Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

15 years ago this week, Ion Storm Austin released its seminal first-person cyberpunk game Deus Ex. Gamasutra spoke to some of its lead creators to learn more about how they developed it -- and what it did to them.

Fifteen years ago this week, Ion Storm Austin released its debut game Deus Ex.

The first-person cyberpunk game would go on to garner long-standing critical acclaim, become a high-water mark in the careers of game makers like Warren Spector and Harvey Smith, inspire a generation of developers, and cement the "immersive sim" genre of game design. (Alongside Looking Glass' System Shock series and later Ion Storm Austin release Thief: Deadly Shadows.)

But in the weeks following the game's launch, lead programmer and assistant director Chris Norden tells me that most of the developers at Ion Storm Austin had no clue that the game would be anything other than a well-received summer release.

"We didn't know what was going to happen," Norden, who now works for Sony in Japan, tells me over Skype. "The game didn't really get famous until a considerable amount of time had passed. At first, it was like, 'Oh yeah, this game is cool. The reviews are good. Okay. Cool.' It didn't become a real hit until many years later. So we all had no idea what was coming."

Looking back, it seems like a foregone conclusion that Ion Storm Austin's efforts would spawn a franchise and influence game designers around the industry, who went on to work on big-budget projects like BioShock and Fallout 3, as well as more intimate games like Neon Struct and Catacomb Kids. (It's all charted out in Rock Paper Shotgun's "Deus Ex Made Me" article series.)

Now, 15 years on, it seems appropriate to reflect back on the foundation of Ion Storm Austin and what it was like to work on its first and arguably most significant game. In a series of conversations conducted separately with project director Warren Spector, lead programmer and assistant director Chris Norden, composer Alexander Brandon and lead writer Sheldon Pacotti, we seek to shed some light on how this seminal game was developed, how it reflected the identities of its creators and how it affected the course of their careers.

Excerpts from those conversations are published below for your edification and enjoyment.

Warren Spector: There's no question the development of Deus Ex was a high point for me. The team was like a dysfunctional family at times, but their commitment to the project and our mission was complete. People worked very, very hard to deliver on the promise and potential, that's for sure!

There was a very strong sense that we were doing something special... unique. That kind of opportunity - to make the game of your dreams with no creative interference - comes up very rarely in life, and I think everyone, not just me, knew that and, as a result, really swung for the fences.

Sheldon Pacotti: Deus Ex was total immersion for me. I lived and breathed Deus Ex for a year, seven days a week, fourteen hours a day. I was just that excited by the potential of the game. The only comparison I could make is to writing a novel, where you completely lose yourself in a fictional world until it becomes indistinguishable from reality.

At the time, few people expected video games to represent reality or tell a story you actually believed in, so I was thrilled to find a team that was trying to make that happen. But I had no idea if fans would "get it." The most gratifying thing for me is the number of players, continuing up to today, who -- like good players in a paper role-playing game -- have stepped into the fiction and abandoned themselves to it. A collective hallucination.

Alexander Brandon: Deus Ex is the game I hear the most about. I'm proud of everything I've worked on. Unreal pushed boundaries of level design and fantasy world exploration in the context of an FPS. Unreal Tournament honed multiplayer combat. But Deus Ex blew the doors off genres, and at the time, hardly anyone had done that.

The time that I spent on it was pretty incredible. And I hardly made any revisions to anything I did. I'd certainly change that in hindsight, but at the time what we did just worked.

Chris Norden: At the time, we had no idea what it was or what it would turn into. We really had no idea. We hoped it would be a success, at least critically, and it kinda turned into something...big.

A partial Deus Ex development team photograph from 15 years ago, provided by Chris Norden

I've been at Sony for almost 10 years now, and I've been a very public face for developer support, and now Morpheus; I give a lot of the developer talks about Morpheus. And I still get people coming up to me today saying hey...weren't you that guy that worked on Deus Ex?

We knew the type of game we wanted to make: something that had real choices, that didn't just have A-B conversation trees where none of the choices really mattered. We wanted it to be interactive, we wanted it to be fun, we wanted it to have pretty good tech, and we wanted to have a strong story.

I think we were in between for about six months after Looking Glass shut down. We were basically jobless for like six months, and we were doing pitches and talking to publishers, and I think it took about six months total for us to get Ion Storm onboard so they'd start funding us to start and get staffed up.

