Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

An international line-up of indie developers was brought together by the IGDA Switzerland Chapter to discuss the topic of death and consequence in game design. What emerged were varied perspectives that reflected the complex nature of death.

The IGDA Switzerland Chapter hosted its second themed Demo Night in Lausanne on Wednesday 10th August (you can read about the first music themed event here). The event focussed on the theme of ‘death and consequence’ in game design, and was hosted in collaboration with the Game Developers Suisse Romande meet-up with generous support from the Swiss Arts Council, Pro Helvetia, and the Swiss Game Developers Association (SGDA). An international line-up of developers was invited to share its perspective of death in games and explore how this much theorised design element has evolved from a benign consequence of losing during gameplay.

The evening’s line-up was composed of special guests, co-director of That Dragon, Cancer (2016), Josh Larson; prolific game designer and academic, Pippin Barr; and Attila Szantner, CEO and Cofounder of Geneva-based Massively Multiplayer Online Science (MMOS)—the developer behind Project Discovery, which is integrated into EVE ONLINE (2003) by CCP Games. Switzerland’s indie community was represented by Philomena Schwab who talked about Niche: A Genetics Survival Game by Team Niche; Elias Farhan presented Splash Blast Panic by Team KwaKwa; and David Javet discussed Stonebond: The Gargoyle’s Domain.

Each presenter was asked the same set of questions to allow the audience to make easy comparisons:

How many times does death occur in your game?

What is the player's intended experience of death (fun, tragic, irritating, etc.)?

What are the principal game mechanics for creating these experiences?

What are the lasting consequences to players as a result of death in your game?

Please note that this article is more a dissertation than a straightforward write-up of the event, and features supplementary material to emphasise certain concepts.

The first presenter was Josh Larson who Skyped-in from Des Moines, USA, to talk about That Dragon, Cancer —an award-winning and critically acclaimed game created by Josh, Amy and Ryan Green, and a small team under the name Numinous Games. That Dragon, Cancer is based on Amy and Ryan Greens autobiographical experience of raising their son, Joel, who was diagnosed with terminal cancer at the age of twelve months. Joel was only given a short time to live, but continued to survive for four more years before eventually succumbing to the cancer in March 2014.

While black cancerous forms scattered throughout the game at regular intervals serve to visualise the family’s threat, death only occurs once in That Dragon, Cancer and it’s a deeply harrowing experience. The development team set out to create a universal story that goes beyond the experiences of the Greens’—relatable to every player’s experience of loss. Josh kindly shared his personal experience of losing a loved one to illustrate that such sad situations can also contain moments of positivity—much like a tragicomedy that offers humour to offset an emotionally oppressive situation. For instance, thinking of a loved one can trigger the memory of a funny situation. Josh also highlighted that people deal with death in different ways. Players of That Dragon, Cancer find that Amy remains doggedly optimistic while Ryan’s tendency is to confront the facts—often withdrawing into an empty space of contemplation.

That Dragon, Cancer (2016), by Numinous Games, presents players with a sequence of varied gameplay vignettes that explore every facet of dealing with death—from moments of optimism and joy (left) to withdrawal and sorrow (right).

Conveying such multifaceted experience of death would not be possible if Josh and the team had focussed on one core gameplay mechanic—as is typical in most video games. That Dragon, Cancer is therefore composed of a sequence of gameplay vignettes that explore the emotionally complex nature of losing a loved one. Fleeting moments of happiness, triumph and optimism are contrasted with moments of sorrow and reflection using gameplay mechanics to convey each aesthetic. For example, a Mario Kart-style driving sequence (above left) elicits joyous activity from players but is contrasted by moments of relative stillness when players are tasked with exploring a desolate hospital or find Ryan adrift in an emotional abyss (above right).

Each gameplay vignette works in combination with the whole to create a poignant reflection on death. Without wishing to give too much away about the game’s ending, players are offered an interactive space in which they can dwell for as long as they wish to express themselves and vent their feelings.

The lasting consequences to players of That Dragon, Cancer is a very real confrontation with mortality and the transitory nature of life. Josh found a particularly heart-warming discussion forum in an unlikely place: the comments section of a That Dragon, Cancer “let’s play” YouTube video. What was surprising—other than the uncharacteristically amiable comments—was that users were talking openly about their personal experiences with cancer. It seems that That Dragon, Cancer gives people the confidence to speak about a topic that is somewhat of a taboo (in the U.S., at least). This is an achievement that the video games industry should celebrate.

