Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Why difficulty is harder to design when you're oblivious to your own work.

This article originally appeared on www.skytyrannosaur.com.

This past week saw the launch of a game called Mega Man Unlimited. As the name hints, it’s a fan game based on the Mega Man franchise, and one that’s been in the works for over half a decade. It's an incredibly impressive project: it’s attractive, it’s clever, and it positively nails the classic Mega Man feel. For a small team spearheaded by a single person, it’s nothing short of a beautiful achievement, and it’s something I have nothing but admiration for.

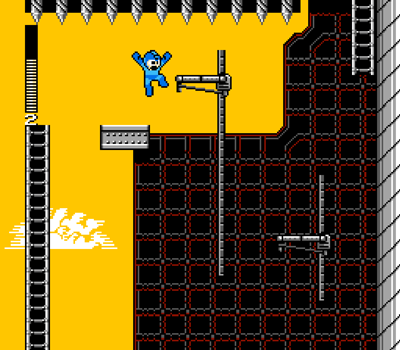

The only thing I can’t get behind is the difficulty. The game is simply too spiteful; its enemies do too much damage, its instant-death spikes and bottomless pits are too numerous, and its checkpoints are too far apart, ensuring that when you screw up – and you will, often – you’ll have to slog back through the same huge, deadly stretches of terrain just to get another shot at doing things right. The game is cruel, even by Mega Man standards, and it drags the entire experience down.

And I'd wager that this was completely invisible to the game's designer.

mmUnlimitedSpikes

Everything is better with instant-kill spike ceilings.This is a scary thought. As a designer, it’s terrifying to know that I will never, ever play the same version of my games as everyone else will. When I play Blowfish Meets Meteor, I don’t see a diver scouring an underwater cityscape for his lost mermaid daughters; I see hitboxes, all green and pink and blue and rigid, and I see the formulas behind the physics that make them move. I don’t hear the music; in its place, I feel a constant paranoia that it will suddenly stop, or that there will be a gap where it’s supposed to loop, or that a sound effect will trigger improperly. Above all, I don’t feel difficulty; I’m too intimately familiar with the bones and guts and impulses behind this thing. When you can accurately predict – or premediate, even -- the behavior of every single aspect of a game down to a single pixel, be it the player, the enemies, or the environment, there’s no mystery, and without mystery, there’s no error.

When you see a game in this light, everything feels too easy. Boss patterns become child’s play to recognize: who needs a fancy windup animation to warn them that an attack is coming when you've internalized the exact time interval that precedes it? Levels become a cinch to navigate: even the most obtuse, gnarled maze feels like a linear path when you not only know where the exit is, but actively influenced its position. And your own character’s mechanics are the easiest thing of all to wrangle: spending hours or days fine-tuning the frames and numbers behind every motion, maneuver, and attack gives you a sixth-sense about how to best handle things when it’s finally time to pick up the controller and play the damn thing.

As a designer, I know, somewhere up in the more logically-wired part of my brain, that I want my creations to be fun and balanced and fair. I want the difficulty to be tuned just right. To me, that means being friendly and accommodating up-front, showing the player the ropes in a controlled way, and gradually making things more difficult to push them to get better and more comfortable with the game itself. To that end, I’m constantly fine-tuning both the levels and the base mechanics to try and hit that perfectly-balanced mark. I view this as a good thing, and an incredibly important thing. Designers should aspire for balance, and doing so requires constant tweaking and testing.

But then your sixth-sense interferes.

Blowfish Meets Meteor Debug

Blowfish Meets Meteor bares its hitboxes.If you already know everything there is to know about a game, that makes you a master of playing it. And when you’ve mastered something, it feels easy. Too easy. And so, in pursuit of proper balance, you make it harder.

In a weird way, it feels like the responsible thing to do.

I’ve been guilty of this a lot with Blowfish Meets Meteor. I want so badly for the game to be clever and balanced and challenging-yet-fair that I’ll make things incrementally more difficult because it’s what feels right to me. From this bizarre perch I’m sitting on, “devious” simply looks “clever.” “Instant death” looks more like “polite punch in the arm.” I flirt with a lot of things that I objectively recognize are bad – things like puzzle rooms that require trial-and-error to avoid instant Game Overs, or traps that kill the player before they’ve even had a chance to get their bearings. I know these are horrible, lazy design crutches. But from up here, with this skewed sense of understanding of my own creation, they look amazing.