Spector: Basically, Looking Glass Austin shut down because Looking Glass as a whole was in pretty dire financial straits. The LG Austin projects couldn't move forward until and unless I could find external funding for them and, despite the efforts I made, that just wasn't happening. I talked to the folks in Cambridge and we all agreed that it made no sense to jeopardize the larger organization trying to keep a satellite office open. I was pretty confident I could find another deal, so we shut down.

Even though I was part of the decision, it was still pretty gut-wrenching when I left the empty office for the last time, I can tell you.

As far as Ion Storm Austin goes, it took some time, but I wasn't ever too worried. The core of the team was willing to wait while I found another deal. I kind of knew what I wanted to make -- based on thoughts I wrote up for Game Developer magazine about what direction RPGs could take.

Ultimately, I came close to signing a deal to make an RPG for a major publisher, based on an existing IP, but before I signed, John Romero called me and convinced me to sign on with Ion Storm, to create an Austin office for them, and to make the game of my dreams, which turned into Deus Ex.

Norden: So when we went around to pitch our games we hear about this company that Romero started, called Ion Storm. They're in Dallas, and they've got this massive amount of money and they're hiring up all these people to do all this cool stuff, and they've got this...you know, kind of now what you'd call a critical attitude, this whole "fuck you, we'll do what we want" attitude.

And you know, we didn't really buy into that whole mentality, but we knew they were good and smart guys, and we knew what they wanted to do, and it turned out to be a really good fit for us. Especially because we got to keep our office in Austin, because none of us were going to move to Dallas.

Spector: Okay, there were some frustrating arguments with people - not John!... with people who thought I should "just make a shooter." But I was able to fend them off and make the weird genre mash-up we ended up making.

Yeah, that game-of-your-dreams stuff was pretty good.

Norden: Warren had a bunch of awesome ideas, and we kind of put them together and they kind of formed the early framework for what Deus Ex became: this freedom-of-choice action-RPG with a lot of really awesome writing, which Sheldon did, and pretty cool tech at the time. Just cool open decisions, you know? Where you could do whatever you wanted, and approach problems in any way you wanted to.

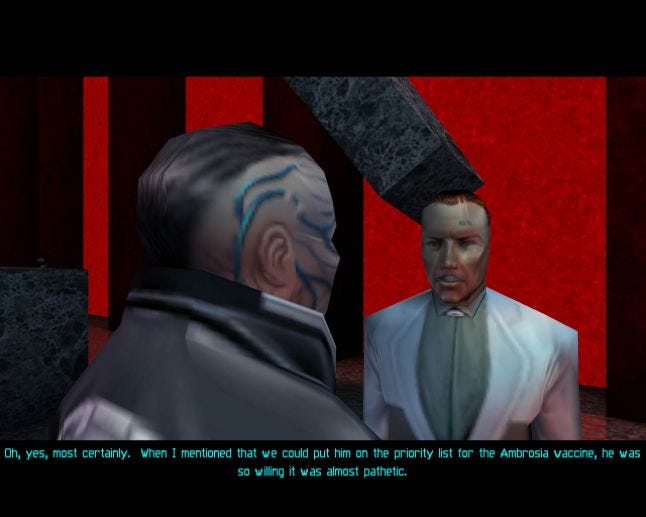

Pacotti: I have a vivid memory of a design review during the summer of 1999, a routine event for the rest of the team, but for me it was a terrifying moment since I was a new, provisional employee, and since some of my early writing was in the game.

The developer playing the game (Chris Norden) behaved like a typical jerk player, killing friend and foe alike. This prompted Paul Denton, the player's colleague and brother, to say something like, "You jackass!"

Deus Ex demos running at E3 in 2000

I cringed, thinking everyone in the room must be thinking the writing was juvenile. After a few chuckles, though, everyone grasped that the game had reacted to Chris' playstyle. The only verbalization of that was Chris murmuring something like, "Wow, that's cool," before plunging ahead with the playthrough. But for me, that was a key moment where I realized that the winding pathways of logic I was writing were going to be appreciated--that I was on the right wavelength.