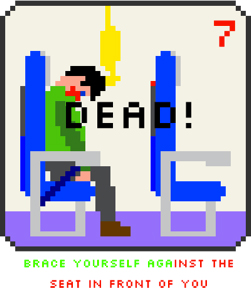

Safety Instructions (2011), by Pippin Barr, takes a whimsical look at death in video games by encouraging players to experience the various ways that a passenger can die in an airline accident.

Pippin Barr was the second presenter of the evening—Skyping-in from Montreal, Canada, to talk about his portfolio of interactive commentary on death in games. Pippin is well-known for creating games that reflect on the nature of games—such as the recently released Game Studies (2016), which he developed together Jonathan Lessard to lampoon five game design theories.

The first game that Pippin presented was Safety Instructions (2011). Inspired by Sierra Nevada titles like the Space Quest and the Leisure Suit Larry series, Pippin’s game encourages players to blunder through inflight safety instructions and cause the on-screen airplane passenger to suffer a multitude of whimsically presented deaths. Pippin stated self-deprecatingly that this was “the last fun game [he] made.” In stark contrast to That Dragon, Cancer presented by Josh, Safety Instructions is an explicit reference to the carefree treatment of death in the majority of video games. Death can occur an infinite number of times with repetition: the player passenger can explicitly die in 9 unique ways; two other people can die according to the player’s actions; and there are two ambiguous endings that allude to a watery end. The player’s takeaway is pure entertainment.

A Series of Gunshots (2015), by Pippin Barr, solicits players to user their imaginations and evoke personal images of murder.

A Series of Gunshots (2015)—created four years after Safety Instructions—saw Pippin return to the theme of death, albeit with a significantly more serious tone matched by the sombre colour palette of the game’s visuals. A Series of Gunshots features five scenes in a play-through and players can fire 1-3 gunshots in each scene. Death is not explicitly represented in the game. Only muzzle flashes can be glimpsed through windows. The reasoning behind these game design decisions is to create a life-like representation of death by evoking the act of murder in the players’ imagination after they’ve pulled the trigger. The possibility to fire 1-3 gunshots has a performative function that further nourishes the players’ imagination, since one shot fired will stir-up different imaginings to three successive blasts.

The final design element that affirms A Series of Gunshots’s intentions as a commentary on the real repercussions of death is that the game installs a browser cookie that can prevent players from replaying the game successively and experiencing everything anew. In opposition to the whimsical approach of Safety Instructions—where death could be replayed an infinite number of times—Pippin’s A Series of Gunshots (and That Dragon, Cancer presented by Josh) leaves players with a realistic sense of finality. How fluidly and quickly players can restart a game—if at all possible—is an important design consideration that can elevate or lower the emotional value of death.

Jostle Parent (2015), by Pippin Barr, features colourful Atari-style graphics that influenced players’ perception of the game’s seriousness.

In Jostle Parent (2015), Pippin continued his exploration of “proper tragedy” by tasking players with the survival of three children. A total of four deaths can occur in the game: the three children and the playable character. Inspired by Jostle Bastard (2013)—a game created by Pippin in 2013—Jostle Parent attempts to escalate the emotional impact of death by “emphasising the tenuousness of the player's ability to act and help by limiting it to physical jostling of the children out of harm's way.”

An interesting point raised during the presentation was that Jostle Parent saw a return to the colourful palette of Safety Instructions—the first game presented by Pippin—after the sombre colours of A Series of Gunshots. The Atari-inspired aesthetic likely influenced how players perceived the serious intentions of the game, as stated by Pippin in Jostle Parent’s press kit:

“It isn't clear to me that the game succeeds in being genuinely tragic - I think a lot of people will still read it as slapstick comedy - but certainly the intent was for it to feel sad when a child dies during play, and especially sad if they all die.”

Death doesn’t occur in Independence, Missouri (2016), by Pippin Barr, but the game acknowledges the deaths of five people from The Oregon Trail (1971) on which it is based.

For Independence, Missouri (2016) Pippin went with a sombre colour palette once again, in part, due to design constraints, he explained. The game is based on two sources: the The Oregon Trail (1971) by Don Rawitsch, Bill Heinemann and Paul Dillenberger; and the classic Percy Bysshe Shelley poem, Ozymandias. The game acknowledges the deaths of five people when the game begins but the player cannot die.

