance and dependency of both players and balances the amount they have to do so their involvement feels equal.

Cooperation through assistance.

Cooperation through assistance.

Creating an engaging co-op experience comes down to carefully understanding the roles the characters play, and balancing their involvement throughout the experience. It is an iterative process, where you’re constantly assessing whether you’re achieving your goals with the current mechanics and level design. Remember, a co-op game is nothing without players, so it’s important to test often and make sure each player is feeling engaged.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like