Norden: Oh yeah, I forgot about that! Everybody would respond to everything, basically. That was pretty cool. [Sheldon] is probably the most under-appreciated member of the team, I think. He pushed us so hard on stuff he wanted to do. I'm sure I said no to him a lot, because it was ridiculously hard, but we figured out ways to do it. We had a whole conversation editor and system, and you could do some really cool stuff in there that hadn't really been done before, with the storytelling side of things. Sheldon drove us a lot, to do that stuff.

Spector: It was also pretty cool seeing Sheldon Pacotti flesh out the story with a level of intelligence that still blows me away.

Norden: He was pretty much solely responsible for all of the story stuff; he wrote all the dialog, for the most part. He told us what the conversation system needed to be able to do. He designed the cinematics system. We implemented everything, and it turned out awesome. We gave him a lot of tools to tell the story he wanted to tell, and it turned out so good. He rocked that stuff so hard. Looking back on it, it's still powerful. The story is really powerful, and it still gives me goosebumps in places when I watch some of it.

Brandon: I think a lot of the voice acting is cheesy, but it still works somehow. It lends the game a personality, not in a realistic way that people can actually relate to, but that makes the characters more memorable. What's communicated in those voices instantly gives you an idea of who these characters are, I think.

I'm thinking specifically of the voices of J.C., Paul, Gunther and Anna Navarre. Gunther and Anna came across very clearly as people you shouldn't be fond of. You get into Invisible War, and there's a lot less of that; I hate to say it, but I think it's because one of our goals on that project was to hire better actors and do better voice acting. [laughs]

Which we did! But it kinda distilled it too much, oddly. Wiped out a lot of the character.

Norden: One of the things that I did which I don't think anybody had done at the time, was...because we had so much dialogue, we wanted lip-syncing with the characters. But there was no way we were going to have an artist go and do all that by hand, because there was just too much dialogue. Also, all the different languages and localizations; it would just be impossible. An artist would die if he had to do that much lip-syncing work.

So I played around with the math, and basically did some really simple audio analysis using a fast Fourier transform to analyze the audio in real time, then match it to lip shapes, basically. Match it to phonemes.

I know Valve had done what's known as envelope following for some of the multiplayer in Half-Life, but that was just a very simple thing; you open the mouth wider if the sound is louder. It was super-simple, and I didn't think it was very good. I wanted to do something more, so I broke down -- for the English language, at least, I didn't do all the other languages -- I broke down what's called phonemes.

Basic sounds in speech, like "ah" or "ooh" or whatever, they all have frequency fingerprints, basically. Even with the low CPU power at our disposal, I could do a really low-resolution fast Fourier transform to analyze the speech as it was being output to the sound card, chop it up and try to match it with phonemes. Then I could use that to send hints to the animation system to move the lips.

So I had the artists animate the face bones, of which we only had like two, I think -- it was super low-poly -- and I had 'em go with eight phonemes to animate face poses for. Except, they'd do it on the base pose and I'd blend in the animations on the face in real time based on what the audio does.

So I created this initial test level which was basically just a big-ass head in a room. I fed it a bunch of random lines, and it was awesome: it matched up almost perfectly, and it was really convincing, and it was all done in real time, which I think had never been done before at that time.

I think I still have that test room. It runs a little too fast and doesn't work as good on modern machines, but I remember showing the initial test map to Warren and saying, "What do you think?" And he was like, "Holy crap, that's amazing."

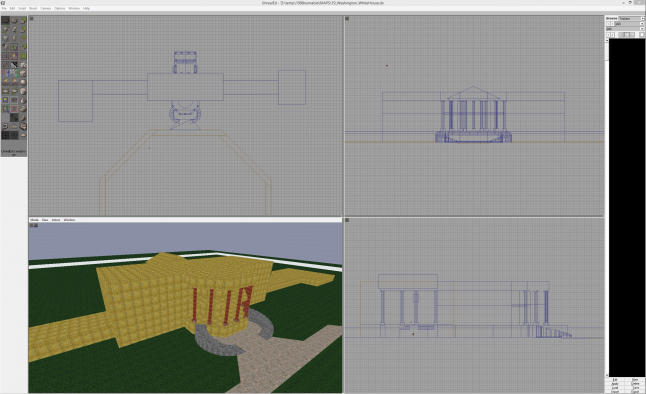

Norden couldn't turn up an image of the remembered "giant head in a room" test level in time for this feature, but he did provide these editor shots of one of the cut Deus Ex levels: the White House

So word got up to Dallas, and one of the people in charge there -- I won't say who -- came down to Austin and basically demanded that I give him the tech for his game. I literally got into a screaming match with him, in the hallway; I was like "No, we developed this here, for our game. I won't give this to you for you to ship first and take credit for it."