The discussion turned focus away from Independence, Missouri’s towards the diversity of Pippin’s video game portfolio. Safety Instructions, A Series of Gunshots, Jostle Parent, and Independence, Missouri, mark only a handful of the games that he has created in recent years. But what’s particularly interesting is that each game approaches death from a unique perspective, which reflects Pippin's ongoing analyses of death in video games. More importantly, the games reflect the multifaceted nature of death that was discussed with Josh and the design of That Dragon, Cancer. The difference with Pippin’s work is that each game is a self-contained gameplay vignette. However, both approaches highlight that death cannot be conveyed with just one idea or gameplay mechanic. Death is a complex topic that is composed of many perspectives—each feeding the audience with layers of emotions and richness of ideas.

Attila Szantner, shifted the discussion on death and consequence to a real-world scientific level. Attila is the CEO and Cofounder of Geneva-based Massively Multiplayer Online Science (MMOS), which created Project Discovery—a mini-game integrated into EVE Online (2003) by CCP Games. No deaths occur within Project Discovery. Quite the opposite! Project Discovery is helping scientists to prevent deaths in the real world, which it does through citizen science (or crowd-sourced science) by enrolling the help of gamers to contribute to scientific research.

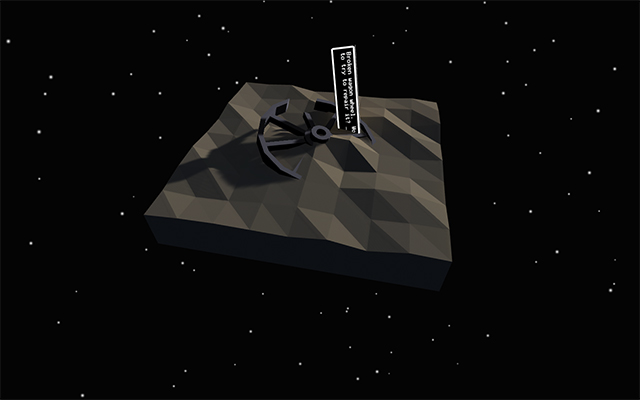

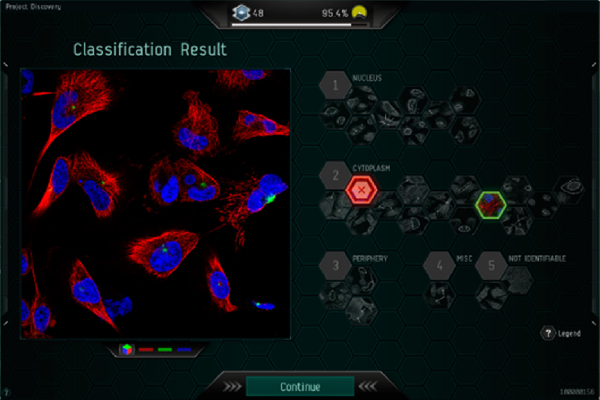

Project Discovery, by Massive Multiplayer Online Science, crowd-sources players of EVE Online, CCP Games, to help refine the cataloguing of proteins for science.

Atilla explained that developer, CCP Games, has expertly woven Project Discovery into the lore of the game’s universe with the purpose of making it meaningful. The story leads players to believe that they are working for the 'Sisters of EVE'—a religious humanitarian-aid organization, which rewards the participants’ efforts with virtual currency and the ability to purchase unique armour. What players are inadvertently doing by participating in Project Discovery is assisting with the Human Protein Atlas (HPA), a Swedish-run effort to catalogue proteins. The HPA’s website explains that proteins fulfil most functions in the body and their malfunction is a common cause of human disease, and the reason why most drugs target proteins. The project also includes the analyses and identification of cancer tissues. The aim of Project Discovery is to refine the HPA database that holds over thirteen million microscope images.

Atilla went on to explain that players of EVE Online can take timeout from the main game whenever they wish to play Project Discovery and help identify patterns of protein distribution in human cells using the gamified interface seen in the above image. The cells innards in each image have been color-coded: blue for the nucleus, red for microtubules and green for anywhere that a protein has been detected. Players tag the image using a list of twenty-nine options (see right side of above image) that include nucleus, cytoplasm and periphery. When enough players reach a consensus on a single image, it is marked as “solved” and passed on to the scientists at the HPA. As Emma Lundberg, the director of the HPA’s Subcellular Atlas explains: “Humans are, by evolution, very good at quickly recognizing patterns. This is what we exploit in the game” [reference Better Research Through Video Games (The New Yorker 2016), by Simon Parkin].

Although scientific papers have yet to be published citing player contributions, however, the simple fact that such a possibility exists is very inspiring. Once papers are published it’ll be interesting to see how and if the real-world accomplishments of Project Discovery make their way back into the game via the Sisters of EVE, so that players can celebrate the lasting consequences of their work.