There’s this level in Blowfish Meets Meteor called “Piranha Peril.” Regardless of its actual merit, it is and always will be one of my favorite levels in the game. It was quite possibly the first puzzle-style level I created for this project; in a game about rapid-fire explosions and stupidly-big boss battles, making a level that focused on slowing things down and asking the player to think critically felt incredibly refreshing at the time.

The goal of the level is simple: there are a bunch of mermaids, and a bunch of mermaid-eating piranhas. The mermaids need to navigate to the bottom of the screen, where your underwater dome-house is. You, in the role of their deep-sea-diver father, have a meteor, which bounces around and destroys blocks (but, critically, not piranhas), and a bunch of TNT, which can be placed anywhere on the screen and will destroy pretty much anything. Go.

Blowfish Meet's Meteor's Piranha Peril

Piranha Peril, Mk. IThe mermaids move in a predictable pattern, walking left or right along solid ground until they hit a wall, which causes them to turn, or a piranha, which immediately devours them in a shower of blood and whatever the mermaid equivalent of veal is. If we take the game’s mechanics as canon and gospel truth, they’re simply not very smart.

Your options here are to break them out with the Meteor – which is possible, but not very fun – or to accrue TNT, and use it to destroy the terrain and/or piranhas impeding their progress. You get TNT by destroying blocks in rapid succession, and since there are only a limited number of blocks in your immediate vicinity, that means you’ve only got a few pieces of TNT to throw around, and you’d better use it carefully.

The first version of this level was terrible in a way that only a designer could love. Each of the two mermaids started the level by walking directly into the piranhas on their tier; players had a matter of seconds to start the level and flawlessly perform the exact right set of actions to liberate them or face a Game Over. When I asked friends to playtest it for me, most of them immediately lost, and their first response was often to ask “what killed them.” It was difficult in all the wrong ways, punishing players for not having superhuman reflexes or advance knowledge of the level and its hazards.

bmmPiranhaChomp

Chomp.The weird thing is, it took a while for that to sink in. When I watched people play the level, I didn’t think “unfair;” I thought “devious.” I didn’t think “trial-and-error;” I thought “clever puzzle.” I didn’t see “Game Over screen;” I saw a goofy, entertaining animation of a piranha chomping up a mermaid. Even when people outright told me that the level was frustrating, it was hard for me to accept it; I chalked it up to them being inexperienced with the game, or poor sports who needed things spoon-fed to them.

What if listening to them was the wrong thing? And what if, in doing so, I made the level so easy that it removed the puzzle? What if people blazed through it so quickly, so painlessly, that they never got to see that wonderful, clever brain-teaser that I spent so long bringing to life? To me, the level felt perfect, and messing with perfection was a tough sell.

It’s been nearly a year since I originally posted that first screenshot of Piranha Peril. It took until maybe a month ago for me to consider changing the level, and even then, I’m not sure what exactly triggered it; maybe that was simply the amount of time it took for me to distance myself from the original creation enough to be objective about it. Perhaps creating dozens of new levels, or playing the game from start to finish in its currently near-complete state, helped give me perspective. Or maybe I just became more critical of myself, or learned to listen more. Whatever the reason, today’s Piranha Peril is a much less masochistic affair. The instant-kills are gone; there are now blocks preventing the mermaids from walking straight into the piranhas, giving the player as much time as they need to initially process the level and figure out how to handle things. These new piranhas are all stationary, giving players one less variable to contend with. And the blowfish, who gives the player a useful power-up, has been moved to the center of the screen, where it’s much easier to utilize.

Blowfish Meets Meteor's Updated Piranha Peril

Piranha Peril Mk. III hope these things make a difference, and I hope they make the right one, but ultimately, I'll never know. I can solicit feedback from people, but I can never experience what they do. My understanding of my own work is and always will be secondhand.

So when I play games like Mega Man Unlimited – games that ooze creativity and talent and passion but feel slightly spiteful, all the same – I understand. Difficulty is a fleeting, fickle thing, especially if you’re the one in charge of it. When I play someone else’s game, difficulty issues feel immediately obvious, but with my own, they hide away, beady eyes in the shadows, for months or even years. Ironically, knowing more about a design means that, in some ways, you’ll always know less; no matter how long you spend creating something, you’ll never know as much as the newcomer who just experienced it for the first time. That’s been an incredibly difficult lesson to accept and digest, but doing so has been and will always be one of the most important learning experiences of my game design career.

The original article is up on the Sky Tyrannosaur blog. Join us on Facebook and Twitter as we attempt to craft a mobile game that provides the perfect challenge, all the time, for everyone.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like