And he wouldn't drop it. He was like "No, you have to give it to me. I'm your boss; you will give it to me."

And I refused to. I was like "Nope, go ahead and fire me. I'm not giving you this tech."

And looking back, maybe it was kind of a dick move, because we all were the same company. But at the same time, I knew this guy's reputation, and I didn't want him stealing credit for something we developed in our office, for our game.

Brandon: There were smart people everywhere [at Ion Storm Austin]. One person in particular was a rocket scientist: Bob White. He had a Ph. D. in rocket physics or something like that, I think; he went to work at Los Alamos after leaving Ion Storm Austin. So we had a lot of people that were smart, and that's also what created a lot of friction.

If people didn't agree, it usually wasn't about something simple; it was about something very complex, something difficult to even explain or communicate. And that, by far, was the place that Ion needed to grow the most. We had people that were capable, who knew what they were doing. But in terms of resolving issues....I mean, Warren is a guy who, to this day, as far as I know, he doesn't like to have people upset with each other.

Spector: I realized that the team structure I'd set up was fatally flawed. I brought in a team of what I thought of as "Ultima guys" - traditional RPG designers. And I brought in a team of what I thought of as "Looking Glass guys" - immersive simulation designers. I thought I could manage the tension between the two groups and end up with the best of both worlds.

Man, was I wrong. What I ended up with was kind of a war, where I had to call one team Team A and the other Team 1, because neither team would be "B" or "2!" I eventually had to merge the two teams under one lead designer - Harvey Smith - who kind of fell into the Looking Glass mold. It all worked out okay in the end, but it was pretty stressful for a while!

Brandon: I had lunch with Warren not too long ago, and he's the first to say, "Boy, yeah, did we fuck a lot of shit up at Ion." He puts himself in that mix. It's great to hear him say that, because I know I made a lot of mistakes, and learned an awful lot.

The lessons I learned there were how to communicate, and how to foster good team dynamics in an in-house situation. When you're working full time with somebody, you need to learn how to express yourself in a proper, honest, succinct way. For most people -- I don't care if you're in the game industry or not -- that's not easy. You're not trained how to do that in school, really. You have to learn it on the job, through practice and experience.

From what I can recall, there was no continuously updated design doc for Deus Ex. If there was, I never saw it and I didn't get access to it. As a matter of the fact, for the original Deus Ex, since I came in near the tail end, I was mainly asked to do audio tasks to help ship the game.

A piece of concept music from Brandon, described as "a demo tune for Cliff Bleszinski, for a game after Unreal and Unreal Tournament" that would feature vampires. The piece is inspired by the trailer tune to Dark City, and after the post-Unreal project never happened it became the seed of the Deus Ex theme music.

So the only things I was really privy to were tales from the programming team about how frustrating it was to deal with the design team. Certain people in particular.

There were people there that didn't know how to say "Okay, I understand why you believe that. I don't believe that. I have to make this decision, because I'm the one in charge of this aspect of the game."

People had trouble with that! People couldn't just come out and say things like, "Well this is what I believe, and this is why things have to work this way." But, you know...Warren was a veteran at the time, but a lot of us were younger. So there was a lot of friction.

Spector: We had a bunch of knock-down drag-out fights, for sure. I've already talked about Design Team A and Design Team 1 - you can imagine what that interaction was like. But things also got hot, at times, between Harvey Smith, the lead designer, and Chris Norden, ace lead programmer and assistant director.

Harvey wanted the sun, the moon and the stars. Chris was the King of No. It was kind of his go-to response to any question or request. The funny thing - and I'm not sure he ever realized it - was that any time he said "no" I knew I was going to see whatever he'd said "No" to, usually within 24 hours.

Norden: I was the person who always said "No. No, no, no. We can't do that." You know? It was like, "The tech won't support it. We can't do that. You guys are full of shit, there's no way. Impossible."