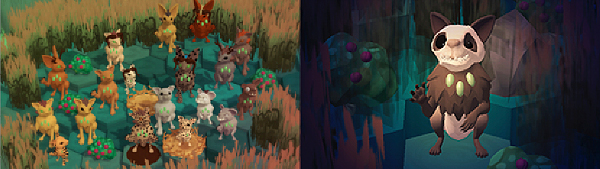

The subject of evolution in Niche, by Team Niche, predictably leads to many deaths—but such is life!

After Atilla’s presentation of Project Discovery the topic of death and consequence continued on a scientific bent with Niche: A Genetics Survival Game, presented by Zurich-based developer Philomena Schwab. Niche is a digital board game about genetics, heredity and evolution, and is currently on Steam Early Access. Players must try to prevent an animal tribe from going extinct, which is a challenge that implies that death happens…a lot.

Philomena was asked a question by Pippin about the character stylization—why the characters look so cute despite the serious topic of the game? Philomena responded by explaining that death is something that happens to every living creature, no matter how cute. She described once demoing to a young girl who was accompanied by her mother. The girl and mother cooed when a cute creature was born only to see it instantly killed by a predator. The mother was shocked while the girl shrugged and continued playing. It seems that are generally overprotective and don't give children credit that they can cope with such subject matter. It’s interesting to compare the emotional responses of players between Niche and games like That Dragon, Cancer, and A Series of Gunshots— a result of Niche’s deliberate objectivity.

With a large cast of characters, players of Niche, by Team Niche, self appoint “hero” characters based on gameplay events.

Philomena went on to explain that some emotional attachment does, in fact, exist since it’s natural for players to dislike characters that decimate a population with a bad genetic trait (sometimes going as far as using them to bait predators!) or find affection towards hero characters that save the day—even if they have the appearance of an ugly runt (above right). The short life cycle for each character, however, means that emotional bonds cannot last long.

Niche, by Team Niche, features an educational user-interface that illustrates the passing-on of genetic traits with appropriately simple icons.

The lasting consequence of playing Niche is the game’s educational value. Similarly to That Dragon, Cancer presented by Josh, Niche encourages players of all ages to speak objectively about death and, perhaps, developer a stronger acceptance through increased awareness. When all the creatures have died the player is presented with an appropriately matter of fact message—“Game Over. Your species has gone extinct”—and must choose to ‘Quit Game’ or go ‘Back to Main Menu.’

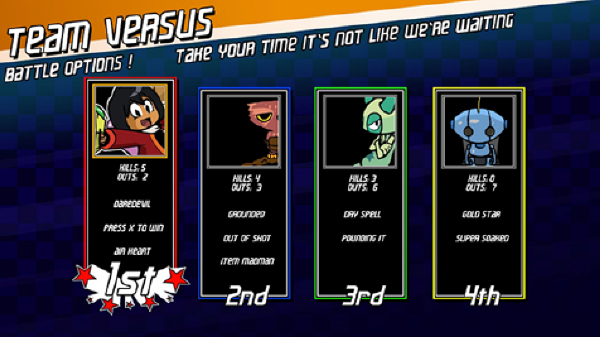

By comparison, the objective perception of death and consequence in Niche becomes entirely nonchalant in Splash Blast Panic, presented by Elias Farhan and developed by Team KwaKwa. Death in Splash Blast Panic is the kind that video game players are most familiar with—where dying or a game over state is equivalent to losing a point in a sports match. So, although death occurs constantly, the emotions experienced by players are more akin to a basketball or soccer player’s feelings of failure after a tactical mistake.

Instead of traditional firing weapons, Splash Blast Panic, features water pistols—due to the theme of “unconventional weapons” in the Ludum Dare 32 game jam, when the game was first conceived. Characters can be shot, stomped, blasted, attacked with super moves, or they can accidently kill themselves. Players talk in terms of: “I killed you” and “you killed me.” The underlying brutality of the game led Pippin to ask Elias why water pistols were chosen for the game’s weapons. Elias replied that water pistols make Splash Blast Panic’s multiplayer gameplay children friendly—which is curious since the game is more aggressive than many other games in the same genre. It’s evidence that the “skinning” of a game makes a huge difference to how its gameplay is perceived.

Death in Splash Blast Panic, by Team KwaKwa, is designed to be as un-frustrating as possible—hence the reason why players respawn on fluffy white clouds.