I said "impossible" a lot. One of Warren's little jokes was that he would always ask for features, I would tell him it was impossible, and then...the next day, I would have it implemented. I'd spend time tweaking things, saying "well....maybe, if I do this, and I change this..." or whatever. And then I'd stay up and implement it, just to do it.

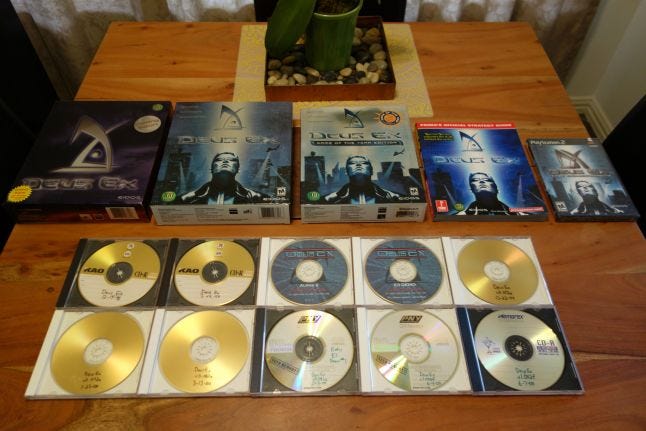

A collection of Deus Ex build discs, including E3 and alpha builds. The earliest is dated December 1998.

And then we'd try to put it in somehow, design gameplay for it; sometimes Warren would say "Oh well, I knew you were gonna do it, so I went ahead and designed this whole mission around it."

That was kind of cool... and kind of annoying at the same time.

Brandon: Chris [Norden] and I became, and still are, good friends. He introduced me to my wife! I met her while we were working on Deus Ex 1. She walked by the door of my office and I thought, "Wow. She must be married to some really good-looking dude that works here."

But no, she was Chris' high school buddy, and he introduced us. Then later on, he called me on an inter-office call, and when I picked up the phone I heard, "Got a present for ya!"

We'd all played Command and Conquer quite a bit, and he was jokingly imitating the Commando's line when you plant a stick of dynamite. Then he gave me her number -- I guess she'd asked him to -- and then it took off from there.

Definitely the most pleasant thing that happened, by far, during Deus Ex 1, was that experience. Meeting my wife, falling in love, and all of that. That was a big deal.

Norden: Even though we all fought a lot, we generally got along. We did lots of group dinners; there was a Mexican restaurant right across the street when we moved into our final office space, and they knew us by name because we were over there all the time having margaritas or whatever for happy hour. Just the level of camaraderie on the team was, I think, really good.

Of course, y'know, crunch sucks. No matter what industry you're in. And in the early days of the project, you don't really notice it as much, but when it started to become a real game with real deadlines and the publisher starts applying pressure....I was working a shitload. I mean, I slept under my desk a couple of times. We all pulled pretty crazy hours sometimes.

And that of course leads to tension, both at home and at work. So personally, I was having relationship issues, just because, you know, you're working all the time. You don't get to see your friends very often. Your wife or girlfriend, you just never get to see her. It causes problems, and then you get stress in your personal life, and then that stress comes back across into your work life. So it kind of cascades, and kind of builds upon itself.

That was always a problem, and everybody kinda had that. It's hard for spouses and significant others who don't work in that industry to understand why you're doing it. Because you don't do it just because you feel obligated to; you do it because you want to make the game awesome. "Oh, I've got this feature I want to put in, but I'm going to have to work late. But I don't care, fuck it! I'm gonna put it in, because it's so cool!"

And then you come in the next morning and the designers have this new tool they can use to make the levels even better, and it's totally worth it. Stuff like that, being able to add features the designers didn't know they wanted, was really, really awesome. That was one of the best parts of the work I did there

Spector: As far as crunch goes, there was plenty of that. I'm basically terrible about budgets and scheduling. It's amazing I ever get work!

I feel a little guilty about how hard I worked the DX team, but at the end of the day the hard work paid off. I think if you asked anyone on the team today what they remember of that time, they'd just remember the exhilarationof working on something special.

Brandon: Yeah, it all sums up for me as a net super-positive experience. Something I really wish everyone could have, in some way. It was unique, and fantastic.

You May Also Like