The intended experience of death in Splash Blast Panic depends on the situation. Successful players should feel satisfaction, power, and schadenfreude (pleasure at others misfortune). Losers should feel anger towards the victor and wish to learn from their failings. However, Elias and the development team learned that certain design choices made the game too frustrating for players—namely concerning the visualization of kills. The original user-interface displayed how many times each player had died as a negative value, which many players found disheartening. Elias explained that the user-interface is now reduced to only show who is in the lead without indicating the actual score per player. Where games presented earlier in the evening were designed to confront players with death, the sports-like concept Splash Blast Panic avoids pointing a derogatory finger at the losers and, instead, focuses on victories.

Splash Blast Panic, by Team KwaKwa, features an end screen that pampers to the players’ ego by excluding negative values for each time a player died during the multiplayer match.

Pampering of player egos is evident in other areas of the game’s design. For instance, deaths always happens off-screen—Super Smash Bros.-style—and respawning players fly-in on soft white rain clouds and can influence gameplay remotely for a limited time. The end screen also avoids showing negative kills—instead displaying deaths as “Outs” using positive values.

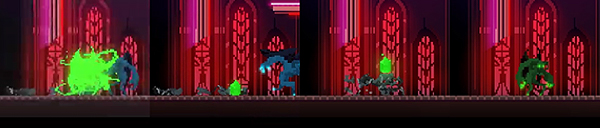

The playable gargoyles in Stonebond: The Gargoyle's Domain are designed to respawn as quickly as possible to maintain continuous gameplay.

The sports-like concept of death continued to David Javet’s presentation of Stonebond: The Gargoyle's Domain—a multiplayer gothic-themed combat game in which 4-players must form fragile bonds with each other. As with Niche, and Splash Blast Panic, death in Stonebond occurs a lot and is designed to be overcome as quickly as possible—a temporary nuisance—in contrast to games like Pippin’s, A Series of Gunshots. It’s for this reason, in part, that the characters are non-human gargoyles that have a very fast respawn time.

Stonebond is a 4-player “couch” game, which means that all four players must play together on one display. David explained that killing (or shattering) the opponents is the main gameplay action but it it not the goal. Victory comes from cooperative, 2 versus 2 gameplay. When two gargoyles are shattered a bond appears between the two remaining players. The linked gargoyles are invincible, and unlinked gargoyles must break the link.

Pippin posed a question for David concerning the terminology of the game’s core game mechanics—suggesting that the word “bond” has marriage-like connotations. David agreed and explained that the link between players was visually and audibly designed to be a fragile element that shatters—like the playable gargoyles—whenever it the bond is broken. Curiously, it often occurs during gameplay that cooperating players will hit each other in real-life when one of them misbehaves in-game.

The lasting consequences of death to players in Stonebond are shared with Splash Blast Panic: empowerment for victors, an invitation to take risks and experiment with alternative methods to create conflict.

From the diverse line-up of games presented during the evening it’s clear that death and consequence in video games is concept that various according to the context of each game. Sports-like games (Splash Blast Panic; and Stonebond: The Gargoyle's Domain) treat death as little more than a point lost and feature quick respawn times to avoid dwelling on player failures and maintain gameplay. We also learned that the choice of visual skinning has a big impact on the level of seriousness players will perceive (Jostle Parent, and Splash Blast Panic). Games that wish to represent the finality and emotional complexity surrounding death can do so using a series of gameplay vignettes, limit the number of deaths that occur, and avoid enabling quick replays to encourage contemplation (That Dragon, Cancer, and A Series of Gunshots). Project Discovery, and Niche: A Genetics Survival Game showed us that games can even have an educational and preventative effect on death in the real-world.In conclusion: death in video games is significantly more nuanced and affecting than we're usually led to think.

Thank-you to the Game Developers Suisse Romande meet-up, the Swiss Arts Council, Pro Helvetia, and the Swiss Game Developers Association (SGDA) for making the event happen.

---

Chris Solarski is an artist-game designer and author of the seminal book, Drawing Basics and Video Game Art: Classic to Cutting-Edge Art Techniques for Winning Game Design (Watson-Guptill 2012), which has been translated into Japanese and Korean. Chris’ professional background—which mixes game art development at Sony Computer Entertainment and fine art figurative painting—has led him to lecture on emotions and storytelling in video games at international events including the Smithsonian Museum's landmark The Art of Video Games exhibition, SXSW, Game Developers Conference and FMX. Chris’ personal projects at Solarski Studio continue to explore the intersections between video games, classical art and film to develop new forms of player interaction and emotionally-rich experiences in games.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like